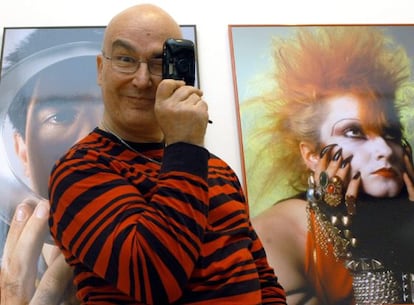

Pablo Pérez-Mínguez, the iconographer of 'la movida'

Photographer had gift of good timing but eventually left camera to one side

Photographer Pablo Pérez-Mínguez, who died last week at the age of 65, will be best remembered for his work during the decade that followed the death of General Francisco Franco, when Spain underwent a countercultural revolution known as la movida.

Largely self-taught, Pérez-Mínguez, who signed his work PP -- "pobre pero mítico" (poor but a legend) he liked to joke - described the movida as "one of the most important creative movements of the 20th century," and set out to capture on film the men and women behind it, including Oscar-winning film director Pedro Almodóvar and pop singer Alaska, besides a great many now forgotten, some of them dead.

Talking to EL PAÍS in 2006 when he was awarded the National Photography Prize, he downplayed his work in typical fashion. "My father would only take the camera out of its case on very special occasions. I remember thinking as a child that if I always had a camera with me, then everything would always be wonderful: and that's how it's been!"

He was always to be found in the right place at the right time, whether in the dressing room of the legendary Rock-Ola nightclub where Almodóvar used to sing, or in the art gallery run by Fernando Vijande. His work, all in glorious color, captures the energy and immediacy of a generation happily taking advantage of a period of unparalleled permissiveness after 40 years of crushing dictatorship.

In his mother's old apartment he made the space to set up a studio and organize parties to show off his work, attended by fellow photographers Alberto García-Alix and Ouka Lele, actor Antonio Banderas, and musicians Bernardo Bonezzi and Carlos Berlanga. But there was more to PPM than simply being the official snapshot archivist of the movida.

He had already been a professional photographer for a decade prior to being introduced to the scene by Javier Pérez-Grueso, a member of pop group Radio Futura. Pérez-Mínguez and designer Carlos Serrano, who had met studying agricultural engineering, were working for the pioneering photography magazine Nueva lente (1971-1983), a publication primarily devoted to showcasing and discussing the work of Spanish photographers. As Serrano said last week following the death of Pérez-Mínguez, most of the photographers featured in its pages had turned against the documentary style and typically radical politics of the generation of photographers that came before them.

He captured the energy of a period of unparalleled permisiveness

Bored with Spain, in the late 1970s, Pérez-Mínguez and Serrano closed down their magazine, and had planned to move to France, but no sooner had the former landed in the French capital than his luggage, and all his cameras and photographic equipment were stolen. The pair returned, and started up the magazine again. But events were changing fast, and Pérez-Mínguez found himself drawn ever closer to the movida's spirit of rebellion.

From the mid-1980s, as the movida began to lose steam, and many of its main figures had either begun making careers for themselves, had become lost in a haze of drugs, or simply settled down, Pérez-Mínguez divided his time between work for the record industry and a series based on subverting the Spanish tradition of religious paintings, often using the slogan "No holds barred," or "Total anachronism."

His friends say that during his final years, he spent more and more time writing, or as he said: "fighting to stuff more into the time I have, given the impossibility of extending it." Pérez-Mínguez largely abandoned his archive of some 200,000 images, barely taking any more photographs.

"By the end of the 1990s I became the ''unsinkable photographer.' Then I became a 'legend.' Finally, in 2001, 'I died'," he said in 2006 after winning the National Photography Prize, referring to a newly published dictionary of photography wherein he was indeed described as having expired in 2001.

Eleven years later, when he finally succumbed to illness, he played down the event, in typical fashion.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.