The letters from Mexico that reveal interrupted Republican lives

Unpublished material made available to EL PAÍS tells the story of the thousands of families forced into exile from Spain as a result of the Civil War

"With Spain present in my memories / with Mexico present in my hopes.” So wrote the poet Pedro Garfias aboard the steamer Sinaia, one of the first ships to bring thousands of Republican refugees to the port of Veracruz in June 1939, following the Spanish Civil War. But there were still hundreds of thousands of exiles left behind, most of whom were trapped inside French concentration camps.

In anticipation of an imminent end to the Spanish conflict, the Mexican government of General Lázaro Cárdenas had launched what is probably the greatest operation of international solidarity ever conducted. Mexico was willing to provide a home, food and work to people who could never again find peace or forgiveness in Franco’s Spain because of their Republican past.

In the darkness of the overcrowded, disease-ridden French barracks, hungry and desolate Spaniards who had lost their families, friends, jobs and stations in life saw Mexico as a bright and alluring land of dreams.

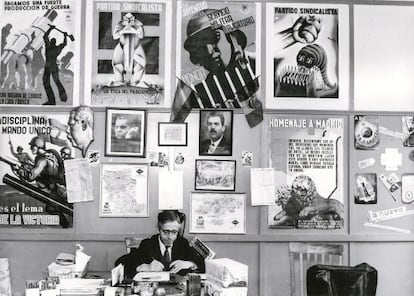

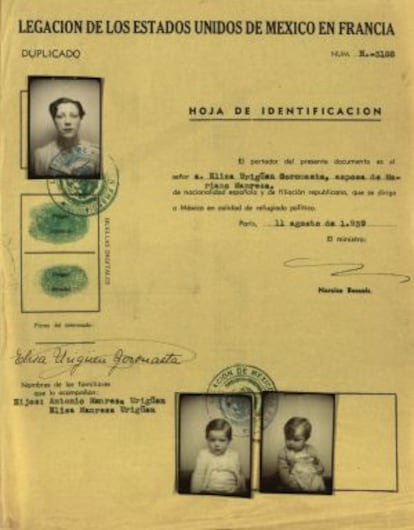

The voices and entreaties of those thousands of defeated people who just wanted to escape from their nightmare were recorded in the letters they sent between 1939 and 1940 to the Mexican Embassy in Paris requesting asylum. This unpublished material, which is kept inside the Diplomatic Historical Archive of the Mexican Foreign Relations Secretariat, was recently made available to EL PAÍS. Its contents reveal a collective tale of pride and despair, of tenderness and courage, on the part of men and women from all walks of life.

Hungry and desolate Spaniards saw Mexico as a bright land of dreams

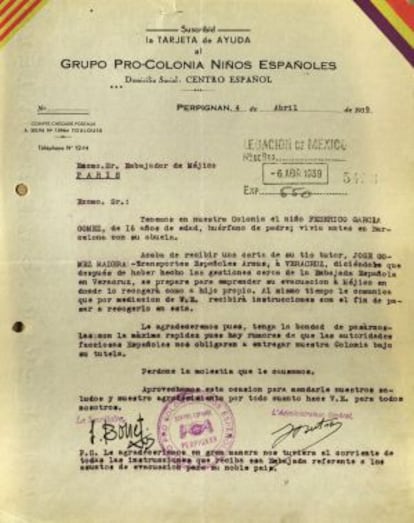

There are over 7,000 letters, representing many more interrupted lives, written with pens or pencils on all sorts of paper by the people who, in the winter of 1939, had crossed the border into France “on foot, with no fortune but with clean hands,” in the words of the refugee Fernando Pintado, who wrote that phrase on February 14 near Perpignan. In many of the missives, the author also added the names of his family members, workmates, comrades-in-arms and fellow barrack dwellers.

Most of these border transients ended up in internment camps — that was their official name — in southern France, under the watchful eye of French gendarmes and Senegalese soldiers. Their letters offer testimony of how tough life was on the inside. José Pomés, a Barcelona writer for Diario Gráfico and La Noche, wrote the following from the Bram camp on June 12, 1939: “I find myself in the most deplorable state, without clothes, without health, without French money... before long it will have been three months that I’ve been lying on a pile of straw without so much as a blanket to cover myself with.”

“Mr Ambassador: A thousand pardons for writing with a pencil. [...] We only have enough ink for the envelope, due to the fact that we have no French currency and they reject our Spanish money,” wrote Carlos Sala Franqueza, 48, from the camp at Champs du Bigné.

Manuel Guiú Macía, who requested “voluntary enlistment in the Mexican army or its legion,” wrote from inside Barrack 27 at the Septfonds camp: “The days here go by slow, eternal, and the dawn takes so long to break over this darkness!!!”

Three Republican militiamen interned at the same camp signed the following shining example of literary humility on July 2, 1939: “Never doubting that the voices and the pleas of these stateless petitioners will be addressed with the justice that our case requires. We are peasants by trade.”

To their dismal material conditions, the interned exiles had to add utterly unfavorable political circumstances that only the principled tenacity of the Mexican government and the skills of its diplomatic corps were able to overcome.

One of the documents that had been gathering dust in the archives is the following message sent on January 27, 1939 by the Mexican ambassador to Paris, Narciso Bassols, to Mexican President Cárdenas: “France policy to remain unwavering. Stop. Relations tells me we may not receive former combatants or political refugees. Stop. Understand problems, just permit me to ask you for Mexico to maintain its universally known offer to open doors to Spanish Republicans. Stop. I think that, as they are people with well-defined political affiliations, we are under the obligation to accept them.”

There were added difficulties, such as the rivalry between various Spanish organizations competing to help the refugees, or the differing selection criteria used by Mexican authorities to grant asylum, to even the consideration of whether or not it was convenient to take men of military age out of Spain before the end of the war. Ambassador Bassols illustrated this last problem starkly in another telegram dated March 1, 1939: “Since Spanish fight has not ended useful workers cannot definitively go away weakening resistance. Stop. In general still not receiving quality requests save for elderly people and children. Stop. To this day vast majority [of letters are] from self-defeating people with no sense of social struggle and displaying petty selfishness. Stop.”

These are tales of pride and despair on the part of people from all walks of life

The exiles’ general sense of despair was soon heightened by another element of fear: the imminent recognition of Franco’s government by France and England and the ensuing deportations, as well as the breakout of World War II. All this is reflected in the missives of Republicans, who are aware that they will no longer be able to return to their country.

“My status as magistrate makes it unthinkable for me to return to Spain; the French police are breathing down my neck because of all the stay extensions I’ve requested,” wrote Juan del Hoyo in September 1939 from Bordeaux.

“I must tell you that my wife’s political activity in Spain [Maruja Lafuente, a 25-year-old from Gijón] was quite significant, as she held positions of top responsibility in the Communist Party of the Asturian Region, also she is sister to the heroine of the Asturias October Movement, Aída Lafuente, and it is for this reason that under no circumstance can I return to Spain,” explained Ramón Infante Varela from the Civilian-Asylum hospital in Montauban. Juan Ponsivell, of the Carpenter Brigade at the Barcarès camp, asserted that “there is nothing in my conduct during the war or before it that I should feel ashamed about, but I don’t want to return to the land that has been trampled by foreign fascism with the help of a few men who, like Count Julian, betrayed their country and murdered their brothers.”

The motives may have varied, but the urgency to flee to Mexico was always the same. The infantry captain Antonio Pascual Arnao, 34, explained on April 20, 1939 that “mainly because I am a freemason it is evident that my return to Spain is absolutely impossible without exposing myself to a certain and irreparable repression. […] We must keep in mind that Franco has sworn to exterminate the masons, something that he is carrying out with unusual cruelty.”

That same day, the mechanic José Puig Bosch wrote from the concentration camp at Argèles-sur-Mer: “I renounce returning to my homeland; according to news from my relatives, more than 100 books of mine were burned during a house search […] for the simple reason of being lifelong Republican-federals and having failed to baptize anyone for two generations.”

Other applicants alleged “moral incompatibility” with the Franco regime.

The international situation continued to worsen with the fall of Paris in June 1940, the German occupation of France and the creation of the Vichy regime, led by Marshal Pétain. The asylum drive by President Cárdenas became extraordinarily complicated. Mexico, a country with no resources and no navy, was dealing with another country under military occupation and limited sovereignty over the issue of a population of stateless exiles.

Besides that, war would soon spread to the Atlantic theater, making the ocean crossing nearly impossible. The evacuation of Spaniards was put on hold for months, as the letters show. Only the persuasiveness of the Mexican diplomat Luis I. Rodríguez enabled a relaunch of the refugee evacuation plan. In a memorable interview held on July 8, 1940 at Vichy, Rodríguez convinced Pétain to authorize the operation, though not before having to deal with questions such as the following: “Why this noble intention of yours that tends to favor undesirable people?” Or statements along the lines that Republicans had to face the fate “reserved to rats during times of great misery.”

Motives varied, but the urgency to flee to Mexico was always the same

But the verbal prowess of Luis I. Rodríguez prevailed, and following the agreement of August 22 of that year, Mexico agreed to take in all Spanish refugees in France and to cover part of their maintenance costs, which were mostly defrayed by Republican support groups. After the fall of the Spanish Republic, around 450,000 Spaniards fled to France. Two-thirds of them ended up going back to Spain. But from 1939 onwards, 20,000 found a new home in Mexico. That first year, 6,236 refugees were taken in, with just 1,746 making it to Mexico the following year. The letters prove that the number of applications far outstripped the number of people who finally saw their dream come true.

The missives were written mostly by men aged between 25 and 45, and who hailed from Catalonia, the Valencia region, Asturias, Andalusia and Madrid. They all followed the same structure: expressions of gratitude to Mexico, a list of anti-Fascist deeds and professional merits, a description of their future contribution to their host country, and the tale of their personal misfortunes.

Even though the exiles were mostly professionals and qualified technicians, many letters were written in a surprisingly literary style: “We desire no gift for our lives. We ask for warmth for our aspirations;” or “Mexico, liberal emblem of Hispanic America, on this day we offer you the promise of our sacrifice;” or “...who had to flee their land before the black reactionary ghost, which was backed by the military perjurers, sons of those merchants of the sword who, in the remote past, had no other occupation than theft, murder and mockery of your customs on their colonial adventures.”

Extreme necessity also led to a certain degree of wiliness on the part of some applicants who desperately wanted to emigrate. There were those who claimed to speak several languages, and a journalist from Madrid named Ezequiel Enderiz Olaverri, 49, who held that “I am currently working on a biography of Mexican President Mr Lázaro Cárdenas,” or the Seville lawyer Ricardo Calderón, 40, whose literary merits allegedly included “a poem entitled Sac…Nicte that could be of extraordinary interest to the Maya Indian.”

Extreme necessity led to a degree of wiliness on the part of some applicants

Meanwhile, the Socialist tinsmith from Madrid, Federico Antonio de la Huerta, a police officer during the war, alerted the ambassador in a letter sent from the Bram camp that “you were surprised in your good faith with the arrival of many high and mighty émigrés with no known profession; the concentration camps are where the real workers, revolutionary and honest, are to be found…”

Many of the refugees explained, sometimes through drawings and diagrams, how Mexico might make good use of their professional experience in industry, agriculture, the army, teaching, academia, the press, theater, and even in the business world. Some cases are touchingly comical. Vitaliano Gómez, writing from Barrack 44 at the Septfonds camp, proposed to Mexican authorities “the creation of a farm with 250 laying hens and 20 brood rabbits,” for which end he would require “a credit of 2,500 pesos to be paid back over four or five years.” Antonio Martínez, a farmer from Murcia, offered his assistance to improve the quality of peppers in the land of hot chilies, while Mariano Potó, from Barcelona, suggested that “it would be interesting to create a university chair to disseminate among Mexican intellectuals the synoptic conception of culture…”

But the letters mostly testify to the tragedies of thousands of broken lives. Carmen Planet explained her case thus: “...having lost my husband in Madrid on November 7, 1936 after enlisting as a volunteer when he was a retired military man, and having also lost a 17-year-old daughter, who went to fight as a volunteer and died on October 20, 1936 on the Sigüenza front, and of the three sons I have left, also volunteers, the 18-year-old is a war invalid and the 22-year-old, a lieutenant, is currently at the camp of Argelès-sur-Mer…”

The five sisters Pla Palleja, from Rubí (Barcelona), aged between 20 and 34 and interned at the Berck Plage camp, said they had 3,600 pesetas for the trip and “two wristwatches and one pocket watch, one large gold ring and two gold coins from Argentina.” Since these were their only belongings, and they feared not being able to afford the tickets, they begged the ambassador to “let us go to Mexico even if it’s in a corner of the ship and without food.” Antonio Paños Garrigues, a 36-year-old radio telegraph operator held at Bram, informed the ambassador that all his close relatives died “victims of aviation during the war” except for his brother Pedro, “who was executed by the Fascists in Málaga in 1937.”

An exile in Paris, Licesio Domínguez Lorenzo perhaps summed it up best when he said that “truly, it is very sad to have to hide as though one were a bad person, when my only crime is to have defended the SPANISH REPUBLIC.”

For decades, the Mexican chancellorship has preserved the cries for help of these thousands of Spaniards — tailors, waiters, teachers, military personnel, peasants, mechanics, actors, journalists, accountants, public workers, doctors, electricians, engineers, students… — who found a new home in Mexico. Today, they are finally being rescued, as Juan Rejano wrote, from the “steely crown of oblivion.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.