"We have no assurance of what they're going to eat in the coming months"

The crisis and terrorism have condemned the Sahrawis to a waiting game

There is an abundance of stars, sand and time in the Sahara desert, and a shortage of everything else.

"We're poor, do you understand? We have no land, no nothing. The only thing we have is the help we get from our Spanish brothers," says Nana Sidati, 22, with an intelligent gleam in her eye.

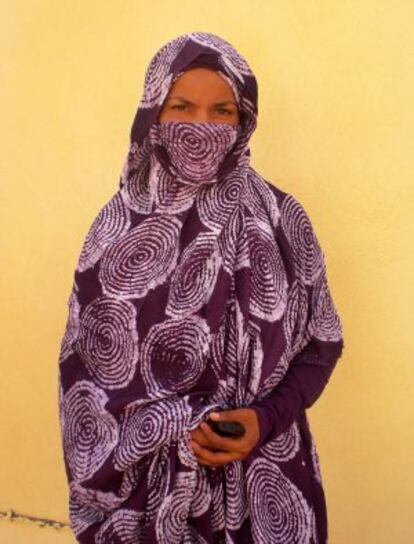

Nana is sitting on the curb, covered from head to foot in her purple malhfa, the traditional dress for Sahrawi women, despite the 45-degree heat. Her hands are clasped tight around the cellphone that her Spanish "father" has given her. He is one of the activists who traveled to the refugee camps of Tindouf, Algeria on August 7, in clear defiance of the Spanish government's call for repatriation of all aid workers in the area after one Italian and two Spanish volunteers were kidnapped there last year, being held until last month.

This young woman lives in one of the five Algerian wilayas, or camps, that house refugees from Western Sahara, the disputed territory that Morocco claims as its own but for which the Polisario Front wants independence. It is the only camp with electricity; none have running water. This particular wilaya is called February 27, a tribute to the anniversary of the creation of the self-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, or SADR. Nana's future extends no further than her own tent and the small adobe building that serves as the kitchen.

Five camps house refugees from the disputed Western Sahara territory

"I get up, I make tea, if it's my turn instead of my sister's, then I make lunch... From the house to the kitchen and from the kitchen to the house - that's life, and whatever you're doing today you'll be doing again tomorrow," she explains.

Nana's life is on hold, as are those of the other 165,000 Sahrawis who came to the Algerian hamada (a rocky desert with no dunes) in 1975, after the Moroccan occupation of the former Spanish colony. Since then, all they do is wait, a forgotten people living in a hostile, almost moon-like landscape, where everything is the same ochre color: the tents, the adobe houses, the earth and the summer sky, which is covered by a cloud of dust. Theirs is a festering conflict that is only getting worse - first the crisis, and now the terrorist threat in the area. The Sahrawis are drowning in the desert.

In Rabuni, the administrative capital of SADR and the place where the aid workers live, the warehouse kept by the United Nations World Food Program is a graveyard of empty containers and pallets, which only adds to the overall sense of abandonment. The food reserves contain enough barley and oil for a month. Everything else has run out.

"The situation is dramatic," warns the president of the Sahrawi Red Crescent, Bouhabini Yahia, as he walks inside the soulless building. "We have no assurance of what they're going to eat in the coming months." International aid has felt the pinch of the crisis. The money sent by the Spanish state (not counting regional aid programs and funding from non-profit groups) has been slashed by three million euros (it was 5.69 million euros in 2012). Spain is the Sahrawi people's main donor.

From the house to the kitchen and from the kitchen to the house - that's life"

But the food aid has not been covering the population's needs for several months now, if not years. The UN hands out 125,000 food rations a day. There is no official population census, but Algerian authorities talk about at least 165,000 people in the camps. The figures don't add up. The malnutrition rate for children under five is nearly 30 percent, according to the UNHCR.

"Moroccan terrorism is trying to annihilate us and isolate us, and it is trying to damage our relations with our friends in Spain," the president of SADR, Mohamed Abdelaziz, told the delegation of activists who traveled to Tindouf in early August.

The consequences of the Spanish evacuation of aid workers were immediate: one of the malnourished children in the care of Médicos del Mundo died during their 10-day absence. The handout of fresh food by the Basque non-profit Mundubat was delayed by 15 days. And the Spanish foster families who travel to the camps each year for the summer program might be afraid to go now.

Moichar Moulud, also 22, has just returned from Galicia, where he spent eight years studying, getting as far as finishing his secondary education. When he speaks in Spanish he reveals his knowledge of a number of curse words. The lack of opportunities for him and his contemporaries has driven them to a belligerent discourse. He says that he talks about it with his friends, who don't see any other way out of their predicament. He used to be a pacifist, he says. But now he has grown tired of waiting. "I can't see any other way out but war."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.