Plasenzuela's dirty secrets

For two decades this tiny rural community in Extremadura siphoned off millions of euros in state, regional, and EU funding based on non-existent projects

A goat has just given birth in a ramshackle shed. The animal's udders are still swollen, and it bellows: there is still another kid to come. Outside the shed, the sun is setting like golden oil boiling on this yellow, blinding hill in Extremadura, making it necessary to squint in order to focus.

The animals are frightened at the presence of a human, and scurry away to a corner of their pen. A small goat the color of a coffee bean dances between the legs of its mother. "It was born yesterday," says the goatherd, pointing to it.

His straw hat casts a deep shadow across his face. Small blue eyes, a round face burnt by the sun and wind; a generous midriff that suggests a generous diet. Scraps of alfalfa stick to his shirt, and a rip in his trousers reveals a muscular thigh. Until a week ago, Adrián González, aged 47, married with three children, was the mayor of the tiny community of Plasenzuela, in Cáceres province in the western region of Extremadura, close to the Portuguese border. The village, with its whitewashed walls and tiled rooves, population around 500, can be seen below, boxed in by wheat fields. Plasenzuela owes money, more than four million euros, according to the town hall; around 8,000 euros per inhabitant.

"The village is bankrupt," says González, who resigned as mayor arguing that he couldn't keep it up any longer. "I couldn't sleep at night, I couldn't stand the pressure, I was even taking pills." The local media say that he is the first mayor in Spain to step down as a result of the crisis. Perhaps. The Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces refuses to comment. In any event, as González says: "That's not the issue here."

Plasenzuela is bankrupt. Each inhabitant owes about 8,000 euros

"The issue" came to light in 2008, when he was elected mayor and discovered that there was no money in the village's coffers. A black hole. During his first week in office he reported the previous administration for mismanagement, blowing the whistle on a decade-long scam. Since then the authorities have begun digging into Plasenzuela's accounts, uncovering layer after layer of wrongdoing. This looks set to be the worst case of corruption in the region, with six million euros unaccounted for, and four people charged with defrauding the Social Security, as well as appropriating subsidies, misusing public money, and a host of other financial crimes. European, state, and regional funding has all disappeared without trace. Projects that never existed; workers that never worked; taxes imposed on salaries that were never passed on to the state. A library that has been closed for failing to pay the electricity bill; a swimming pool that can no longer be maintained; empty warehouses that were supposed to provide the jobs to stop the long-standing migration to the city. Plasenzuela was a village that liked to describe itself as having zero unemployment; one of the few in the region whose population increased during the 1980s and 1990s. But now, all that is left are piles of hay bales and stacks of fertilizer, along with the skeletons of half-started building in the outlying areas. The dream of rural development in ruins.

Adrián González says the best way to grasp the full scale of what went on in Plasenzuela is to take a tour round the area by car. He first pulls up at the municipal weighbridge, which is no longer working. He then makes a stop at the textile cooperative that provided work to the community's women, selling its output at one point to the Corte Inglés department store. He brakes sharply at the chicken farms, and then moves on to an empty building once used to train telephone engineers for Telefónica, among them José Villegas, the former Socialist Party mayor, and the main suspect in the investigation into Plasenzuela's finances.

At first nobody in the village seems to know where he is, but a few say they have an idea: he could be in the neighboring community of Torrecilla de la Tiesa, where he runs a retirement home. When we arrive in Torrecilla, we call somebody in Plasenzuela to check the address. When we arrive at the retirement home, we are told: "He's just left. Ten minutes ago. He's got a meeting."

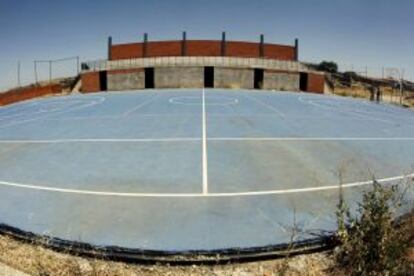

González continues our tour. He parks next to a running track, which he says was part of a projected sports center: a few brick huts, the changing rooms, are still unfinished. The idea was for it to host basketball, indoor soccer and handball. The previous mayor had been given subsidies by the regional government to build it. But the money was never passed on to the building company that was supposed to construct the sports center. The project was abandoned. The central government eventually forced the local council to pay the construction company, despite the fact that the job has not been finished.

By now it is midday, and the temperature hovers around 40 degrees centigrade. Not a soul is to be seen. No cars on the road, and every door closed and window shuttered. The whitewashed walls are blinding. Nobody will be coming out until much later in the afternoon, when they sit outside their houses on wooden chairs, and chat while sipping cold beer. Just about everybody in the village knows what happened, but few are prepared to discuss it. One man attempts to explain what happened. He draws a rough map of the village, with its two roads: one headed to Trujillo; the other to Cáceres. "People here thought that this village was an island, and that nobody would ever find out what was going on," he says. He then draws a series of arrows pushing into the village, explaining that when Adrián González took over, he began to tell the world about what was going on in Plasenzuela: now a judge in Trujillo is heading the investigation while the Specialized Crime Unit, based in Cáceres, keeps digging.

Some 80 percent of the village benefitted from what went on"

Meanwhile, life goes on in Plasenzuela. Around nine in the evening, as the shadows stretch across the village square, the new mayor, Paqui Iglesias of the Popular Party, holds her first council session. She's the third mayor in four years. Iglesias works in the retirement home, the only project dating back to the boom years that has been a success. It is also the village's only source of revenue, other than property tax. Its 32 employees, including the mayor, haven't been paid for three months, and have been considering taking industrial action. Iglesias is reluctant to talk to the media, saying only that her party has promised its support. There is only one person at the council session, which takes place in an ugly, cramped room. The heat is overwhelming, and the councilors are sweating profusely. One wipes his forehead with the collar of his shirt. The new deputy mayor is voted in, work needs carrying out on the retirement home. The municipal secretary, Leopoldo Barrantes, who has also been charged over his involvement in the scams dating back more than two decades, and who is the son of the man of the same name who was involved in corruption in Marbella, reads out the last item on the agenda: funding is available via a rural employment program. "But we can't apply: you all know the reason." The session comes to an end after 18 minutes.

It is only possible to discuss the matter that everybody supposedly knows about, but that few will talk about, in El Labriego, the village's small hotel, aimed at bringing some tourism revenue into the community. It's been faced with stone, and has a pleasant terrace. "A touch of class," says one customer. It was built by the same construction company that carried out most of the work during the years José Villegas was mayor. El Labriego's main claim to fame is that it is where members of the royal family of Monaco would stay when they came to the area to hunt. After their exertions the guests would head over to the village disco. "They weren't really interested in hunting, they were more interested in drinking and dancing," says another customer. "They were very well behaved, they never so much as threw a cigarette butt on the ground," adds another. But Princess Caroline and her friends haven't been back since 2006.

Former mayor who blew the whistle resigned because of the pressure he felt

As the evening wears on, people begin to relax, and the beer and the conversation begin to flow. A Socialist Party councilor remembers how, when Labor Ministry officials would carry out inspections, everybody who had been signed up as employed in any of the bogus companies created by the town hall would have to turn out and pretend that they were gainfully engaged in their respective activity. "We're all to blame, around 80 percent of the village has benefitted in some way," says another Socialist Party councilor, the brother-in-law of José Villegas. A businessman clearly down on his luck sighs and admits that things got out of hand: the mayor's bright red Audi, his three houses, the calls to his girlfriend in Brazil from the town hall and the fact that the judge who married them in Trujillo is now investigating the corruption network. "Basically, the former mayor hasn't a clue, he never really understood what he was doing," says the businessman pulling on his beer.

The town hall's phone bill for May 2007 included 1,157 euros for international calls, and was what first aroused Adrián González's suspicions. The goatherd had just taken up his post as a councilor on behalf of the Socialist Party, alongside Villegas. He was then named deputy mayor and treasurer. He says he began to notice other irregularities, and the following February says he asked the mayor how he was managing to keep the opposition Popular Party at bay. "Simple. I gave a job to the husband of the PP's spokeswoman." González says he then took his suspicions, documented, to the regional Socialist Party bosses. They tried to sideline him. But by July 2008, he had taken over as mayor. The following month, he says that he received a knock at his door. One of the villagers wanted to know about his Social Security payments: "It's your responsibility now that you are mayor," he was told. At this point, González says that he contacted the tax authorities, although he had no idea of the full extent of the village's problems. A few days later he woke up to discover that the hillside where he grazes his goats had been set alight. He was able to put the flames out in time.

Town hall made no Social Security payments between 1997 and 2007

"That's pretty heavy isn't it?" he asks, sitting in his living room. He says that the village is split over his decision to uncover the corruption. He doesn't go out much. He says that his children are asking awkward questions. He no longer sees his general practitioner, preferring to use a medical center in a neighboring village. Piles of press cuttings and other documents lie on the table, figures and calculations. In January 2010, the village owed the Social Security 2.9 million. "From 1997 to 2007, the period when Villegas was mayor, not a cent was paid in Social Security," he says. González claims that around 70 or so people each month were given bogus contracts and signed up to the Social Security. The mayor even signed up some 50 Moroccan laborers that never set foot in Plasenzuela. The aim was to have enough employees to be able to apply for subsidies. But the town hall kept the Social Security contributions. There is no record of the money to be found, and neither is there any record of what happened to the subsidies and funding for dozens of projects that never existed. The important thing during Villegas' decade-long boom is that the village had zero unemployment, even if there were no jobs.

"This is what happens when money is available without having to work," says Damián Ceballos, the owner of the disco where the Monégasque royal family relaxed. His father was the first mayor after the death of General Franco in 1975. Juan Ceballos did a lot for Plasenzuela, and is still remembered and respected. He fought hard to get regional funding to improve the village's water supply: until then the villagers drew their water from a communal well and had no flushing lavatories. He travelled to Madrid and to Brussels, claiming any subsidies that were available to help regenerate rural areas. It was his idea to set up a textile cooperative, as well as the chicken farm, the retirement home, and the library in a converted former police barracks. He saw the future in terms of development, but died of leukemia in 1996, still in his forties. He never claimed a salary.

He was succeeded by Villegas, whom he had groomed for the job. "From being an example of how to get things done, the village became a disaster area. Things are so bad that we are using the blank side of the phone bills to Brazil for photocopying," Ceballos says.

He has a press cutting; it's a story from a local newspaper about his father. "He has virtually eradicated unemployment in the village," says one standout quote. But shortly before he died, Damián says he would constantly ask: "How long can the EU anesthetic last?"

Anesthesia. Plasenzuela is a microcosm of the problems afflicting Spain on a larger scale, a symbol of something that might have been, but that ran out of gas halfway along the way: the chance of money for nothing, of development subsidies with no questions asked. An inability, or refusal, to distinguish between the private and the public: telephone calls to Brazil from the town hall, weekends in Puerto Banus.

The debt is currently being negotiated with Madrid, not Brussels. And now the new mayor travels to the capital by bus to meet with "some gentlemen in suits who calculate things on their computers."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.