Where is Kelly Agbon's son?

Nigerian immigrant has spent 11 years fighting to get back his child The family was separated by an apparent administrative error

She was a 21-year-old illegal Nigerian immigrant who worked as a prostitute on the streets of Murcia - according to the version later given by authorities. Her name was Omosefe Ijesurobo. On October 13, 2001, the police arrested her and took her to a detention center to await deportation. Nine days later, her lawyer filed a request for her release: "She has a one-year-old child to support," he warned the judge.

But on October 24, Omosefe was deported. Inexplicably, the authorities separated her from her child. The little boy remained in Spain. And the little boy had a father, also Nigerian, who also remained in Spain, but not with his son. His name was Kelly Agbons Bejet.

Nearly 11 years later, that baby - whose name is Osagi, if it hasn't been changed - lives with a different family, the family that adopted him. He was given up for adoption because the Spanish administration deported his biological mother by mistake, and because it did not believe his biological father, who immediately demanded to get him back.

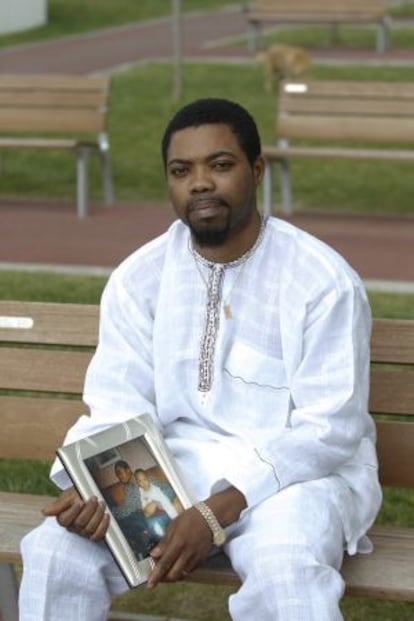

After a decade of appeals in various Spanish courts, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg has just ruled in favor of Kelly Agbons, who was 25 the last time he saw Osagi. Now 36, he has two other children with another woman but he is still demanding to get his first-born back.

This is a case of theft. Spain has stolen my child," Agbons insists

"This is a case of theft. Spain has stolen my child," he tells anyone who will listen.

Strasbourg has established that the Spanish state is guilty, but it cannot return Osagi to his biological father, so it is forcing the government to pay him 8,000 euros in damages.

"Eight thousand euros? Not 8,000 and not 100 billion. I don't want that money. I want my son," he says.

This is the story of a family separated by an apparent administrative error that the authorities have at no moment tried to rectify. Kelly says that to get Osagi back he will go "to the end with this, with God's help," even though that would mean separating the boy from the people he now considers his family. Kelly tells his story inside his home in Santa Coloma de Gramenet in Barcelona province, where he lives with his current partner and their two children, Emmanuel, age two, and Elisabeth, who is one. "I tell them they have a brother," he says.

8,000 euros? Not 100 billion. I don't want that money, I want my son"

Kelly, Omosefe and Osagi arrived in Spain in two boats in late 2000; first the father, and then the mother and the baby, who was born in Morocco. They settled down in Murcia, where they moved in with a relative of hers. But they could not find a job, and they had no legal residency papers. So in May 2001, Kelly decided to try his luck in Barcelona. "I looked for work as a field hand, and I slept in Plaza de Cataluña."

He says he used to go down to Murcia every so often, on weekends, to see Omosefe and the baby. He claims Osagi was never left unattended. Regarding the fact that Omosefe ended up working as a prostitute and that the baby was being cared for by a couple who were friends with her, Kelly gets passionate: "There are prostitutes all over the world, but they don't take away their children."

Two days before her deportation, Omosefe's file shows that her lawyer warned the court about the child. Omosefe and Osagi were nevertheless separated, in breach of the European Convention on the Rights of the Child. Either the court did not record the petition, or it ignored it, or it failed to coordinate with police in time to stop the deportation. None of the rulings derived from this case explains exactly what happened - because the case was not about that, but rather about whether Osagi could be given up for adoption or not.

Murcia authorities immediately realized a mistake had occurred, among other reasons because the media denounced this and an identical case involving another Nigerian child separated from his deported mother. The administration immediately tried to get mother and child back together again by asking the Nigerian Embassy to locate Omosefe. But she never turned up. Years later, in court, the government alleged that once deported, it was impossible to bring the mother back, and that the little boy had not been signed up in the Civil Registry, which left him in a legal limbo and made him a ward of the state.

Kelly Agbons does not believe this story. He says he has been in touch with Omosefe all these years over the phone - he claims she has put him in charge of finding the child - and that the Murcian government could have done the same. He is convinced that what happened to Omosefe "would not have happened to a Spanish woman" and that "they treated us this way because we are Nigerian."

Kelly went to a clinic to take a paternity test and obtained authorization from authorities to get a blood sample from Osagi to compare their DNA. But before performing the test, the clinic showed him the bill: 200,000 pesetas (1,200 euros). He did not have that kind of money, so the test was not performed. Nobody told Kelly he could request free legal service and have the state pay for the test.

That was in January 2002, when Osagi was just a year-and-a-half. Months later he was adopted by a Spanish couple, with whom he has been living ever since. Kelly's lawyer says they will take their case to the United Nations Human Rights Committee.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.