When brotherly love is a crime

Incest is viewed very differently depending on the country in which it occurs A German couple has fallen foul of the law, while in Spain it is tolerated

Incest is the last barrier. Today's society accepts - legally, at least - almost any type of relationship between adults, yet alarm bells ring where siblings are concerned. The cases of Patrick Stuebing and Susan Karolewski in Germany, and of Daniel and Rosa Moya in A Coruña, show that it is possible for two close relatives to fall in love and form a family just like anyone else. But the different way both couples were treated - obtaining legal papers in Spain, facing a criminal conviction in Germany - underscores the fact that criteria differ even within European Union countries. In any case, there is no denying that siblings who love each other, have sex and produce children, prove problematic both from social and legal standpoints.

The European justice system has decided that Germany may legally persecute incest by ruling against the siblings Stuebing and Karolewski, who had four children together (two of them with mental disabilities). The couple had argued that Germany's ban on incest violated their fundamental right to family life. The punishment for incestuous relationships is two to three years in jail.

But in Spain, incest ceased being a crime in 1978, even though marriage continues to be off limits for siblings. Thus, the courts ruled in favor of Daniel and Rosa Moya, who demanded the right to officially register their children.

In both cases, the siblings had been raised in different families before eventually deciding to share their lives and face the social stigma of a taboo that is branded into our collective conscience. But the question remains: is it necessary to legally persecute couples made up of consenting adults, regardless of how much social rejection they may attract?

The European justice system has decided that Germany may persecute incest

Manuel Pérez-Alonso, a professor of genetics at Valencia University, says that every ban has a "real and biological basis." In this case, it is the risk of consanguinity. "The problem lies in the recessive genes," he explains. This means that a person may carry a mutation for a disease - cystic fibrosis, for example - but that disease does not manifest itself. If that person's partner carries the same mutation, and both pass it on to their descendants, that factor will show up. "And none of us know what mutations we carry. We all have dozens of them."

If the parents are siblings, then the probability of both mutations coinciding in the baby is 25 percent, much higher than for the general population, this expert says, calling it "a macabre lottery."

"This is what traditionally happened in royal families, where there were a lot of blood relationships," he adds. It is also what happens to purebred animals and selected plants. In these cases, consanguinity is actively sought in order to encourage certain genetic traits, but that comes with the risk of unwanted adverse effects. "That is why they say, and it's true, that purebred dogs are more delicate," says Pérez-Alonso.

Although people do not make decisions based on probabilities, it does seem obvious that ancient societies noticed the process at work, and even though they knew nothing about genetics, they established barriers to prevent it from occurring.

Incest ceased being a crime in Spain in 1978, although marriage is off limits

There are other motives for the social rejection of relationships between close relatives besides the biological ones, and economics is chief among these. The sociologist Enrique Gil Calvo says that "the taboo of incest made sense in earlier family-based societies, whose economic structure depended on the marriage contract, which passed on the family assets through inheritance."

Those negotiated marriages "were based on the rule of outbreeding - that is to say, the exchange of sons-in-law and daughters-in-law, which was the fabric of the social capital. Thus the prohibition of incest, to reinforce the social capital networks."

Naturally, the situation has since changed. "We no longer live in a society of families but in a society of individuals," says Gil Calvo. "And in these new relationships of interpersonal couples, the rule of outbreeding and the ban on incest no longer make any sense. People today are free to pair up with whoever they want, as long as their partners are also freely consenting adults. Incest no longer makes any sense as a crime or an offense - not so sexual intercourse with a minor, which is still defined as a crime as it is based on coercion. If German legislation retains incest as a crime, it is because of the inertia of atavism, since the Lutheran religion - unlike Catholicism, much more open and tolerant - is based on a core family model that is rigid, closed and archaic."

Juan Aranzadi, an anthropologist and professor at the distance university UNED, believes that the recent ruling by the European Court of Human Rights supporting Germany's decision to jail Patrick Stuebing for 14 months for "the crime of incest" is the result of "confusion between blood relationships, sexual relationships, procreation relationships and genetic relationships." But beyond that, "the main human problem triggered by the Strasbourg court's judicial decision and German legislation on incest is the role, the function and the limit of state intervention, as well as the state's regulation of blood relationships, sexual relationships and the reproduction of its subjects or citizens."

The taboo of incest made sense in earlier family-based societies"

"And if the court had concluded that the German state does not have the right to ban incest, what power does it have to force the German state to change its legislation and respect human rights?" Aranzadi wonders.

Regarding Patrick Stuebing's conviction, Aranzadi says he is not familiar with the exact way that German legislation defines the crime of incest, but that "in European legal culture, derived from Roman Law and the Church's Canonic Law, incest is defined as sexual intercourse between relatives of different types and degrees." Yet, from a strictly legal viewpoint, "Patrick Stuebing and Susan Karolewski, like their different surnames clearly indicate, are not legally related and cannot thus commit incest." As a matter of fact, he continues, "long before anthropologists insisted that blood relationships are a cultural reality whose connection with sexuality and procreation is neither clear nor transparent, Roman Law had already introduced the distinction between pater (father) and genitor (begetter)," he notes. And the new models of family, together with medical advances, have turned these concepts on their head. Yet "Strasbourg appears to favor the opposite direction, offering a legal justification for the biology-based interpretation of the cultural category of incest, a justification that is logically and epistemologically inconsistent."

This sociologist goes even further. "It is interesting to note that the frequency of incest in our society is very different in all three penalized or banned types: the most frequent kind of incest is between father and daughter, which is usually 'forced,' while the least frequent one is between mother and son. Somewhere in between there is incest between brother and sister, which is usually sought by both and tends to happen between siblings who were not raised together but separated in early childhood, and who are reunited as adults."

And while incest between the father (or stepfather, or mother's partner) and daughter usually has "devastating consequences for the physical and mental health of the daughter," adds Aranzadi, "there are no known negative personal consequences derived from a mutually desired incestuous relationship between siblings." Besides, "the practice of incest lacks any noticeable effect on the institutions of marriage and family, and it has been their constant shadow throughout history much more frequently than is believed."

We no longer live in a society of families but in a society of individuals"

Back to the Strasbourg ruling, Aranzadi says that "if Patrick Stuebing and Susan Karolewski are not legally related, they are not (legally) siblings, and what the German legislation prohibits is incest defined as a sexual relationship between relatives, meaning that this legislation does not apply. In order for it to be applicable, German legislation should ban biological incest, not cultural incest - that is to say, sexual intercourse between people who share a certain percentage of genes, regardless of their cultural or legal relationship. And that prohibition should be expressed in biological terms."

This opens up other questions. "Does the Strasbourg tribunal believe that the German state has the right to legislate on the sexual conduct that is most favorable to the genetic health of its population? Does the Strasbourg court feel that the German state has the right to prohibit sexual relationships and the reproduction of people whose genome represents a risk to their descendants? Strasbourg continues to equate sexual relationships and reproduction, and it can think of no other way of stopping a couple from reproducing than to prohibit them from having sexual relationships," says Aranzadi.

The most frequent kind of incest is between father and daughter"

And there is another issue at play, adds Nùria Terribas, of the Borja Institute for Bioethics. These siblings "are not to blame for the fact that chance made them come together as a couple when they were siblings, although they did not know it at the time." Once they found out, were they supposed to break up the relationship? Terribas thinks that this is "an extreme interpretation of the law, which would force the undoing of a family. From the viewpoint of consequentialist ethics, you cannot obviate that they have children, and apparently with no more problems than other families."

The different solutions found in both cases prove that dealing with incest is far from an open-and-shut case. But in increasingly pluralistic societies, there is one thing that should not be forgotten: "This is something that is decided by two consenting adults," says Terribas, even though "classic morality places it on the same level as abuse."

The question is whether this is enough of a reason to force these couples to do something very irrational: to love each other only like a brother or sister.

"If I die, my kids can inherit from me"

Daniel and Rosa Moya Peña, a brother and sister who have had "a conjugal relationship" for the last 35 years, are not worried about the fact that Spanish law does not allow them to marry. And they did not take it personally when they heard about the recent ruling by the European Court of Human Rights supporting the criminalization of incest in Germany. Incest ceased being a crime in Spain in 1978, and in their long battle to obtain legal recognition "with full rights" for their unusual situation, the couple from Cambre (A Coruña) have managed to be recognized as the parents of their children Cristina, 26, and Iván, 19. Legally they are now a family.

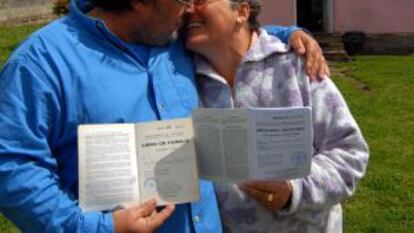

A legal ruling says that Daniel is no longer officially his children's uncle, and Rosa no longer a single mother. They are now in possession of a document known as the libro de familia, or family book, where officials note marriage dates and children born from the relationship. Both kids have changed their ID cards to reflect their real surnames: Moya Moya.

"Now, if I die, my children can inherit from me, because they are legally my children, not my nephew and niece. I would have liked for this to happen earlier, because they had a hard time as kids due to people's morbid curiosity," says Daniel, 57. "Now I will keep fighting to try to get Social Security to recognize the woman whom I consider my wife and the love of my life. Many unmarried couples are given the right to a pension when one of the partners dies, on the basis of years spent living together."

It was a celebrity's lawyer who told them about the possibility of legally becoming a family. Back then Daniel, Rosa and their children were making the rounds of the television gossip shows, "showing our faces," as Daniel puts it, and letting the world know about their unusual love story, which began when they still did not know that they were closely related.

The same Civil Code whose article 47 prohibits direct relatives from marrying (although cousins may), also establishes that progenitors who happen to be siblings may be legally recognized as the parents of their children. But this requires court authorization. The Moya family spent over two years battling for this right, and all four family members had to testify in court. Even so, the attorney's office opposed the final ruling of November 2010, which was as concise as can be: "I must declare that Daniel Moya Peña is the father of Cristina and of the minor Iván for all legal purposes."

"We had to pay a lawyer and a court representative to get the damned libro de familia," complains Rosa, 52. But with that court decision, over at the civil records office it took "under five minutes" to change their children's birth certificates to reflect the fact that Daniel is their legal father.

Until then, only Rosa's full name appeared on the libro de familia; the space for the father's name read simply "Daniel." That was the most that the civil servant would do for them when Cristina was born in 1985. "He kept insisting on writing down 'unknown father,' but how could he do that since I was standing there in front of him?" says Daniel. Rosa recalls bitterly that when Iván was born in 1993, they tried to convince them to give him up for adoption.

The Moya family is used to "fighting and facing the music" over a relationship that was taken to the silver screen in 2005 in a movie called Más que hermanos (or, More than siblings). "We fight for our rights, and if we have them, we want to exercise them. The [fuss over] incest is puritanism. Who gets hurt by my relationship with Rosa?" asks Daniel. They met in Madrid in 1977, without knowing that they were born to the same mother and father. The latter had separated two decades earlier, breaking up a family with seven young children.

The mother raised Daniel and one daughter, never telling them that they had other siblings. Rosa grew up in an orphanage with a twin brother, who is deceased. They were already a couple when they found out about their direct relationship, and they broke up. But five months later they got back together. Still, at first they kept the true nature of their relationship secret.

"We had two relationships: inside our home we were just like a married couple, and outside we pretended to be siblings who were just roommates. Until one day we got sick of it. If people are able to deal with it, fine, and if not, that's fine too," says Daniel, who insists that their case is different from that of the German couple who knew they were siblings when they met, besides the fact that she was underage. "Besides, their children did not come out right."

"'So you're retarded? That's gross.' I used to hear that all the time, at school and on TV," adds Iván. But he and his sister "don't care" about the curiosity their parents' relationship creates. They had a rough time as kids, but "the only thing we lost were days of school because of all the trips we made," in reference to the numerous television programs they appeared on.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.