A new Titian is born at the Prado

The restoration team at the museum is working on a version of Saint John the Baptist The painting ended up inside a church, where it survived the trials of the 20th century

Competition is tough these days at the Prado Museum’s restoration workshop, which could be described as a kind of emergency room for old works of art — a place where pieces by Raphael, Goya and Van der Weyden all vie for attention. But amid these dazzling masterpieces, there is one painting that shines discreetly in a corner, its colors dampened by centuries of oblivion, war and devastatingly bad restoration jobs. It is a religious scene by Titian, and it represents the latest significant find — that has been made public — by the museum’s scientific team. This select and highly trained group of around 15 curators and 20 restorers has been making the news in recent times with a steady stream of findings that they have plucked out from the museum’s extensive holdings: a previously unknown Brueghel here, a copy of the Mona Lisa, made simultaneously with the original, there, and now the new Titian.

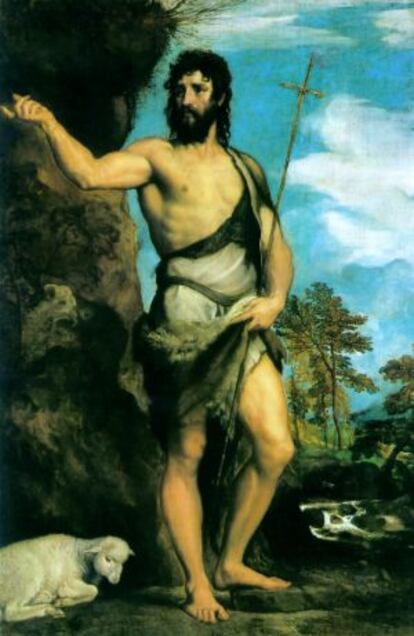

Although the painting is being kept under wraps at the workshop until the restoration work is complete, the image it depicts looks familiar. It is another version of the famous Saint John the Baptist, which the Venetian master made in 1542 and is kept at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. Another version of it exists inside the monastery of El Escorial, where it arrived in 1577 through a donation by King Philip II of Spain, who was an admirer of Titian. This particular painting was restored for the last time in 1999, together with The Last Supper.

The saint who is now the object of attention at the Madrid museum’s workshop is part of what is known as “The Scattered Prado,” a collection of 3,100 works that were sent out to various parts of Spain when the headquarters’ collection grew disproportionately large following the annexation in 1872 of the holdings of the Museo de la Trinidad. The painting ended up inside a church in Almería, where it survived the calamities that the 20th century had in store for it, including changing tastes and the Spanish Civil War.

And there it sat until it was noticed by Miguel Falomir, head curator of the Prado’s Department of Italian Renaissance Painting, who is drawing up a detailed catalogue of Titian’s work, which he pledges to have ready by the end of the year. A renowned Titian scholar, Falomir put together an exhibition at the Prado in 2003 that everyone at the museum agrees was a turning point in the gallery’s academic ambitions. Falomir figured that a more detailed study of the master might yield interesting results. He was right.

The curator hinted at this latest discovery of a Titian painting in a text he wrote for the Center for Advanced Studies in Visual Arts at the National Gallery in Washington, back in 2010: “The restoration and the technical analysis of nearly the entire collection of the Prado has coincided with the creation of a detailed catalogue and significantly contributed to, for instance, changing a few attributions and dates. Besides that, the X-rays and the infrared reflectography, together with pigment analysis, yielded new information that sheds light on Titian’s working method and the varying periods of his creative work; the presence of sketches under the paintings, more abundant than previously believed; the constant changes he introduced while he made his compositions evolve; and the habit of reusing canvases in his latter decades. This technical material is particularly useful to understand how Titian’s workshop worked, especially in the production of replicas, an issue on which the Prado is well endowed with examples.”

“Nobody knew of its existence,” admits Matteo Ceriana, director of the Gallerie dell’Accademia, speaking from Venice. Ceriana has seen the painting, and has no doubt that it was made by the Venetian master himself, Tommaso Koch reports. “It ended up inside a church. \[...\] It is not exactly like ours, nor like the one at El Escorial, and even then all three versions are interconnected. Saint John the Baptist is not a very complex topic. And an artist like Titian, who was so great and who lived for so many years, was forced to face the same subject matter on several occasions. He tried not to repeat himself; at least he tried to reinvent himself.”

Titian tried not to repeat himself; at least he tried to reinvent himself”

Experts confirm that it was a common practice among great artists of that period (and also of this one, if one thinks of Damien Hirst for example) to revisit certain subject matter. Often this was done at the request of the buyers themselves, who wished to have the same experience as others had before them.

But a creator of Titian’s standing could not allow himself to fall into a crass repetition of past glories. That is why this third Saint John the Baptist — which, as the other two, depicts a lamb and a landscape — is much more than a mere copy made by a workshop, as the studies attest.

The details of the restoration process will not be revealed before the fall, when the entire process is presented at an exhibition. The publication of the detailed Titian catalogue will come later, containing the itemized listing of his entire production and that of his workshop. This will clear up existing confusion over authorship issues.

Last February, curators at the Madrid museum revealed that they had found a replica of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa that was painted simultaneously with the original by one of the master’s favorite pupils, probably Andrea Salai or Francesco Melzi.

Although many copies of La Gioconda exist, this is the earliest, in that it was painted virtually at the same time, inside Leonardo’s studio, and not after his death as previously believed.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.