R is for refusal, not rectification

Royal History Academy rules out amending a hagiography of General Franco

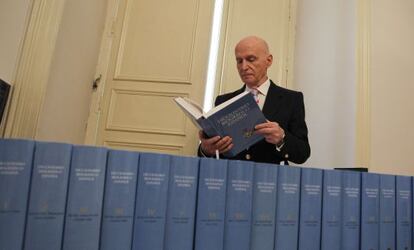

Seven months after the Royal History Academy (RAH) said it would rectify a number of entries in its Spanish Biographical Dictionary after a favorable biography of General Francisco Franco prompted outrage at home and abroad, the 50-volume collection remains unchanged.

After more than a decade of writing and at a cost of 6.5 million euros of taxpayers’ money, the first 25 volumes of the dictionary were published last June to a storm of criticism over several entries, particularly one seen as sympathetic to Franco.

“In recent days, legitimate criticisms have emerged of aspects of some specific entries on figures who, because of their historical proximity and role, inevitably generate debate among experts and broader society,” the academy said in a statement last June, adding: “There may doubtlessly be a subset of entries that require, in view of the debate, a historical and editorial revision that may need to be incorporated quickly into the digital edition and later paper editions.”

Following the uproar, which produced calls in the Senate and Congress to stop public funding of the RAH, the academy said all dictionary entries were signed and that there was a disclaimer in each volume explaining that the authors themselves were responsible for their own contributions.

When deciding how to complete it in a reasonable but rapid timeframe, the academy opted for “the principles of intellectual freedom and of responsibility of the authors,” it said.

However, in response to the public outcry it agreed to task a commission with revising around 3,000 of the work’s more than 40,000 entries, covering figures dating back to the sixth century of the modern era.

But within months, three members of the commission threw in the towel and resigned. They were replaced by a number of leading academics and historians. One of them, Faustino Menéndez Pidal, a specialist in heraldry, told provincial newspaper El Heraldo de Aragón that “not much will be changed in the revision.”

In an interview with EL PAÍS, Menéndez Pidal said that “not much” was a “relative term,” adding that he was more interested in dates and places. “These aspects to do with qualifying people, whether somebody was taller or shorter, are about objective criteria,” he said, avoiding discussion of the Franco biography.

Other sources at the RAH agreed that there would not be “substantial changes.” In fact, all entries will be left as they are.

The head of the RAH, Gonzalo Anes, says the organization “will not censor authors involved in the national biography project,” adding: “It is very difficult to achieve absolute objectivity.”

At the center of the row is the entry covering the life of Franco, written by Luis Suárez, an 86-year-old Franco apologist who says Franco “became famous for the cold courage which he showed in the field” while a young officer in Africa, adding that his brutal years in power saw him “set up a regime that was authoritarian, but not totalitarian.”

The historian failed to mention the tens of thousands of people killed during the Franco era and at no point did he describe him as a dictator.

Suárez is a friend of the Franco family and a senior figure in the Brotherhood of the Valley of the Fallen, a group that takes its name from the basilica where the generalísimo, as Suárez prefers to describe him, was buried in 1975. The group is actively opposed to attempts over the last decade to identify the mass graves of the victims of Franco’s death squads. Historians have estimated that half a million people were killed during the Civil War sparked by Franco’s insurgency against the democratically elected leftwing Republican government.

For many years, Suárez was one of the few historians allowed by Franco’s family to study the personal papers of the man most Spaniards recognize as having been the country’s dictator for 36 years from 1939. In 2005, Suárez published a biography of the dictator.

The biography of Second Republic President Manuel Azaña was written by academy member Carlos Seco Serrano, to the detriment of Santos Juliá, the Republican leader’s best-known biographer, whom the academy ruled out.

In other entries consulted in the 20 volumes so far available (up to the letter F), the atrocities committed in the Civil War by Franco’s forces are systematically omitted, while those committed in the Republican zone are given minute attention.

The dictionary also includes admiring profiles of former Popular Party Prime Minister José María Aznar and his then culture minister, Esperanza Aguirre, who provided the initial funds for the project.

The Education Ministry refused to allow the collection to be distributed in state libraries until a thorough revision was carried out. The ministry has refused to comment on whether it will maintain the veto.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.