Medical group accused of "privatizing transplants"

Spanish medical chief points finger at German organization charging recipients to cover costs

The head of Spain's National Transplant Organization (ONT) is denouncing a German group that, he argues, "wants to privatize bone marrow transplants."

"What DKMS is doing is hitting the Spanish system below the belt," says Rafael Matesanz, the ONT chief, about an organization that has been active in Spain since October. After several meetings with DKMS executives and letters asking it to cease its activity, Matesanz has reported the case to the state attorney, claiming that the company may be in violation of the law.

DKMS, founded in Germany in 1991, branched out into the United States in 2004 and showed an interest in Spain following the case of Hugo Pérez Santos, a 35-year-old from Avilés (Asturias) who was waiting for a bone marrow transplant at a German hospital. The company launched a campaign to find potential donors, and obtained data from 1,204 Spanish volunteers, who are now listed on the world donor registry as "belonging" to DKMS.

This means that if the ONT needed to use the bone marrow of any of these individuals, it would have to pay DKMS 14,500 euros for it. The company gets the biological material for free, taking advantage of "a very emotional moment" such as a sick person's plea for help to expand its donor portfolio. After the donors are called up to donate their marrow for free, DKMS charges recipients 14,500 euros to cover costs.

According to Fundación Josep Carreras, whose registry is the only one in Spain that is officially approved to coordinate bone marrow transplants, DKMS' prices are 6,000 euros above the usual fees. The foundation offers prices of around 8,500 euros.

DKMS wrote to EL PAÍS to say that it is a health foundation and that its actions are legal.

"Due to the great number of requests that DKMS receives from Spanish patients, we consider it our obligation to continue to support them, especially since the law allows it," reads the message. "According to the pertinent legal analysis conducted by DKMS, all activities carried out in Spain respect Spanish legislation and rules."

Matesanz grants as much, but indicates that behind DKMS is a beauty industry multinational called Coty. The ONT director got moving when he learned that DKMS had sent letters to Spanish doctors claiming that they had permission from ONT to operate in Spain, which was false. Also, it turns out that the legal battle was started by the German company, which brought a suit against the ONT on charges of damaging its reputation.

The ONT believes that DKMS is in breach of the law for a number of reasons, including: its attempts to obtain donors in Spain without previously alerting regional governments; having sent samples to Germany, which could constitute tissue traffic; collecting personal information from Spaniards without authorization from the Spanish Data Protection Agency; and taking advantage of high-profile cases to find new donors, when Spanish legislation says that donations must benefit specific individuals.

This last point is very important, says Matesanz, because it could endanger the Spanish transplant system, in which donors do not charge and recipients do not pay, and where donors do not get the opportunity to choose who it is they are donating to, unless it is a relative. Things are different in other countries, such as Germany, where, the ONT chief admits, DKMS' actions are "completely legal."

This distinction between systems that are free and systems that involve payment means that France and Brazil do not let DKMS operate on their territory, while Poland and the US do.

"This DKMS campaign is unfair - they solve problems"

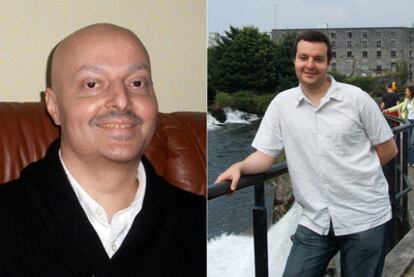

Hugo Pérez Santos, a 35-year-old from Avilés (Asturias), has been battling leukemia for the last three years. After failing to find the right treatment in Spain, he says, he tried his luck in the German city of Dresden, where a hospital agreed to attempt what no Spanish specialist had wanted to do: a bone marrow transplant in which the donor was his brother, who was only 50-percent compatible with Hugo's own marrow.

He was in Dresden when he was contacted by DKMS, a private organization specializing in finding bone marrow donors and putting them on a proprietary registry (the German state registry is ZKRD). DKMS then charges recipients around 14,500 euros.

"One of the founders of DKMS works at the hospital where I got the implant," recalls Hugo. "They offered to try to locate donors who were 100-percent compatible for me. [...] A group of friends worked with DKMS to put on a drive for new donors in Avilés. The city lent us a sports center. On October 16 we attracted 1,231 donors in Avilés. The slogan was 'For Hugo and for Others'."

It was this campaign that tipped Spanish authorities off to DKMS' activities in Spain, which might be illegal here given that the transplant system is based on anonymity and altruism. The law specifically says that donors cannot know who they are donating to, unless it is a relative.

"The main aim is to save lives and increase the number of donors, not to hide behind bureaucracy and the law," states Pérez. "I don't understand this rejection of [DKMS'] actions."

Pérez was working for a global hotel chain in Ireland when he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia in 2008. He went back home and started to see doctors. But nobody could guarantee a solution for him, he said. Then, when an infection forced him to go to a Valencian hospital, a doctor recommended several centers in Rome, London and Dresden.

"I chose to travel to Germany because they were ready to go further than anybody else," says Pérez. "Since no 100-percent-compatible donors were turning up, they agreed to try a transplant with bone marrow donated by my brother. [...] In Spain they refused because they thought it useless and too risky. But I had to take risks; I couldn't just sit around and do nothing."

The transplant took place last October. Now, the healthy cells are battling the malignant cells. "It is too early to know the result. I know I still have 4.5 percent of carcinogenic cells in my marrow, but we don't know whether the disease will make progress or not."

So far, no fully compatible donor has turned up, but he wants to keep trying. "Of course I'm really satisfied with DKMS' support. At least they try and they show concern. They go further than the others. I don't know why they are being rejected. The fact is, there are only 90,000 registered donors in Spain, versus 2.5 million in Germany. And half the bone marrow transplants carried out in Spain are done with German donations."

Hugo believes that Spain's National Transplant Organization makes things too difficult. "The main thing is to save lives, so the more donors, the better. DKMS is solving problems. The campaign against them is unfair."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.