"Sunken, askew and full of scaffolding"

Mistakes are part of the charm of Atocha station, Ricardo Aroca says in his new book

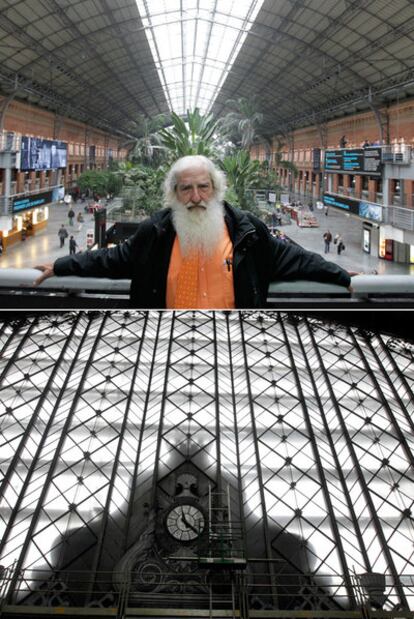

In the 19th century, train stations had high ceilings so that the smoke from the engines would not suffocate the public. "Now trains are electric, but stations are still huge - out of pure grandiloquence." With a venerable professorial air, Ricardo Aroca, ex-dean of Madrid's College of Architects, paces along the towering hall of the old train station. Atocha is one of the places he discusses in his new book, La historia secreta de los edificios (or,The secret history of buildings). "It's a good building to explain, because it contains so many mistakes," laughs Aroca. "Poor thing, it's sunken, askew and now full of scaffolding."

But why? The "underlying error," he says, is its location. Since trains cannot climb steep gradients, the station had to be sunk under the surrounding ground level, complicating access. An approach embankment miles long might have eased the gradient, but would have been very costly. Or the station might have been set further from central Madrid, "which was politically and economically undesirable, as visibility and convenience were important." Another option that was "unlikely in the 19th century, when trains still belched smoke," was to have the tracks below and the station above. This idea, the basis of many modern stations such as Seville's Santa Justa, the professor's favorite, might have been carried out in the renovations of 1985 and 1990, "dismounting the original iron structure and raising it to street level," says Aroca. This is not just a boutade: "Harder things have been done."

Trains cannot handle tight curves either. This is why the station is askew with respect to the square it fronts on, the Plaza de Carlos V, which Aroca calls "a strange non-place," a confused confluence of avenues with an ill-defined shape. The station's orientation meant that you always had to enter by a side door. All that front facade for nothing.

Yet Atocha was a great station. Designed by a disciple of Eiffel, it was one of the greats of its time. "It was Madrid's tardy entry into modernity," says Aroca, whose book explains some features of the iron-and-glass architecture. For example the big structural members are made of multiple sheets of iron, held together by rivets. A rivet is a big iron pin with a round head on one end, heated red-hot in a furnace, inserted through holes drilled in both sheets, then hammered on the other side to create a round head. As it cools and shrinks, it pulls the two sheets tight together. In most uses rivets have now been replaced by bolts, or welding. Another curiosity of the station is the gauge of the tracks, different from the European standard. "The engineers gave a technical excuse, but it was obviously to hinder a possible French invasion, only 50 years after Napoleon's occupation of Spain."

"In the 19th century, the specific needs of trains created an instantly recognizable type of building," says Aroca. "Today, architects can make stations any way they like. They are usually monumental, but might be much smaller and cheaper." At Atocha, the old station now serves as a vast anteroom to the new one, designed in several phases by Rafael Moneo from 1985 onward. "It's a good job, but let's say it doesn't inspire much enthusiasm." Aroca considers that longer-range budgeting and planning might have given greater unity to the whole. "The new parking structure is unfortunate, and the monument to the March 11 bomb victims, which looked good in the competition, is a lump. The total effect is confused," he says. "The result is disoriented travellers, who have to be continually looking at signs to get where they want to go. And when you have to put up lots of "dangerous curve" signs, it's because you've built your road wrong."

Lastly, the scaffolding. It was put up some weeks ago for restoration work on the facade and the corner towers. It will last 12 months, and cost 1.3 million euros. The glass curtain wall will be restored, and, on the gable, the sculptures of mythical winged beasts, half-lion, half-dragon, which presumably, like the trains of yesteryear, belched smoke.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

Últimas noticias

Most viewed

- Pablo Escobar’s hippos: A serious environmental problem, 40 years on

- Reinhard Genzel, Nobel laureate in physics: ‘One-minute videos will never give you the truth’

- Why we lost the habit of sleeping in two segments and how that changed our sense of time

- Charles Dubouloz, mountaineering star, retires at 36 with a farewell tour inspired by Walter Bonatti

- The Florida Keys tourist paradise is besieged by immigration agents: ‘We’ve never seen anything like this’