Berlanga's Blue Division notebooks

EL PAÍS dusts off the diaries written by the late Spanish filmmaker on the Russian front. The pages are bursting with political writings, poems and drawings

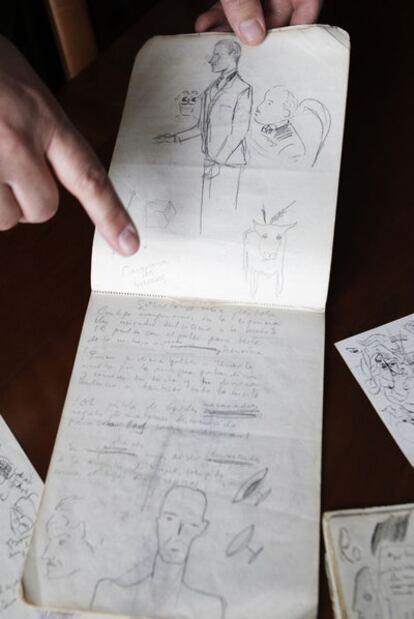

Just taken out of the safe and on top of a table to be photographed, they could just be old bits of paper and nothing more. However, they might also be considered a Rosetta Stone of Spanish cinema. They are the diaries written by the 20-year-old Luis García Berlanga during his time on the Russian front with the Blue Division, the group of Spaniards who volunteered to serve alongside the German army during World War II.

Inside are the filmmaker's first characteristic scribblings, his political writings marked by a romantic vision of the Falange, film criticism, a novel, dozens of drawings... and above all poems, a lot of poems, almost all of them dedicated to the love of his youth, Rosario Mendoza, who was actually one of the reasons he enlisted in the Blue Division.

"Because deep down, Luis wanted to be a poet," says Basilio Rodríguez, owner of the Sial publishing house and responsible for the publication of these notebooks. Last Sunday marked a year since the death of the Spanish filmmaker, and this is the first time that these diaries have been made public.

"In my family we didn't even know they existed," says José Luis García Berlanga, the director's eldest son. "Until one day, when [film expert] Miguel Losada called me and spoke to me about a publisher who had them and wanted to publish them, and I was truly shocked. 'Who has them and why?' I asked."

"I have them because his father gave them to me, but he always made it clear that they weren't a present, rather that he had given them to me for them to be published," says Rodríguez.

It was back in 2006, over one of the lunches they used to have with writers such as José Alcalá-Zamora, Luis Alberto de Cuenca and Andrés Aberasturi, as well as poets such as Beatriz Russo, Sol de Diego and Pura Salceda, that Berlanga confessed to Rodríguez that he had a lot of poetry that he would like to see published. He handed over the manuscripts, but their publication ground to a halt after the filmmaker broke his hip and became housebound. After his death on November 13 last year, Losada, head of film at the Ateneo de Madrid arts and sciences center, and a poet published by Rodríguez, spoke to the director's son about publishing them and he agreed. The book, put together by Losada and due to be launched on November 23 at the Cinema Academy in Madrid, contains almost the complete transcript of the diaries and many of their pages ? bursting with drawings, color and compressed text ? are reproduced in facsimile format.

They show a fascinating vision of Berlanga the poet, the kid who went to Russia on July 14, 1941 for two reasons: to try to get a pardon for the death sentence imposed on his father, a Republican deputy in Alejandro Lerroux's party; and to impress a girl, Rosario Mendoza. They also contain a lot of creative writings: Soneta a una pistola, the only one of Berlanga's poems published in his lifetime; texts about the Marx brothers, director Josef von Sternberg and writer Paul Valéry; an outline for a possible script; several Japanese haiku poems; fragments of a speech; a text that would be the basis of his short film El circo; drawings upon drawings with self-portraits and even a profile of Rosario Mendoza... And not to mention a laudatory article about José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Spanish Falange. "It's logical," explains Losada. "He was 20 years old and his best friend was José Luis Colina, an anti-Francoist Falangist, who put Primo de Rivera's romantic vision in his veins."

Although Berlanga didn't fire a shot in Russia, his service entailed a certain degree of danger. Every other day he had to climb up a giant water tower near Stalingrad to observe the Russians 500 meters away on the other side of the Volkhov River. For a whole year, nothing significant happened. But on his day off, Soviet cannons knocked down the tower, killing another watchman.

The notebooks confirm Berlanga as a great writer; the cinema gained a genius, but poetry lost an artist. But as both Losada and Rodríguez say: "He wanted to be thought of as a poet." Now we can read why.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.