Sunday sessions with Franco

With over 2000 films watched, including some censored by his own regime, Franco's love for films has been confirmed

'Cinematograph Program to be screened before Their Excellencies on January 6, 1946. Noticiario español number 157-B. Imágenes number 53. Intermission. Immortal Sargeant, starring Henry Fonda and Maureen O'Hara. Director: Jhon (sic) Stahl. Production and distribution: FOX.'

'With this kind of pomp and circumstance, the Palace of El Pardo, Franco's regular residence, announced its first known film screening. These screenings would become regular events for over 30 years until the dictator's death, and prove that cinema was one of his great passions.

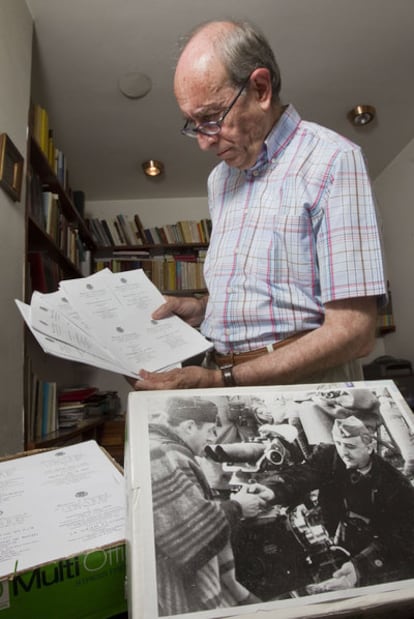

While searching for information that would prove that Francisco Franco worked as a film critic (using a pseudonym) for a military magazine, film history professor Josep Maria Caparrós Llena one day came across information about El Pardo's habitual film screenings. The archives of the dictator's residence yielded fascinating study material that confirmed the urban legend regarding Franco's passion for the movies: in the last three decades of his life, he watched 2,094 feature-length films in private sessions that were also attended by his wife, a few relatives and a select group of friends.

"It is a bottomless pit that will tell us a lot about the tastes and habits of Franco, the movie buff," says Caparrós, a member of the Film History Research Center of Barcelona University's Geography and History School.

Records show that El Pardo screened an average of two movies a week, one of which was always shown on Sundays. August was the only month with no movies during the entire 31 years of home cinema sessions.

The ritual was faithful to the customs of the era. The screenings always took place in the afternoons, inside the Teatro de los Reyes hall, and they always began with the newsreel Noticiario español, popularly known as No-do, which highlighted the regime's triumphs. Caparrós has yet to review these programs: "It is very possible that they showed him mostly the ones in which he appeared personally." That would not be very difficult: the dictator appeared 1,376 times in the sadly biased news reports - 34.2 percent of all No-do programs ever produced.

The newsreel was sometimes complemented - or occasionally replaced - with Imágenes, monographic reports produced by the same people who made the No-do. On January 11, 1950, no fewer than four of these documentaries were shown, including one about sport fishing for salmon. After these came an intermission, followed by the featured movie."That means that he spent over half an afternoon, twice a week, watching movies!" exclaims Caparrós.

The scholar believes that the programs were put together by Franco's friend, the film producer Cesáreo González (of Suevia Films), and by his own wife, Carmen Polo. "For Franco, movies were a hobby, a way to kill time, and that explains why most of what he watched was commercial fare, including lots of comedies, very few musicals and quite a few westerns and adventure movies." Lacking a more in-depth study, it is possible to establish some percentages: around three quarters of what he watched (1,500 films) were foreign productions, the majority of which were "from Hollywood; there is very little European cinema and I haven't found any Russian movies," says Caparrós. There are just 500 Spanish movies in the screening programs, but there are plenty of James Bond (including From Russia with Love), and The Ten Commandments; Ben-Hur; The Godfather and Cabaret. There are only three Hitchcock films.

Franco watched everything dubbed into Spanish, and the number of cult movies he watched during the entire three decades can be counted on the fingers of both hands: Bergman's The Virgin Spring, Fellini's Nights of Cabiria, Joseph Losey's The go-between; Visconti's The Leopard and Ludwig, and Kurosawa's Rashomon.

To a much lesser extent, El Pardo also screened uncensored movies, representing less than 0.5 percent of the total. But Caparrós has found one that was specifically on the forbidden list: Cristóbal Colón, by Fredric March, which Franco watched in 1950. On January 12, 1947, he also watched Casablanca, despite its references to the Spanish Civil War. With the passing of the years, the scholar suggests, "the movies got harsher."

"There were those by the Communist director Juan Antonio Bardem such as Muerte de un ciclista, Calle Mayor and Cómicos, and other pretty controversial ones like Furia española, Pepita Jiménez.

"The reels were sent over to El Pardo by the distributors themselves. "Courtesy of Walt Disney, to be screened for Their Excellencies," read the card for the session of January 26, 1952, which featured the animation film Cinderella. Cartoon films were a must in the special sessions that Franco organized on or around the date of his granddaughter María del Carmen's birthday. On February 26, 1955, there were no fewer than seven animation films shown, including The Adventures of Tom and Jerry. The dictator was very interested in animation, and possibly produced homemade cartoons himself.

There was another very special session on December 3, 1950, when the No-do presented Marcha nupcial (coverage of Franco's daughter's wedding) and images of a trip to Italy taken by his wife, Carmen Polo, which shows that she had cinematographic ambitions of her own.

The logistics of carrying the reels to and fro were handled by No-do personnel, who also operated the film cabin. "There were never more than three people: Carlos Suárez, Antonio Ravenga (both deceased) and Jorge Palacio, who is still alive but very elderly," says Caparrós, who believes that Franco must have also watched more "delicate" films alone. He suspects this because among the 2,094 feature-length movies that were screened, there were two by Berlanga: Welcome Mister Marshall! (which he saw before its release, on February 10, 1952) and Calabuig. There are no records, however, of El verdugo (The Executioner), which "he watched and which bothered him excessively." Something similar happened with Buñuel's Viridiana.

In 1954, the Franco family saw the most movies - a total of 79. Beginning in the 1960s there was a slowdown, which Caparrós attributes to the rise of television. Even so, in 1975, the year of Franco's death, El Pardo still screened 44 movies. In the last session, on October 26, less than a month before his death, the documentary shown was Pasaporte para la paz, and the film was Verdict by André Cayatte, starring Sophia Loren and Jean Gabin. A cinematographic wink?

Pius XII, secret spectator of 'Raza'

There is no doubt that the most singular spectator of Raza, the movie based on a text written by Franco using the pseudonym Jaime de Andrade, was Pope Pius XII. The film was screened at the Vatican in May 1942. The leader of the Catholic faith liked the story about good believers (members of the clergy and Francoist troops) and faithless bad guys (republican militias), set in the Spanish Civil War that Franco was so familiar with.

"He was greatly pleased by the high spirit that characterized it, even though he only watched the scenes with the greatest religious and dramatic emotional intensity," wrote Ambassador José de Yanguas to the foreign minister on May 9, 1942. But the pope's heart and Vatican diplomacy were two different things. The ambassador warned in his letter that Pius XII wanted to keep his attendance a secret: "It is his wish that this should not be publicized, being an exceptional case."

The document was reproduced by Magís Crusells in the study Franco, un dictador de película (Franco, a dictator of film), included in the book Vidas de cine (Lives of Cinema). Crusells, who is the secretary of the Film History Research Center at Barcelona University and a professor at the Instituto Palau Ausit in Ripollet, has followed the international trail of Raza, which was heavily conditioned by the political alliances of the new dictatorial regime.

The movie found no obstacles in Italy, and competed in the Mostra de Venecia, after which it was distributed by Bassoli Films under the title Le due strade. In exchange, Spain authorized the import of eight Italian movies. In Nazi-controlled territory, however, things were not that easy. The director of Raza, José Luis Sáenz de Heredia, went to Berlin in February 1942 to obtain permission to screen the film to the Blue Division, a group of Spanish volunteers who fought in the German army during WWII. It was Franco's personal desire that it should be so, but the German army shot it down: they did not want any civilians in military areas. Nor was it an easy job to negotiate the film's screening in Germany "due to a lack of interest in it and because the war was not going as favorably for them anymore," explains Magís Crusells. Finally, in exchange for showing 10 German movies in Spain, Raza was screened in 218 German movie theaters and sold in several European countries. Sweden and Romania rejected it on the grounds that it was "a propaganda film that could cause public protests that would disturb the peace."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.