"I don't know what people think of me outside Brazil"

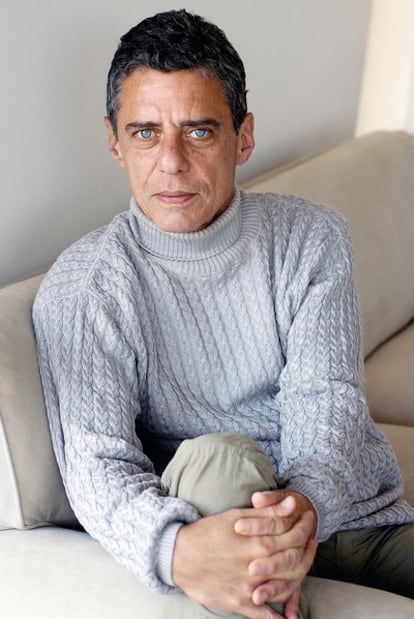

Chico Buarque is a great Brazilian icon. For more than four decades he was known primarily for his music, but Francisco Buarque de Hollanda, 66, was not satisfied being one of his country's most important musicians, a legitimate son of bossa nova, a political reference during the hard times of the dictatorship and a soccer player who has not missed a game with his team in the last 30 years.

He also wanted to express his creativity through literature, to prove that he could become a respected writer. And he has gained that respect not just in Brazil but in the entire world. His eighth novel, Leite Derramado (or, Spilled Milk), has just been published in Spain. His earlier work, Budapest, picked up awards, and France's Le Nouvel Observateur described him as one of the most interesting contemporary authors in the Portuguese language.

Question. At first it seemed like they wanted to launch you as a pop artist of 'bossa nova'. Did you not fit into that?

Answer. It wasn't like that. I had a bad experience when I was living in Italy, around 1969. Back then Brazilian music was not very well understood, plus they thought I was a pretty boy.

Q. Good-looking. Just like now. That could even be a defect.

A. Perhaps that is why, outside Brazil, they wanted to brand me as a pop musician. I didn't understand what was going on in Italy. I don't know what people think of me outside Brazil. I don't have an international career. I lived in Italy for political reasons [spending 18 months in exile during the Brazilian dictatorship], but nearly my entire career developed here. With literature it's different ? translations, everything, it's easier to make yourself understood. In music, things can be interpreted in any way. And more so with Brazilian music because it's got a bit of everything mixed in, and you don't quite know whether it's samba, bossa nova... It's everything at the same time.

Q. As a writer, you've embarked on very curious experiments. You wrote Budapest without ever having been to the city. Did you visit it afterwards?

A. I had never been there, and I didn't want to go. I began writing and I was fascinated by the [Hungarian] language. I wasn't interested in learning anything beyond that; studying Hungarian would have taken 10 years. But it turned out better this way: a diffuse city, a story enveloped in mist. It was very interesting arriving in Budapest after having been there in a way. I never wanted to pretend that I knew it well; the names were made up, based on the Hungarian soccer side. To admit that I had never been to the city created mistrust. Some took it well; others, frankly, did not.

Q. You were not in Budapest, but in Leite derramado you know your way around. You talk in depth about Brazil.

A. But I was not alive during that period.

Q. Each of us has lived in the past of our homeland somehow. Don't you think ancestors build our identity?

A. In a way, writing about something that happened 100 years ago is like not knowing the place. You are lost in time and space. The idea for Leite derramado began with that premise. I did more research for this book than for Budapest. Besides what I read and what I heard, there were the stories from my mother, who died barely a year ago at age 100.

Q. But this old Brazil you portray in Leite derramado, has it disappeared?

A. It persists in many people's mentality, their ideas about the old country with its former owners, the holders of power, the owners of the money, the perplexity in the face of a new growing country, the inability to admit that the country will belong to other families, to other classes. They were clans with feelings of possession and they observe people who prosper with mistrust [...] Yesterday I read a newspaper story that made a difference between the rich and the very rich of Santa Catalina. The rich normally go to the beach, while the very rich stay inside their luxury hotels, alone with their prejudices against the merely rich.

Q. So the middle classes have landed in Brazil and they want others to sit up and take notice?

A. I no doubt prefer this Brazil to the old one. It is more dynamic.

Q. How much credit should [former president] Lula get for that?

A. A lot.

Q. Did he really undertake a historical transformation?

A. Yes. His priority was pulling the greatest number of people out of poverty. This continues with Dilma Rousseff. The social situation in Brazil was shameful, plagued with inequalities and all that flaunted wealth. But credit must also go to the economic policy foundations set up by Fernando Enrique Cardoso. That was the key that allowed for progress. This entire transformation was carried out under the rules of capitalism to create a wealth that had to be distributed. Some on the left may feel that it was not humanitarian enough, but nobody can deny that it was the most intelligent method.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.