The unseen correspondence of Mauthausen's 'Dr Death'

EL PAÍS reveals the letters sent by Aribert Heim while in hiding

Dear Gerda. You must get in touch with the Thyssen family so they can confirm that in the summer of 1942 I spent a few weeks or maybe two or three months there - I cannot remember the precise amount of time. I am sure the people who were young back then and are now my age can remember... I wish you good health. I suppose that is the main thing. Greetings to everyone."

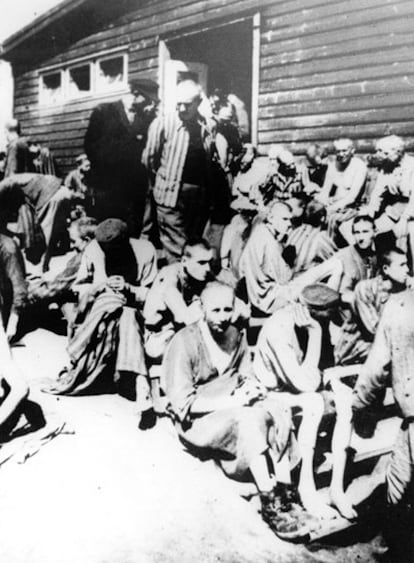

Aribert Heim, widely known as "The Butcher of Mauthausen," wrote this letter on October 15, 1982 from his hiding place in Cairo, Egypt, where he had fled 20 years earlier. He was wanted by Germany's justice system for murdering 300 prisoners with benzene injections to the heart inside the sinister Revier, the infirmary at the concentration camp where he worked as a doctor for the SS. The objective of the Nazi was to prove that he was in Mauthausen in 1941 and not in 1942, as several witnesses have claimed.

Heim was wanted for killing 300 prisoners with injections of benzene to the heart

His son visited him secretly, but denied knowledge of his whereabouts

The doctor crammed his letters with philosophical messages about life

"He injected magnesium chloride and caused their immediate death"

"Dr Death," the son of a policeman and a housewife from Austria, was arrested after the war and subjected to a de-Nazification process inside a salt mine under Allied control. He was released in 1947 and a year later he met his future wife Frield, a doctor from a wealthy German family. In 1955 the Heims settled down in the small palace owned by his in-laws in Baden Baden, Germany, where they worked as gynecologists. There they lived peacefully for years, until witnesses started to emerge pointing him out as one of the Mauthausen criminals. A policeman came to the house to enquire about his past, which prompted him to flee in 1962. It was at this time that the Auschwitz trials were taking place in Germany.

Both the Thyssens and Frield's family had homes in Lugano, Switzerland, and like many other influential clans, they took in SS officials during the war. "At the time, it was an honor to have a German soldier staying in your house," says Rüdiger, Heim's son, as he prepares a cup of coffee at the family mansion in Baden Baden, where he lives with his 88-year-old mother.

The late Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza - husband of Tita Cervera and patron of the arts, who created the Madrid museum that bears his name - and his cousins were most likely the young Thyssens that the Nazi was referring to in his letter. The future baron was 21 years old at the time Heim claims to have stayed with the family.

Doctor Death sent his relatives 21 handwritten letters - to which EL PAÍS has had access - and which were handed over by his son Rüdiger to the judge in Baden Baden who is investigating the Nazi's alleged death in Egypt in 1992. The circumstances of his passing remain a mystery, as the body was never found. "These [letters] are further proof that my father lived there," says his son, who visited Heim secretly and until recently denied knowing anything about his whereabouts.

Gerda, the person who was tasked with getting the Thyssens to plead on Heim's behalf, was in fact his sister Herta, the family member who helped him most during his years as a fugitive from justice. She was an elegant, attractive woman with a hectic social life, who moved in German aristocratic circles and was a frequent visitor to the Thyssen mansion in Munich. "It would be enough to get confirmation, I'm talking about the Von Thyssens; this would be easiest since you were there too, and they can confirm that we were there in the summer of 1942 for two or three months... If you can get the Thyssens' confirmation, I could add it to the analysis of my testimonies and send it in."

Between 1978 and 1985, Aribert Heim addressed most of his correspondence to Herta. The letters were filled with secret codes, cryptic sentences and messages in which he asked for money, occasionally criticized his ex-wife and children, and demanded that she locate witnesses or "non-Zionist" Jews to help defend him from "the horrible horrors" that several former Mauthausen inmates were accusing him of. None of the letters reveal the slightest note of self-criticism or contrition.

When he prepared his letters, Dr Death used a dark red notebook that he bought in Egypt; inside he wrote down the names of 12 people in code, to ensure they would not be identified if the police should get hold of his correspondence. Lyda was in fact Hilda, his other sister; Dora was his ex-wife Frield; Gretl was his young son Rüdiger; Rainer was his lawyer Steineker; Lattle was Simon Wiesenthal, the Nazi hunter who had been a prisoner at Mauthausen and who followed Heim's trail until his own death; and there was also Carola, a friend.

Heim's letters are penned in blue ink; his handwriting is small and slanted to the right. The doctor, who was accused of extracting his victims' organs and using their skulls as paperweights, crammed his letters with philosophical messages about life, health and happiness: "The struggle for life must be taken in good sport, no matter what;" "You only live once and must not forget about humor." "Remaining calm is good for your health, which is the main thing in life," he would tell Herta when she was separating from her womanizing husband.

The 21 letters reached their destination from Cairo thanks to the security system devised by the Nazi criminal. They were always addressed to a couple who lived in a small Bavarian town, and these friends traveled personally to Frankfurt to deliver them to Herta by hand. For her part, she always replied while she was abroad on vacation or visiting friends in other countries.

On July 26, 1979 Heim wrote a long letter to Lothar Späth, the minister-president of the land, in which he criticized the fact that authorities let the weekly Der Spiegel access the reports of a Berlin court. The Nazi asserted that he was in Mauthausen for seven weeks, between October and November 1941, and that the legal proceedings to seize a 34-storey building in Berlin from him were based on the testimony of Otto Kleingünther, who said that Eduard Krebsbach - the senior SS doctor at Mauthausen - gave an order in April or May 1942 to inject benzene into the prisoners and extract internal organs without anesthetic. "I cannot be held responsible for events that took place in 1942... The terrible horrors I allegedly performed on the prisoners, extracting their organs, could only come from the fantasies of a fanatical Zionist... Wiesenthal's personal brand of justice is funded by the US Zionist lobby," he said. Heim was eventually fined 510,000 German marks, the value of the building that was seized, and he was accused of murdering 300 prisoners during his stay at Mauthausen.

The criminal prosecution against Heim was led by Commissioner Aedtner, who spent his life on the Nazi's trail. Aedtner searched the world for witnesses; he unsuccessfully looked for nine former Spanish prisoners of the 26 who were operated on by Heim in 1941, according to the Red Cross' surgery records. Eight of them died in Mauthausen and nearby Gusen, while another five died shortly after the operation.

Aedtner did locate the former prisoners Lotter, Hohler, Kauffman, Sommer and Rieger, who described the crimes that the accusation against Heim is based on. According to them, the prisoners he selected for physical elimination were incapable of working or gravely ill, the attorney wrote. "Also healthy young Jewish prisoners got special treatment. With the cooperation of prisoner-workers [kapos] and other assistants at the Revier [infirmary], he administered an ether anesthetic to simulate a medical examination. In this state of defenselessness, he personally injected magnesium chloride in the ventricle and caused their immediate death. The exact number of victims is not known because no records were kept." According to the attorney, Heim was acting out of his own free will and his operations "surprised the health personnel, who were already accustomed to inhumanity."

In his letters, Heim describes himself as a very different person from the monster portrayed by his victims, and even as a benefactor of Jews and sick people, whom he allegedly helped after the war. "During the war I helped Jewish acquaintances as much as I could, as proven by the letter of Dr Pauline Kachelbacher, which was presented as evidence during the de-Nazification process in 1947."

In his letter to Minister Späth, the SS medic calls the prisoners who denounced him "ex-criminals" and provides a peculiar explanation of his flight: "In 1962, I not only went abroad because of a spinal injury, but also because I needed to prove my innocence in case of a trial [...]; also because of my six- and 12-year-old children. Their school was next to the penitentiary and the courthouse, which would have prevented them from staying on if I'd remained."

He concludes his letter by depicting himself as a benefactor. "I lost eight years to war and prison at the service of the State; I later worked for a pittance in clinics and hospitals, doing gynecology night shifts, so I can rightfully say that I have performed Christian deeds all my life for the good of my fellow man."

On October 26, 1979, Aribert Heim also wrote to his Jewish friend and schoolmate, Dr Robert Braun, to ask him to plead on his behalf. Regarding his period in Mauthausen, he said that he arrived there "as a troop doctor, yet had to work in the infirmary with the prisoners, and this has now become the focal point of my life... Later came the testimonies, mostly from Communists."

Dr Death told his colleague about the horrors that the witnesses attributed to him - liver extractions, lethal injections to the heart - and added: "As you can understand, a doctor would never have done something as senseless and beastly as that." He failed to mention that other SS doctors had perpetrated similar crimes at Mauthausen.

"Perhaps you have some influence in non-Zionist Jewish circles who criticize Wiesenthal and they can offer some helpful advice. I want to face this thing like a good sport and I don't want to give up. I don't want these accusations to destroy the end of my life. Thanks for your help. You will soon hear from my sister," he wrote. Braun sent a notarized letter, although years later he qualified his support for Heim.

Besides the Thyssens, Heim asked his sister to find Dr Rieger, the assistant at the Mauthausen infirmary and one of the five witnesses against him. "Do not offer him money so as not to lead him into false testimony. He is the most decisive [person] in the case - he said positive but also negative things, especially about the injections, which is something totally new to me and which may have taken place after my stay there, since during the euthanasia period things worked differently," he wrote in a letter dated November 26, 1979.

Heim's letters occasionally reflect acerbic criticism of his ex-wife and children for their lack of self-esteem and their tight-fistedness. In a letter he wrote to his former partner on August 14, 1982 he wrote: "I ask that you tell me whether you got my letters from the fall of 1980 or not, because you have taken the liberty of not writing to me since January 1980. I also asked for my family to send me 6,000 francs a year, 500 francs a month; if each member of the family put aside 125 francs every month, which would not be too much of a sacrifice, the annual transfers would be easy and I would not be this concerned... I saved money all my life so my children could have a home here [he had bought a plot in Alexandria to build four apartments]. I don't think it's too much to ask if I get from my family something of what I saved in Germany."

Heim's life in Egypt remains an enigma, since his letters afford no information about his activities. "Too bad you don't have a distraction to keep you busy," he wrote to his sister Hilda. "I have so many things that interest me here, that if the day had 28 hours it would still not be enough to do all that I have to do."

"My father took photographs of sportsmen, read medicine articles, listened to the BBC, studied Arabic and repaired the Domas' [his landlords] bicycles," said his son Rüdiger.

Heim's correspondence ended in 1985. From then and until his alleged death in 1992, the fugitive contacted his sister and son through a telephone owned by Naghy, his Egyptian business partner. When Hilda died, the police came to the cemetery, thinking that the fugitive would show up at the funeral.

In a recent court statement, Rüdiger told the judge that his father died in his presence in the summer of 1992, at the age of 78, inside his hotel room on 414 Port Said Street, Cairo, of colon cancer. He said that, following his father's wishes, he donated the body to a hospital for scientific research, but that years later, when he returned to Cairo, he realized that his wish had not been respected. Rüdiger said he does not know which cemetery for anonymous people he was buried in, and refused to provide a sample of his own DNA.

The German justice system is waiting for Egyptian authorities to respond to a request for legal assistance and is examining documents that Heim kept in the hotel where he lived in Cairo. The Domas have backed Rüdiger's version, but the body is still missing.

"They do not want to accept the fact that he's dead," complains Rüdiger in his home in Baden Baden. The Heim family has asked for the case against Dr Death to be closed, but neither the judges nor the police are ready to shut the investigation into the most wanted Nazi in the world, who, if he were still alive, would now be 95 years old.

"Lead a hygienic life"

Aribert Heim once made a recommendation to his youngest son, Rüdiger - that he should travel to Spain to study. It was a country he knew well, judging by the letter he sent him from Cairo on December 31, 1985.

"I can give you information about Spain and I recommend that you buy a second home there, because you can really feel at home thanks to all the tourists, as well as the hospitality of the country, which also knows how to appreciate money."

When Heim fled in 1962, he drove from his home in Baden Baden, traveled across France and spent a few days in Barcelona, where he ate regularly at a restaurant called Los Caracoles, which he also recommended to his son some years later.

During his period as a gynecologist, Heim was in touch with the Spanish doctor V. Salvatierra, an adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Valencia Medicine School, as revealed by a thank-you card sent by the latter in July 1954.

One particular letter from the fugitive to his son ended on a very personal note: "Lead a hygienic life, and during new encounters use a condom, because AIDS can be passed along by anyone. Better a good dinner than an uncertain alliance. Have a good New Year's and send my greetings to everyone."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.