"I didn't know where I was... I heard people crying and screaming"

Witness testimony contradicts the official line of Moroccan authorities in Laâyoune

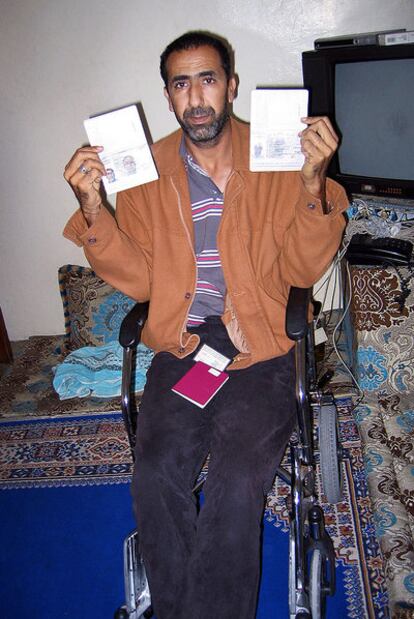

Lasiri Salek says that he was inside the Agdaym Izik camp on November 8 when Moroccan police dismantled it, and points at the bullet hole in his left arm. Ahmed Guacharo Baillie walked into the police station in Laâyoune on November 9; by the time he came out three days later he could no longer stand on his own legs, and is now in a wheelchair.

Both testimonies contradict statements made last Sunday by the governor of Laâyoune, Mohamed Jelmouss, to journalists in the capital of Western Sahara, the disputed territory that has been under Moroccan control since Spain walked out of its former colony in the mid-1970s. Jelmouss said that the police had not used firearms during the assault on the Sahrawi protest camp, nor during the subsequent repression. He also denied any torture at police stations.

"I told them I could neither walk nor move but they replied: 'So die then'"

Although journalists are now allowed in Laâyoune - there was a news blackout during the confrontation and Spanish reporters attempting to enter the territory were forcibly turned back - their work is seriously hindered by police surveillance.

This has prevented a face-to-face meeting between EL PAÍS and Lasiri Salek. Like other Sahrawis who were wounded at Agdaym Izik, he remains in hiding, and did not even dare go to a hospital. Instead, he made a video with his statements and sent it to this reporter through a trusted aide. On screen, the 29-year-old Salek shows the bullet entry and exit points on his left forearm, and says that a friend of his was shot twice in the shoulder and the leg. "Many people in the same situation as me were left lying in the camp," he adds.

Ahmed Gachbar Baillal, 38, did agree to talk face to face, even though three police officers followed this reporter to his door. "I know that when you leave they will interrogate me back at the station, but I am not afraid," he said, sitting in a wheelchair in his home in the Laâyoune neighborhood of Colominas Nueva.

Baillal, who has a Spanish ID card, explains that eight policemen armed with machine guns arrested him inside his home on November 9, blindfolded him, tied his hands behind his back and took him away in a car. "I didn't know where I was. I heard people crying and screaming around me," he says. He was beaten with sticks and belts for hours. The next day, an officer kicked him between the kidneys and he fell to the ground. "I told them I could neither walk nor move, but they replied: 'So die there.' They removed the blindfold and I realized I was at the police station next to the wilaya [seat of local government]. Four policemen grabbed my arms and legs and took me to see a high-ranking official, who told me to leave. I insisted I could not move and I asked for an ambulance, but he refused. He said: 'You want to get out? Never talk about what happened here, or I will take you to a place where you will never see the light of day.' They left me lying in a room."

On the night of November 11, the official returned. "If you don't walk, you won't get out of here." He asked to be taken outside and put in a taxi. That is how he got home. "My brother took me to Ben Mehdi hospital, but the police did not let me in," he says. The next day he went back, but a doctor told him that the X-ray machines were not working. His family then took him to a private doctor, who examined him and said his lumbar area was damaged. "He says I can't move in a month, and then we'll see."

Spain's government has been upbraided by sympathizers of the Sahrawi cause for its reluctance to condemn Morocco's actions. It has justified its stance by saying good bilateral relations with Rabat are of foremost importance.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.