Jan Martínez Ahrens, EL PAÍS editor-in-chief: ‘Artificial intelligence can never replace journalists on the battlefield’

A group of the newspaper’s subscribers attended a meeting with its top editorial director in his first public event since being appointed

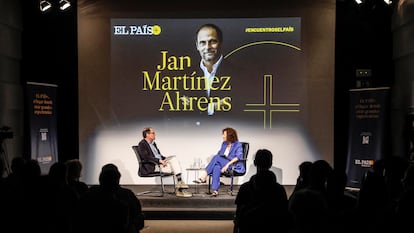

Fifty of EL PAÍS’s more than 426,000 subscribers arrived at the newspaper’s Madrid headquarters last Friday afternoon for a meeting with its editor-in-chief, Jan Martínez Ahrens. “You are the true owners of our information and the newspaper,” he said by way of welcome at his first public event since taking over as the newspaper’s editor-in-chief at the beginning of June.

During a conversation with journalist Ana Fuentes, he stated: “Although we are facing a disinformation crisis, major newspapers are living in a powerful moment. The weapons that technology provides us can help us, including artificial intelligence, which can never replace journalists on the battlefield.”

Martínez Ahrens was, of course, referring to war coverage. For example, EL PAÍS contributor Mohamed Solaimane is covering the war in the Gaza Strip, the deadliest place in the world for journalism today. “What he’s seeing there can’t be reproduced by artificial intelligence. It’s quite another matter that certain news stories about the stock market could be handled with this technology, with readers informed of its use.”

The EL PAÍS editor-in-chief extended this contrast between journalism and the threats of artificial intelligence to other fields of reporting: “You need the source. The documents. That which takes you out of the normal flow of information.”

He also recalled the complex process of producing the joint exclusive with The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, and Der Spiegel that this newspaper published in collaboration with WikiLeaks in 2010. That Cablegate revealed 250,000 confidential U.S. State Department documents that shed light on various cases of corruption, diplomatic scandals, and espionage entanglements on an international scale.

Martínez Ahrens told the newspaper’s subscribers that the scoop was of such magnitude that, in the end, the entire newsroom was involved. It began with his conversations about Julian Assange with EL PAÍS journalist Joseba Elola, who at the time was part of the Domingo supplement team directed by Martínez Ahrens. Those talks led to a months-long effort to establish contact with Assange, marked by several key milestones. Once a channel was opened, a series of in-person, secret meetings took place in Geneva. “We managed to convince Assange that EL PAÍS was the group he needed to make an impact in the Spanish language.”

U.S. politics remains a central focus of coverage today, with Donald Trump’s second term. Martínez Ahrens was chief correspondent in Washington during Trump’s first presidency, and he recalled that the first Trump — already dangerous and excessive at the time — pales in comparison to what we are seeing now. “He works for a far-right ideological base. And one of his objectives is to find an external enemy. Among them, foreigners. Especially Latinos and Mexicans. They are told they will be expelled without any rights, and the sad thing is that part of that community supports him. Our editorial line there is to oppose Trump’s immigration policies.”

In Spain, it is the political party Vox that is driving the far right’s growing momentum. Several polls over the past year have pointed this out, most recently the survey by 40dB. for this newspaper, which just days ago showed the party at its best level since the 2023 general elections. For Martínez Ahrens, it is especially worrying “that a movement with roots in the terrible memory of a dictatorship born of bloody conflict and the killing of civilians for defending democracy could now be gaining strength.” He linked the rise of Vox to “extreme polarization and the use of verbal violence by politicians, which legitimizes it.” In the face of this trend, Martínez Ahrens said the newspaper must serve as a point of reference. “I believe it has done so for the past 50 years.”

To continue on that path, he said, the formula is to return to the values that inspired the creation of EL PAÍS nearly half a century ago, when it was founded to defend a democracy in Spain that had not yet been born. “At a time of such radicalization, we must prioritize reflection and quality information. We cannot be militants of any political party, but we can be militants of many causes. To be a newspaper that calls for reflection and for the values of democratic consensus, that is plural and independent. That is part of our founding values. The media climate in Spain has become very tense. There are outlets that practice militancy. We are progressive — we have been and we always will be. And we are so honestly,” said the editor-in-chief of EL PAÍS. He added that independence exists because truth exists: a journalist may have their ideology, but if they stick to facts, verification, and contrast, “the truth prevails.”

Regarding the practice of journalism, he stressed that “journalism is method and transparency.” He added: “It can make mistakes, but if that happens, it must correct them and explain how the error occurred. One of the advantages of our newspaper is that we are required to follow the journalistic method laid out in our Style Book. And we have bodies that enforce that obligation, from the Editorial Committee to the Readers’ Ombudsperson.”

EL PAÍS journalist Ana Fuentes of this newspaper asked Martínez Ahrens whether a change of editor-in-chief also means a change in the editorial line. He replied that the editorial line of EL PAÍS has been set since its founding. “Sensitivities and interests change — and I have some to which I pay more attention.” Fuentes also mentioned his reputation for being demanding. “There are worse reputations,” said Martínez Ahrens. “This is not an easy newsroom. We tend to be very self-critical. Our successes don’t last long, and we punish ourselves a lot. Better to be demanding and keep the light on at any hour to fulfill our duty, which is to inform.”

Next May 4, the newspaper will celebrate its 50th anniversary. Looking back, its editor-in-chief believes that the values to continue defending are those of consensus and democracy. “And a call to listen to others in a society that is somewhat ideologically militarized. EL PAÍS has also been tremendously attuned to social progress. When I was head of the Society section, we championed the fight against gender violence — once wrongly called crimes of passion — and the evolution of divorce and same-sex marriage.”

Today, according to Martínez Ahrens, issues such as gender, equality, and reducing economic disparities remain key concerns. “We must know how to redistribute wealth, and also how to create it,” he noted. “We are still a very unequal society, where young people cannot afford to buy a home or a car. That is a message that reaches many, and they interpret it as meaning they do not belong in this society, paving the way for anti-politics.”

One subscriber wanted to know how long the print edition of EL PAÍS would last after its 50th anniversary next year. Martínez Ahrens replied that he “predicts a good future for it, although its demise was predicted many years ago.” He added: “I have good news for the print edition. Its sales have dropped significantly, but the downward trend is beginning to soften. And it has a type of reader who, for me, is premium. I give it, at the very least, many decades of life ahead of it.”

Another subscriber, a self-proclaimed “geek reader” who has a copy of the first edition of EL PAÍS from May 4, 1976, asked his opinion about coverage of crime and accidents, a field in which he once worked. “You can reflect real sociology through those stories if you avoid the terrible path of sensationalism.”

For another subscriber, the question was whether journalism can still be considered the fourth estate. “For me, power is influence,” Martínez Ahrens replied. “Being able to convince people of things we know to be true. For example, having conveyed the horrors in Gaza or the threats to democracy in Latin America.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.