Is it your bank or a scam? How to deal with phishing attacks

Follow these simple steps to avoid falling for emails and text messages from cyberattackers that pose as banks and shipping companies to defraud the recipient

The email may seem genuine, and the link that it includes hard to resist: a package held at customs, a notification from the bank about a credit card charge... perhaps even a prize that we won. Phishing cyberattacks are a real threat, one that takes advantage of the weakest link in the chain: humans.

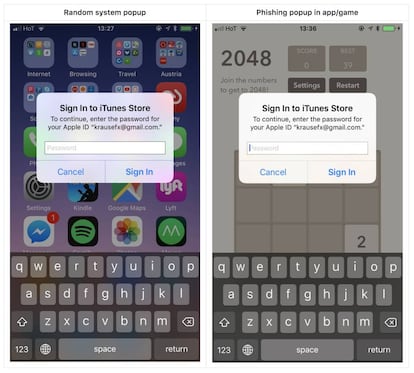

The scam works through deception. The attacker creates emails or text messages that look virtually identical to the ones from the company they’re trying to impersonate, usually urging the recipient to either click on a link or open an attachment; the former to harvest credit card or banking data, the latter to introduce some type of malicious software into the system.

AI to escalate the attacks

Regarding the amount and precision of the phishing attacks, prospects are not good. “Advances in artificial intelligence will cause a frenzy of identity theft,” explains Francisco Arnau, regional vice president of cybersecurity firm Akamai for Spain and Portugal. “Looking forward, we can expect that constant advances in artificial intelligence, such as those seen in systems like GPT-3, will make targeted phishing more compelling, scalable and common.”

These systems allow for the generation of “millions of email or text messages, each one tailored to an individual recipient, and each one with compelling human-like qualities,” Arnau continues. This will pose a significant challenge to existing anti-phishing technologies and “will make it much more difficult for people to detect suspicious messages.”

How to protect yourself against a phishing attack

The first thing to understand is that these attacks can target anyone. They make no distinction between individuals or companies, and are launched en masse – with devastating consequences for those who fall for them.

The numbers are overwhelming: it is estimated that approximately 15 billion emails of these characteristics are sent every day, of which a third are opened. This technique also accounts for 90% of all security breaches in the world. So how can you protect yourself against a phishing attack?

Suspicion is your greatest ally

“When you receive a very tempting offer, it’s better to doubt,” explains Fernando Suárez, president of the General Council of Official Colleges of Computer Engineering in Spain. This expert appeals to the most important protection barrier, one that can save the user from serious consequences. “A bank will never ask us to change the password through an email or by clicking on a link.”

Kevin Mitnick, a well-known former hacker, explains to EL PAÍS that “people tend to be trusting unless they have already been the victims of a cyberattack, or if they have been taught about the threat of phishing.”

Never click on a link, and ask before opening an attachment

All phishing attacks include one of two essential elements: either a hyperlink or an attachment. The goal of the attackers is to obtain valuable information from the recipient (to have their way with their checking account or credit card) or to install malware with even worse intentions.

“If you receive a hyperlink and it makes you doubt, it’s best to type by hand the URL of the company it claims to be from,” points out Suárez, alluding to the fact that those links are usually maliciously manipulated. The general rule, in any case, should be never to click on a link or open attachments that come in an email. For the latter, the recommendation is to contact the sender by other means to verify the source of the attachment, be it with a phone call, a WhatsApp message or a text. But never responding to the email.

Take a look at the “From” field

Cyberattackers are becoming more sophisticated when it comes to crafting emails, but they cannot always camouflage them entirely. One clue to detecting the deception lies in the domain of origin: if you come across senders with domains like “microsoft-support.com” or “apple-support.com” (similar to the authentic ones, but not quite), you are looking at a phishing attack. In any case, and when in doubt, it is best not to interact with that email.

The same applies to text messages, explains Suárez, who warns of an additional risk: on mobile phones, we are less cautious and act more impulsively than on computers. Shipping companies are collateral victims of cyberattacks, especially during periods of high activity, such as Christmas. A mysterious message demanding the payment of a customs charge for a package will be phishing in disguise: “a bank or other large entities will never demand an immediate payment via cell phone,” explains Suárez. The problem is not so much the payment, which is usually low, as the fact that when you make it, you are handing your credit card information to scammers.

What time was the message sent?

Mitnick’s experience in this area is invaluable. The expert provides a telltale sign that can help identify phishing: the time the message was sent. Be wary of a message sent before sunrise demanding a payment or a reply. Internet users usually associate with environments in their own time zone, so any activity outside of it should be cause for suspicion.

In the same way, the “Subject” field can be a sign of an email’s intent: Is the language too informal? Do they address you by your email address instead of your name? In addition, if the subject field shows a “Re:” indicating a reply to an email that you never sent, you are seeing another camouflage technique used by cyber attackers.

Beware of requests for urgent action

Another technique hackers use when carrying out a cyberattack is conveying a sense of urgency. This is evident in the messages in which alleged shipping companies warn you that you have a few hours to pay a fee or a package will be returned. These kinds of companies do not usually send these types of messages, and in any case the first step you should take in this situation, if you want to confirm the veracity of the message, is to contact them by another means.

Your guiding principle should be to “never click or enter your username and password in a conversation that you didn’t start; a simple rule that everyone should follow,” states Mitnick.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.