Feuding heirs, weak institutions and a mysterious will: Why didn’t the Gelman collection stay in Mexico?

The transfer to Spain’s Banco Santander of one of Mexico’s most powerful art collections, filled with works by Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, is the latest chapter in a long story full of intrigue and controversy

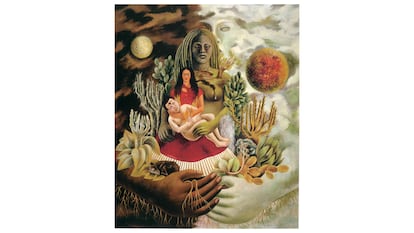

Natasha Gelman once had five Frida Kahlo paintings hanging in her bedroom. The most special one was a small portrait of Natasha herself, just a bust with a pensive expression and her hair pulled back. It was quite different from the one that Diego Rivera also painted of her, in which she posed in an evening gown reclining on a sofa with lush lilies in the background—a commission from her husband, Jacques Gelman, to the icon of Mexican muralism. During the second half of the 20th century, the Gelman couple were among the most influential figures in international art collecting, thanks to the fortune they amassed as producers during the golden age of Mexican cinema, including their friendship and lucrative partnership with Cantinflas.

Upon her husband’s death, their splendid European collection (comprising 81 works by Bacon, Dali, Picasso, and Matisse) passed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Mexican collection has just left for Spain, on loan to Banco Santander, after decades of touring the world, fleeing a legal battle among heirs. Natasha’s supposed wish for the collection to remain in Mexico, expressed in a will that no one has been able to verify, could not be fulfilled. This move has caused a stir in the country, which also has strict heritage protection laws. The government has taken action, announcing that part of the collection will be exhibited temporarily this spring in Mexico City, as the first stop on an international tour. But behind this latest chapter lies a long story of mysteries, intrigues, and twists more akin to a thriller.

The mystery begins with the two wealthy collectors. It was said that he came from a family of landowners in St. Petersburg, that he had studied in Paris, and that he owned jewels belonging to the last Russian tsar. It was said that she was born in Moravia, in what is now the Czech Republic, and that they both left Europe separately, fleeing World War II. They met in Mexico, and it was love at first sight. They married in 1941 and never returned. Jacques started a production company and made a fortune exporting and distributing films to the American market, using a young Cantinflas as a draw. It was there that their collecting began.

The first, the most important, was always the European collection. The Mexican collection was initially more of an accessory, almost a whim of Natasha’s, which grew until it became another jewel in the crown. Luis-Martín Lozano, an art historian specializing in modern Mexican art, met her after she was widowed in the 1990s. “Jacques never thought that the paintings by Frida Kahlo or Rivera were as valuable as the Picassos or Matisses. But she loved the Mexican collection, which at first served more as a status symbol.” According to the historian, the couple didn’t arrive in Mexico with much money and constructed themselves as glamorous figures through the paintings. Hence, the commissioned portraits. The Rivera portrait from 1943, which depicts Natasha as a Hollywood star, is the one that launched the Mexican collection.

They entered the world of high society. Their homes in New York and Mexico City were famous for their parties with politicians, actors, businesspeople, and artists, who would get drunk amidst the paintings of Dalí or Braque that hung on the walls. They were at the top.

The villainous executor?

The first turning point came with Jacques’ death and the arrival of another key figure, the American curator Robert R. Littman. In 1986, with the European collection already at the Met at the couple’s express wish, Littman became Natasha’s chief advisor. Together they expanded the collection. “They’d had no children, and for Natasha the paintings were like her own children, especially after Jacques’ death, when she dedicated herself completely to them. She knew them inside and out. She owned 13 of Frida’s paintings and was always very generous; on more than one occasion, she lent me some for temporary exhibitions,” adds Lozano, who has worked as a curator in several Mexican museums.

Natasha spent her final years in a country house in Cuernavaca. After her death, Littman announced that the will stipulated he was the executor of the collection and that it should remain in Mexico. In addition to the deceased owner’s alleged wishes, several works in the Gelman collection were protected by a 1972 law requiring that the Frida Kahlo, Rivera, Siqueiros, Orozco, and María Izquierdo collections could only leave the country temporarily and with government authorization. “The Mexican painting collection is my responsibility. I will ensure it is not separated and that it remains in Mexico. Everything stipulated by Mexican law will be complied with,” the executor stated in an interview at the time.

Littman got to work, according to several sources familiar with the negotiations, and the option of housing the collection in a museum in Cuernavaca itself arose. Gerardo Estrada, director of the National Institute of Fine Arts (INBAL) between 1992 and 2000, first approached the executor about a possible public purchase. “It wasn’t possible because my superiors said there was no money. At that time, the price was around $200 million. So we explored the possibility of an alliance with a large company,” he recounts over the phone. Costco, the American supermarket giant, financed the construction of a museum specifically for the collection, the Muros Cultural Center, where it remained for almost five years.

Everything seemed to have finally settled, but Estrada recalls that “during those years, Littman lived with a kind of paranoia in case any Gelman heirs showed up.” And indeed they did. A distant cousin in New York, a half-brother who sold the rights to a Mexican lawyer, and even one of Cantinflas’ sons, who accused the executor of taking advantage of Natasha, who had Alzheimer’s, all claimed their share. “Lawsuits began both inside and outside of Mexico, and the INBAL decided to remove the collection from the museum. I believe that was a mistake, because with the full force of the State, the lawsuits could have been resisted,” Estrada adds.

The collection was returned to Littman, who decided to take it out of the country and put it on tour for temporary exhibitions in Europe and the United States. Amid the controversy, the executor’s image as the villain of this story began to grow, as he was seen as fleeing with the jewels entrusted to him. This newspaper has sought his opinion through his lawyer in New York, but there has been no response. He was accused of profiting from and dividing the collection. However, both the cultural official and the historian believe that Littman fulfilled his obligations.

In fact, the lawsuits never prospered, and experts believe that without this promotion of Frida Kahlo, the international boom in interest for her work would never have happened. “The collection didn’t disappear; the exhibition catalogs are there. It remained intact, as stipulated in the will, and Mexican law was followed.” The will is the great blind spot in this whole story. No one claims to have seen it, and the notary who signed it was shot and killed in the streets of Mexico City in 2013.

Confusion among collectors

Last week’s announcement that the Gelman collection will be transferred to Spain for Banco Santander to manage part of it (approximately 160 works out of a total of more than 300) has sent shockwaves through the Mexican art market. The last news about the collection was that in 2024, Sotheby’s put a lot up for auction. Included were artworks by David Alfaro Siqueiros and María Izquierdo, protected under Mexican cultural heritage law. The government halted the auction.

The law permits their sale, but under the supervision of the INBAL, which typically sets a one- or two-year deadline for the works to return to Mexico. During the announcement of the collection’s relocation, which will be exhibited this June at a new cultural center, the Faro Santander, officials stated that “it doesn’t seem to be in the best interest of the works” and that they are working with the INBAL to explore “a solution that guarantees the best preservation and minimizes stress on the works,” an agreement that “is in the interest of both parties.”

Sources at the bank confirm they are confident they can unblock negotiations, considering the transfer requirement a “pure formality,” reports Rodrigo Naredo from Madrid. When asked for the INBAL’s opinion on the matter, they referred to the statements made by the Secretary of Culture, Claudia Curiel de Icaza, during the announcement of the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, scheduled for the end of the month. “This is the result of months of negotiations with the Gelman Santander Collection,” the Secretary stated.

Given the lack of clear information, market sources assert that “there is great confusion among collectors, who don’t understand if the law is being applied only to some.” These same sources point out that there are already cases where the law is being ignored, such as the Nagoya Museum of Art in Japan, which houses several works by Diego Rivera. Pending further details, historian Luis-Martín Lozano does not lament the departure of the Gelman collection, but criticizes the institutional weakness and lack of favorable conditions in the country for the preservation of this type of collection. “The State is not obligated to purchase these protected collections, but it can create the necessary conditions, with tax incentives for collectors and legal certainty.”

Last week’s announcement also revealed that the new owners, who in turn are transferring the works to Santander, are the Zambrano family, a powerful dynasty of entrepreneurs from Monterrey, the industrial and wealthy north of Mexico. This family owns the cement company Cemex and has a long tradition of art patronage and collecting. As is typical in the secretive art market, the sale price, finalized by the Vergel Foundation, the vehicle Littman founded to operate in the market after Natasha’s death, remains undisclosed. But a Frida Kahlo painting, The Dream (The Bed), sold last November for nearly $55 million. The $200 Littman was asking a couple of decades ago now seems like a pittance.

Former INBAL director Gerardo Estrada considers it a “very strange operation. The Zambrano family, who have the resources and experience for its upkeep, buy it, but then transfer it to Santander. It makes no sense.” The cultural official also recalls that he made one last attempt to get the government to buy it. “About four years ago, I approached López Obrador’s administration, but they told me they weren’t interested and didn’t have the money. Even if they did, it’s been shown that art doesn’t yield electoral gains.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.