An alternative to capitalism is possible, at least in comic books

A wave of recent comics focuses on facilitating the understanding of economics and denouncing labor exploitation and its social, environmental, and mental health consequences

All humans laugh, cry, eat, sleep, and love. Although most of their day is spent on another universal activity: work. As such, complaints about work are widespread, across the globe. Too many hours, stress, demands, sacrifices, and various other things. Since its triumph, neoliberal capitalism has repeated that there are no alternatives. Lately, however, a simple option has emerged to question it. Or to understand the rules and dark sides of the game we all play. Just read one of the many comics about economics, exploitation, and other workplace injustices that are being published right now. It turns out that another world is possible, at least in comic books.

“We have to understand economics for ourselves, or we’re at the mercy of any charlatan,” warns writer Michael Goodwin. He himself has contributed his two cents: first, he delved into decades of treatises and thinkers; then, in Economix (2012), he summarized in comic strips — with illustrations by Dan E. Burr — what he had gleaned: theories, practices, and pitfalls of the last two centuries of development. There, one discovers that even Adam Smith, enshrined in history as a champion of the free market, denounced the “rapacity” of the magnates and urged caution regarding their legislative proposals. Or one reflects on a society that is democratic in its structures but “dictatorial” in many businesses.

“Every public problem or decision is economic. In the U.S., the rich have basically bought the institutions. If we had structured the economy differently, they wouldn’t have been able to. It was our choice. Or it was never presented to us in those terms,” Goodwin notes.

Economix does indeed do this. And it eliminates the excuse of excessive complexity: now understanding — or perhaps outrage — is within everyone’s reach. Like the recent graphic novel adaptation of Capital and Ideology (2024): the original 1,248-page volume can be daunting even for admirers of its author, Thomas Piketty. But Claire Alet and Benjamin Adan’s graphic novel has condensed it to 176 pages. The ideas of the new guru of social justice are presented in simplified, though no less insightful, form. And certainly, more accessible.

Sales have been so strong that another of Piketty’s books, A Brief History of Equality (2021), has just been adapted for the same audience, by Sébastien Vassant and Stephen Desberg. This, incidentally, offers the most paradoxical example of capitalist power: even a critique of the model can become a trend that maximizes profit.

The truth is, there are economic comics of all stripes, tones, authors, origins, eras, and styles. Bienvenido al Mundo (or, Welcome to the World), by the Spaniard Miguel Brieva opts for colorful and explicit satire, where a young girl asks her mother: “Hey, Mom, do poor people really exist?” From the pool and the privileges they swim in, it certainly doesn’t seem so.

Whistle (2022), by Louka Butzbach, instead chooses white, red, and a subtle metaphor: an enormous potato threatening to crush a town.

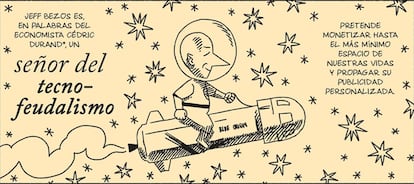

And Darryl Cunningham takes yet another path: previously in Billionaires (2019), and now in Elon Musk: American Oligarch (2025), in which he emphasizes that the climb to the top often involves sacrificing scruples, legality, and workers’ rights along the way.

A conclusion that is shared by How the Rich are Destroying the Earth (2008), by Hervé Kempf and Juan Mendez.

Alison Bechdel offers fewer answers, though many questions, in her book Spent (2025), which tackles another difficulty: capitalism is so all-consuming that even the most principled end up making concessions.

Philippe Squarzoni, however, puts our consciences to the test: readers of La oscura huella digital (or, The Dark Digital Footprint) will not forget the environmental cost of using smartphones or other technologies. “The ice cover over the Arctic in summer has shrunk by more than 40% since 1979,” the graphic essay reports. Every page invites critical thinking, not just self-reflection: “In France, 63 billionaires cause more pollution than half the population.”

Nor will orders be placed so casually after finishing El Maravilloso Mundo de Amazon (or, The Wonderful World of Amazon). Clearly, stepping off the treadmill seems difficult. At the same time, ignoring the consequences of letting it run, after reading these comics, becomes impossible.

Even more so when they prove fatal. Kanikosen, by the Japanese artist Go Fujio (2023), adapts a double death story into manga: the communist writer Takiji Kobaiashi denounced the forced labor on board fishing boats in his country in his 1929 novel of the same name, but it cost him his life, due to police torture in 1933.1

And Cuando el trabajo mata (or, When Work Kills) needs no further explanation than its title and the knowledge that its protagonist’s tragedy is based on real events. “This comic stems from a journalistic investigation into a wave of suicides in companies like Renault and France Telecom. After that, there was some awareness, for a time. The problem has been seen, analyzed, named. But only details were modified, while the issue lies within the system. Fundamentally, nothing has changed,” laments reporter Hubert Prolongeau, co-author along with Arnaud Delalande and Grégory Mardon.

For Goodwin, the current situation is even worse than what is portrayed in the ending of Economix. “We are clearly entering a dystopian era. But it’s worth remembering that it’s more of a failed utopia. Specifically, the one sold to us by free-market economists, which worked in their equations, but not in the real world, and is now collapsing,” the writer points out.

That’s why he created his graphic novel. And he celebrates all the different reactions he has received from the public: those who simply finished his comic and are now better informed; those who kept reading more and more; and even today’s “professional economists,” who got their start thanks to the content of its pages. “Many of us are concerned about these issues, but we don’t know where to begin. And we’re often very busy. That’s why a comic can be ideal,” he adds. Although summarizing it was a lot of work: in hindsight, he realized he wasn’t producing more than a page a day. He would write 20, cut them in half, and then cut more and more. Even then it wasn’t enough in every case: sometimes he threw away what was left and started all over again.

“The advantage is that you reach more people, and it can be simpler. The problem is that it becomes too simple and fails to convey all the complexity. Or, if it tries, it might become difficult and lose its advantages,” Prolongeau observes.

Hence, in When Work Kills, the original research focuses on a single individual. His name is Carlos, but he could be anyone who has seen how quickly hope and ambition can lead to depression and exploitation. Similarly, the graphic novel version of Capital and Ideology follows a family through the decades, allowing the reader to see what descendants sometimes prefer to forget: fortunes and inequalities built on slavery, lobbying, colonialism, and stratagems as illegal as they are unethical.

In response, comics offer some suggestions. Universal basic income is mentioned in both Economix and Capital and Ideology. The anthology Ecotopias compiles several feasible changes, depicting a greener planet and other improvements they would bring. And Prolongeau calls for protecting the mental health of employees: “The paradox of workplace suicide is that it affects the most dedicated people. If you don’t care about your job, you don’t feel that recognition is at stake.”

“There are many options. We don’t even have to imagine them; we just have to look around. Social democracy works much better than unregulated capitalism according to practically any metric,” Goodwin points out. There’s one recommendation that, in a way, sums them all up: slow down, put on the brakes... even stop. Even if it’s just for a while, to read a comic.

Goodwin adds: “It has a minimal barrier to entry, and it can bring more people into these discussions. And not just as readers. It only takes one person to write a comic. Anyone can start today.” As long as they can find the time, because there’s so much to do every day. Laugh, cry, eat, sleep, and love. And work.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.