Royan: Picasso’s refuge in times of war

The artist’s museum in Málaga is showing for the first time eight sketchbooks made during his stay in the French seaside town between 1939 and 1940

Pablo Picasso first came to know Royan, a small seaside resort on the French Atlantic coast, when he was married to his first wife, the Russian dancer Olga Khokhlova. It was the summer of 1923 and, together with their son Paul, the family spent two weeks there before moving to Antibes, on the Côte d’Azur, to enjoy the rest of their holidays. Years later, in the summer of 1939, the Spanish artist and his family had to leave Paris. This time not to rest, but because of the inexorable advance of Nazism and the imminent world war that would end up breaking out on September 1.

Picasso was already a world-renowned artist who still had a Spanish passport and was close to the French Communist Party. His safety was in danger and Royan, some 310 miles from Paris, was the refuge chosen by the artist and his entourage. Between September 1 and 2, 1939, Pablo Picasso and his partner at the time, the artist Dora Maar, arrived at the seaside resort; also with him were his secretary and friend Jaime Sabartés, the latter’s wife, Mercedes Iglesias, and Kazbek, the artist’s Saluki dog. Royan thus became one of the essential cities in Pablo Picasso’s life, along with Paris, Antibes, Cannes, Vallauris, Mougins and the Spanish cities of his childhood and youth: Málaga, A Coruña and Barcelona.

Picasso lived in Royan between September 1939 and August 1940. During that year, his production did not cease, even though circumstances forced him to use other types of materials. He wrote a lot and drew incessantly, as well as executing several oil paintings in which women are the absolute protagonists. He only traveled to Paris on three occasions to check on the security and storage of his works, and to assist with the preparations for an exhibition of his drawings. The Picasso Museum in Málaga now offers an account of what that period was like for the artist with a new exhibition, The Royan Sketchbooks, which can be seen until April 30. The exhibition has been organized in collaboration with the Almine and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso Foundation (FABA), together with the Department of Culture of the regional government of Andalusia.

The walls of the rooms, which have been converted into a large rotunda, reproduce the dark blue of the Atlantic Ocean that Picasso saw from his studio in Royan. The eight sketchbooks, which were brought together in Málaga for the first time (only one of them belongs to the museum’s collection) were school-style notebooks, with square-grid lines and spiral binding, which Picasso used as he sat at cafés or while sitting in the street. The contents of each page can be seen in the projections of the reproductions. Picasso made the most of the paper that he had available. With very small letters he wrote words very close together, mixing Spanish and French, with which he expressed ideas, reflections, poetry, drawings and comments of all kinds.

Transcribing this content is only possible for very experienced Picasso artists, such as the exhibition’s curator, Marilyn McCully, who recalled with emotion at the opening of the exhibition how she felt as she examined the pages: “It’s the closest you can get to the artist, it’s almost as if what was going on in his mind was immediately translated into a sketchbook.” Picasso used sketchbooks throughout his career to jot down visual ideas, with reference to previous works or new ideas for future compositions.

Ramón Melero, the project coordinator, says that at the start of the exhibition there are two very illustrative pieces from Picasso’s Royan period. The first is a palette made from the wood of the back of an ordinary chair. The lack of resources stimulated the artist’s imagination. There is also a striking oil painting: Three Lamb’s Heads (October 1939), loaned by the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid. When he made this oil painting, he had already closed the cycle dedicated to the mural Guernica.

He began a series of still lifes in which he introduced bull and ram skulls, human skulls and many lamb heads that were abundant in his house because they were his dog’s favorite food. The composition of the three gruesome heads is reminiscent of Goya’s Still Life of a Lamb’s Head and Flanks at the Louvre, which Goya painted between 1808 and 1812. It also evokes the pyramid of human skulls painted by Paul Cézanne between 1901 and 1906.

Picasso was concerned about the advance of the German army, and his own personal situation was also a factor. His partner Dora Maar, whose work the exhibition includes in a section with works she made at that time, was living in the same building as Picasso’s former romantic partner, Marie-Thérèse Walter, and Maya, their daughter. They all saw each other on a daily basis, but it does not seem that this family tension had any impact on Picasso’s artistic activity.

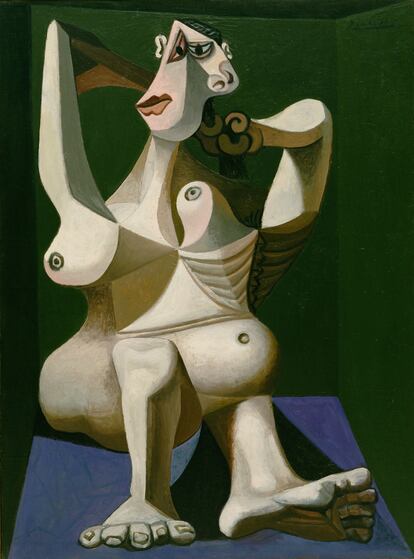

Although the exact number of canvases he painted during his stay in Royan is uncertain, the exhibition includes several works that reflect his creative drive during this period. These include Bust of a Woman with Arms Crossed Behind Her Head (1939), from the Malaga Collection; Woman Dressing Her Hair (1940), from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York; Café in Royan (August 1940) and Woman’s Head (1939). On the back of the painting, Picasso wrote: “For the Greek people, a tribute from Picasso for their resistance to Nazism.” The work was stolen from the National Gallery of Athens and was missing for nine years, until it was found by the police in 2021. The fact that it had the writing on the back of the canvas made it impossible for it to be released onto the black market. The trip to Málaga is the first the artwork has made since its rescue.

When Paris was occupied by German troops on June 14, 1940, Picasso decided to return to the French capital with his entire family. In 1945, the building in Royan where he lived and painted was reduced to rubble in an intense air raid.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.