‘The most vile and grotesque freak show that’s ever been on TV’: How Jerry Springer made history by breaking all boundaries

The Netflix documentary ‘Jerry Springer: Fights, Camera, Action’ examines the program considered the worst in the history of American television. It crossed unimaginable moral red lines but left a legacy that, in part, explains the current political landscape

“If you wanted to save whales, you called Oprah. If you slept with a whale, you called us.” This biting remark from one of the producers of The Jerry Springer Show captures the essence of the most notorious program in American television history. Although it wasn’t a sexual encounter with a whale but rather with a Shetland pony in 1998 that became a turning point for the show.

The program pioneered what came to be known as “trash TV” and even found itself embroiled in a murder case that ended up in court. These shocking events are revisited in the new Netflix documentary Jerry Springer: Fights, Camera, Action — a deep dive into the legacy of a program that TV Guide ranked as the worst show in television history. None of the participants interviewed in the documentary seem to have fully come to terms with their involvement in the Springer phenomenon.

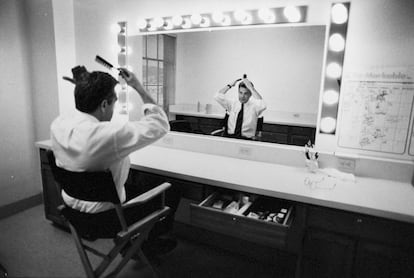

In 1991, American television had one undisputed queen: Oprah Winfrey. Her talk show, filled with tearful confessions and low-stakes drama, commanded an audience of over 12 million viewers. From her perch at the top of the ratings, Oprah looked down on a sea of imitators whose only real distinction was the personality of their hosts. When The Jerry Springer Show debuted, expectations were modest at best. The host, Jerry Springer, was an affable figure with the demeanor of a college professor — the kind of neighbor who’d lend you his lawnmower without hesitation.

A former politician, Springer initially stuck to the formula of the time: sentimental stories of family reunions and personal triumphs. His show blended into the background of daytime television, offering the same fare that filled competing channels. But when NBC executives threatened to cancel the struggling program, Springer and his team made a Faustian bargain that would change television forever.

To breathe life into the failing show, the producers brought in Richard Dominick, a writer responsible for headlines about “Bigfoot’s love slave” and a toaster “possessed by the devil” in the tabloids Weekly World News and The Sun. He brought two transformative ideas that would define the show’s legacy.

The first was to elevate Jerry Springer’s on-screen persona by orchestrating raucous audience chants. Dominick instructed the crowd to leap to their feet and enthusiastically shout the host’s name as he entered. The now-iconic refrain of “Jerry! Jerry! Jerry!” became synonymous with the show.

The second idea was far more consequential: Dominick directed the production team — mostly young, ambitious newcomers eager to leave their mark on 1990s television — to ensure that the stories were “compelling with the sound off.” This mandate led to an explosion of on-set brawls and a surprising number of gratuitous nude scenes.

Springer placed unshakable trust in Dominick’s vision. The only limit was the absence of limits. In the Netflix documentary, Dominick admits, “If I could kill someone on television, I would execute them on television.”

Nothing better encapsulates the paradigm shift in The Jerry Springer Show than the infamous 1998 episode featuring Mark, a farmer from Missouri. Mark appeared on the show to introduce the audience to his partner of 10 years, the individual he had left his wife and children for. To the astonishment of viewers, the “lucky girl” turned out to be Pixel, a Shetland pony.

Mark declared his love for Pixel, detailing their intimate relationship and even plans for a wedding. As he spoke, the show displayed photos of Pixel dressed in women’s lingerie. “When it comes to sex, we make love. We don’t make fun of each other,” Mark said.

The episode aired only on the East Coast. All the networks censored it, and the press quickly took notice. Critics called it “the most vile and grotesque freak show that’s ever been on television.” The result? Everyone wanted to see it — a textbook case of the Streisand effect. Ratings skyrocketed, and for the first time, they beat Oprah.

The producers doubled down. Soon, a trans woman who had sawed off her own legs and two siblings in love discussing their pregnancy appeared on the show. The headlines grew increasingly sensational: “I Slept with 251 Men in 10 Hours!” “I Am a 14-Year-Old Prostitute!” “I Cut Off My Penis!” At NBC headquarters, executives toasted with champagne. Ratings soared, even as critics sharpened their knives. “Showing your soul is one thing; showing your penis is another,” quipped Oprah.

The executives knew that the show was trash, “but the rating were too good to resist,” according to the documentary. While the media blamed Springer for America’s moral collapse, viewers couldn’t look away. “Sometimes people just want to kick back, let their eyes glaze over and learn about a guy who desperately wants to marry his horse. What’s a better form of escapism than that?” Danielle J. Lindemann, author of True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us, told The Times

The increasingly controversial stories escalated to such levels of violence on set that a professional security team had to be hired. Chairs flew, teeth and nails followed, and women flaunted clumps of their rivals’ hair as trophies. More than one guest left the set directly for the hospital. This chaos brought Steve Wilkos, an ex-Marine, onto the show. His presence became so frequent that he eventually landed his own program.

None of the episodes were as violent as the one titled Klanfrontation, which pitted members of the Ku Klux Klan against the Jewish Defense League. The topic was particularly sensitive for Springer, the son of Holocaust survivors, born in London during the Blitz.

A moral man?

Springer was born in 1944 in a London Underground station used as a bomb shelter. His parents, German Jews, had fled to England during the Holocaust and later emigrated to the United States when Jerry was five. A brilliant student, he developed an early passion for politics, working on Robert F. Kennedy’s ill-fated 1968 presidential campaign. After earning a law degree, Springer launched a promising political career that was soon marred by scandal. In 1974, The Cincinnati Enquirer revealed that Springer had frequented brothels and had been clumsy enough to pay with personal checks.

The incident did not end his political career: rather than hide, he openly admitted it. Nor did it harm his relationship with Micki Velton, whom he had recently married. They stayed together for 30 years, keeping their private life out of the media. He also fiercely protected his daughter, Katie, who was blind, partially deaf in one ear, and born without nasal passages — she was her father’s staunchest defender. Springer became mayor of Cincinnati and, before transitioning to national television, was the most beloved presenter on local TV. His charisma allowed him to remain seemingly detached from the sensationalism that surrounded him. Yet, the man hailed on his program as “the hero of the United States” was not as pure as the moralistic homilies he delivered at the end of each show suggested.

The incident with the prostitutes was not an isolated case. One morning, Springer walked into the show’s office and apologized to his staff. They were baffled, but the press soon clarified the situation. A sex tape had surfaced, showing Springer with a stripper and her stepmother — two guests of the show who had conspired to trap and blackmail him. He attempted to suppress the scandal with money, but he couldn’t stop the footage becoming public. Once again, he confronted the fallout head-on. And, once again, he emerged even stronger.

The story that marked the lowest point of The Jerry Springer Show wasn’t necessarily the most scandalous. Nancy Campbell-Panitz appeared on the show hoping to win back her ex-husband Ralph, but upon arriving, she discovered he had married someone else, Ellen, just days earlier. Confronted by her ex, she stormed off the set. A producer chased after her, but she refused to continue with the circus. She knew that the next step would be a fight, rolling on the floor, pulling each other’s hair, and trading insults.

“If you don’t come back, we won’t pay for your return ticket,” they told her. It was a common trick to convince guests, and it worked because many of them came from humble backgrounds. The production team entertained the unsuspecting guests who believed that Springer would truly solve their problems. They provided a lavish experience: a limousine, first-class flights, unlimited access to alcohol, and any substances that would lower their inhibitions. It was a lifestyle the humble guests had never dreamed of.

Nancy didn’t care about the threats. She walked in the rain to the station, where a stranger took pity on her and gave her a ride home. When the show aired a couple of months later, it was just a bad memory, and she didn’t even watch it. Her ex-husband did, however, watching the broadcast in a bar while getting drunk. “I’m going to kill her,” he said as he continued drinking. The next day, her son received a call from the police: his mother had been murdered by her ex-husband. The police issued a warrant for the arrest of Ralph and Ellen Panitz. Ellen was acquitted, but Ralph was sentenced to life in prison. He had a history of domestic violence and prior complaints from Nancy, but no one on the show seemed to care.

Judge Nancy Donnellan, who sentenced Ralph Panitz condemned the role the show had played in the incident. She claimed that The Jerry Springer Show had manipulated them to escalate the humiliation. “To Jerry Springer and his producers, I ask you: are ratings more important than the dignity of human life?” she asked. Since the answer to Judge Donnellan’s question was undoubtedly yes, the show’s machinery continued without hesitation. To distance themselves from the scandal, the entire team traveled to Jamaica to record an episode at a swingers’ resort.

The show took its toll on everyone who worked on it. Dominick subjected them to a tight 20-hour daily schedule. Tobias Yoshimura, a producer since the first show, reached his lowest point when he produced the story of a prostitute who had been abused by her father since she was a teenager. She was going to confront him live, begging him to stop calling for her services and asked not to see him until the taping. They were put up in separate hotels under false names, but when Yoshimura went to visit her to finalize the details of the next day’s show, the father opened the door, covered only in a towel. That same day Yoshimura left the show, unable to deal with it any longer.

Frightened by the growing level of scandal, the network demanded a shift in tone, leading to Dominick’s departure from the show. At the time, competition was fierce, with many networks airing formats that would have been unimaginable a decade earlier — not just testimonial shows, but also reality TV with extreme premises. Trash TV had become embedded in American culture. As television historian David Bianculli put it, the show “was lapped not only by other programs but by real life.” After 27 years as America’s favorite guilty pleasure, The Jerry Springer Show came to an end in 2018. In many ways, the show offers more insight into the current political landscape in the United States than any study by a political scientist.

Jerry Springer, who died of cancer in 2023, never renounced the show that made him a millionaire, although he admitted that he would not watch it. “Television does not and must not create values, it’s merely a picture of all that’s out there — the good, the bad, the ugly,” he told Too Hot for TV. “Believe this: The politicians and companies that seek to control what each of us may watch are a far greater danger to America and our treasured freedom than any of our guests ever were or could be.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.