Rock concerts: The greatest collective celebration of our time

Live music, from Elvis Presley to Coldplay, has intensified the emotions of the public over the last 70 years and accompanied the evolution of the entertainment society

For 70 years, from Elvis Presley to Coldplay, the entertainment industry has been reinventing the rock concert. Music changes with society and technological progress. To understand part of this evolution, specialized music literature editor Julián Viñuales tells me the fundamental book is the choral chronicle Rock Concert: An Oral History as Told by the Artists, Backstage Insiders, and Fans Who Were There (2021) by American author Marc Myers. His account moves forward by stitching together testimony from performers, promoters, sound technicians, spectators... He goes as far as Live Aid, the 1985 benefit concert where one of the legendary performances in the annals of rock history took place: Queen. The stage is set at the start of Bohemian Rhapsody (2018), the Freddy Mercury biopic that culminates in the hyperrealistic recreation of those 20 minutes of perfection at Wembley. But Myers, naturally, starts with the 1950s.

“From that time, we see material resources and cultural attitudes that are still ours. From household appliances, which were then popularized, to rock and roll, which was born then,” wrote Justo Serna and Alejandro Lillo in Young Americans (2014). These young people, perhaps even more so, were the subjects of a sociological change whose expression was rock. Take Kay Wheeler, for example.

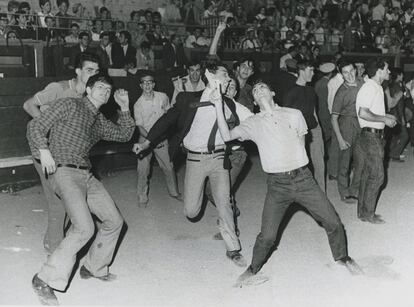

In 1955, when she was 15 years old, she heard him for the first time on the radio, the first rock broadcasting outlet. At the local station, a DJ said that Elvis Presley was ridiculous, so she decided to create a fan club. As it was another opportunity to exploit the Presley brand, Wheeler was invited to a concert on April 15, 1956, at the municipal auditorium in San Antonio (Texas). The singer ushered her into his dressing room, then invited her to watch the concert backstage. It could have been the 3 p.m. or the 8 p.m. show. “As soon as the audience saw him, chaos broke out. There was an instant explosion. There was so much screaming you could barely hear it, an explosion of excitement from the young women.” She was the driving force behind Presley’s first concert in Dallas. It sold 26,500 tickets. Some consider it the first stadium concert.

What was experienced there is what the biopic Elvis relates in its recreation of Elvis’ first concert. If the guitar of folk singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie was killing fascists, Presley’s body, voice and face were stripping away layers of repression. This intensification of emotion from body to brain is probably the most powerful experience you can have at a rock concert. The most common comparison to describe it is the transmission of energy from the musician to the audience. This energy depersonalizes, is fed back by singing and moving the body as a group, and thus the emotion is experienced with an exceptional intensity associated with the spirit of youth.

“What made it exceptional is that Elvis was not singing for our parents but for teenage girls,” Wheeler recalls. It was a moral revolution and it was capitalist entertainment put forward by white men to young girls with purchasing power. Since the advent of YouTube’s infinite archive and the nostalgia industry (commemorative tours, series, biopics, documentaries), “rock is now old enough and established enough as an art form to sustain its own mythological industry,” noted critic Simon Reynolds in his essay Retromania. “The biographies of the authentic rock stars surpass the most imaginative creations, aside from exhibiting the heartbeat of the real,” wrote the maestro Diego Manrique. What was pure present is now also museum-worthy.

The early Beatles of course sang for teenage girls. In November 1963, Beatlemania had already been unleashed, as shown in the documentary Eight Days a Week (2016), which focuses on the years in which they played live gigs. According to BBC radio: “Thousands of teenagers had waited up to 12 hours in Liverpool to buy tickets to see the Beatles. The queue was over a mile long and police had to shut down traffic. Ambulances treated more than 100 people with symptoms of hypothermia. When the tickets ran out, many young women burst into tears.” The hysteria to secure concert tickets is nothing new.

The documentary contains a clarifying scene. It is February 1964, the Beatles’ first trip to the United States. Two days earlier, they had debuted on the mecca of entertainment: The Ed Sullivan Show, which would receive 50,000 requests for a studio with a capacity of 728 people. They were on their way to Washington. On the train, a journalist interviews Paul McCartney.

— What place will The Beatles occupy in the history of Western culture?

— You’re kidding, right? This isn’t culture. It’s having a good time.

The first U.S. concert was in Washington. As usual, it lasted around 30 minutes, like one of the concerts that also holds a place as one of the most important in history, at Shea Stadium in 1965. Twelve songs. The sound was fed through the public address system used for baseball games and spectators were not allowed near the stage. There was screaming and hysteria in the bleachers.

Between their Barcelona and Madrid shows and that legendary one in New York, one concert changed the history of rock. Bob Dylan at the Newport Festival and his committed folk audience feeling betrayed by the transition of their icon to the commercial electricity of rock n’ roll. It is the subject of Martin Scorsese’s memorable documentary No Direction Home (2005). Musician and sociologist Hans Laguna, author of Hey! Julio Iglesias and the Conquest of America, explains that it was precisely this transition that allowed rock to be reconsidered. It ceased to be entertainment and was legitimized as culture.

But it proved impossible to transfer this evolution to live performances. In July 1966, the Beatles played their last concert; in May, Dylan went into hibernation. His tour, which had showcased the metamorphosis with its acoustic and electric parts, had taken the singer out of sync with his fans. For 20 years, his performance at London’s Royal Albert Hall was the most famous bootleg album.

This evolution of rock would change the emotions that intensified at concerts. As the artists succeeded each other on an open-air stage, drugs helped to push the boundaries of consciousness. In the summer of love in 1967, the first great cycle of festivals began. We can relive them with a certain quality: professional filmmakers, such as the verist D. A. Pennebaker, recorded them with mobile cameras to create rockumentaries on the big screen.

The list is well-known: Monterey, with the audience enchanted by Ravi Shankar’s sitar, Hendrix’s guitar, and the radicalism of The Who, who ended the set by smashing their instruments. Somehow, also, the Rolling Stones in Hyde Park in front of 250,000 people, or Woodstock, which was immediately mythologized as a generational milestone: utopia was possible. Days later, Joni Mitchell modeled the vital impact with her song Woodstock: I’m going on down to Yasgur’s Farm / I’m gonna join in a rock and roll band / I’m gonna camp out on the land / I’m gonna try and get my soul free. That experience of the atavistic myth was a mirage.

At the end of 1969, at the Almont Festival, there was a homicide and three accidental deaths. This lack of control is relived in the documentary Gimme Shelter. And, although without violence, chaos emerged again in the summer of 1970 at the Isle of Wight Festival. Concerts by The Doors, Leonard Cohen or The Who were released on disc much later. But perhaps the most significant is the Joni Mitchell concert recovered in the documentary Both Sides Now (2018): that angelic woman, with lyrical songs of unfathomable beauty, was booed and the stage assaulted by a guy in full lysergic trip.

The concert crisis was resolved with a new mutation, according to Myers. We’re not talking about the club circuit. Here the industry is key. Record store chains were expanding, more and more live albums were being released — few as mythical as Deep Purple’s Made in Japan, to which Carlos Fernández dedicated a monograph — and touring was a way to promote a new album, the main source of income for bands. At the same time, the concert business became more professional. Sound and staging improved. Awareness of spectacle was regained, with rites that are repeated and that the spectator knows in order to experience a mystique: the new emotion was already intensity.

Most of the tours that Rolling Stone — the magazine that canonized rock — selected to feature on a list of the best concerts in history are from that era. A paradigm could be David Bowie reconverted into Ziggy Stardust or the KISS circus. “They blew it up with a powerful combination,” explains Dave Grohl of Nirvana in the series The Story of KISS (2021). “Lights, explosions everywhere, fire... nobody has done it that big.” Rock lost cultural consideration, Laguna argues, and went back to being entertainment.

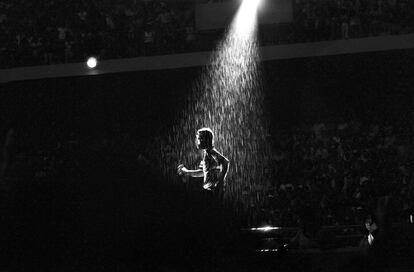

From that dynamic, Spain during the Transition was still on the sidelines. Although a precarious live music industry was created, the big bands did not play here. Promoter Gay Mercader began to correct this anomaly by organizing the first big international rock shows in the country following the end of the dictatorship. In 1981, Bruce Springsteen played in Barcelona, a performance that is the subject of a recently published photography book by Francesc Fàbregas. “It was the greatest concert I have ever attended”, Springsteen’s manager wrote. “It wasn’t freedom; it was liberation.” The other classic was the Stones’ 1982 double bill at the Vicente Calderón.

Rosa Montero’s chronicle of that concert marked by a universal deluge is honey. “Right in the middle of the chaos and commotion, they come out, the Rolling Stones, as if in a Jupiterian din. It is confusion, ecstasy.” From that ecstasy, Montero, with a perfect stylistic break, resituates the reader in normal life after the concert. “Afterwards, all that remains is routine.”

This is the paradigm in which we grew up. It persists in some cases, but, according to Jordi Herreruela, director of the Cruïlla Festival, it is no longer the dominant one. With the advent of streaming music platforms, the business has changed completely. Out of every €10 generated by recorded music, the artist earns €1; out of every €10 from live music, €7. The tour no longer serves to promote a new album; an album is the pretext to start a new tour. This economic dimension is explained by Nando Cruz in the fundamental Macrofestivals. The black hole of music. Concerts have become even more professionalized and adapted to be recorded and made viral by spectators.

“Live shows are much more visual,” says Herreruela. He cites the examples of Coldplay’s bracelets or the elements that appear and disappear in the global phenomenon that is Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour. “Rosalía’s super productions with cameras explore new formats: since we have the technology, for example vertical screens, she uses them to make the live performance a cinematographic experience,” explains Aïda Camprubí, cultural critic and co-director of the BAM Festival.

What does the future hold for the rock concert experience? Herreruela’s thesis is that concerts are held in sports venues that were not designed for these types of show, but the Sphere in Las Vegas is the first example of a venue created precisely for this purpose. In September 2023 it was inaugurated by U2, the resident band for 40 nights. A similar venue is being built in Manchester. If you have facilities of that kind, the stars will come. “Currently, concerts are an activity that get more people out of the house than soccer,” says Herreruela. “It’s the collective celebration that has the most impact.” No one wants to miss out on experiencing the ecstasy.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.