Steve Van Zandt, the nice guy who stood up to apartheid

The HBO documentary ‘Disciple’ profiles an artist who is much more than Bruce Springsteen’s guitarist and the actor immortalized in ‘The Sopranos.’ In the 1980s, he mobilized the music industry to cut ties with South Africa’s racist regime

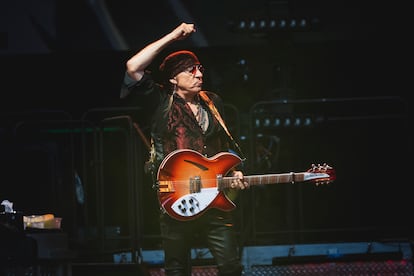

Some guys have all the luck. Steve Van Zandt wanted to be a rock star and has been living that dream for nearly a half century. Some see him as merely Bruce Springsteen’s guitarist in the E Street Band, but it would be a mistake to assign Van Zandt supporting character status. He’s the total musical package: he composes, arranges, produces and sings. The Boss’s career bears his fingerprints; Van Zandt has even had a notable solo career. And one day, lacking any prior experience whatsoever, he decided to try his hand at acting.

He wound up playing a memorable role on The Sopranos, one of the most important series in the history of television. His long-lasting marriage with actress Maureen Van Zandt was memorably officiated in 1982 by Little Richard, a rock legend turned preacher. Maureen played mafioso Steve’s wife on The Sopranos. Though the couple have been together for more than 40 years, the guitarist’s relationship with Springsteen has been going for even longer — since 1974, though they’ve taken long, if amicable breaks during that time.

Steve has assumed the lead role on other projects: Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes, the other great 1970s New Jersey band, and is the frontman of Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul, a role he’s played since the ‘80s. He’s also a respected radio DJ, a musical entrepreneur. And of course, Springsteen continues to tour with him and the rest of the E Street Band, selling out stadiums and delivering concerts that last over three hours, in which everyone involved gives their all.

The 73-year-old musician, who is also known as “Miami Steve,” a tagline Bruce gave him, and as “Little Steven,” a homage to Little Richard, is the protagonist of Steve Van Zandt: Disciple, which was produced by HBO and is now playing on Max. It’s an authorized documentary, clearly, in which appear the man himself and his entourage: Maureen, his accomplice Springsteen and other collaborators and musicians who see Van Zandt as a major influence. Even Paul McCartney, Van Zandt’s childhood idol, whose musical chops led the guitarist to dedicate his life to rock after seeing The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Although, Van Zandt says his rock ‘n’ roll carries with it heavy soul influences.

Directed by journalist and documentarist Bill Teck, the feature film portrays a nice guy from New Jersey, the clown who entertained everybody during get-togethers, and a tremendous musician, restless and hyperactive. He comes from an Italian family, speaks the language fluently. His last name was Malafronte until he took his mother’s family name, which is of Dutch origin. In the early days of his career, he dressed in a suit with a vest and hat; but his later look is better-known, that of the colorful, pirate-esque headscarves.

When he started playing with Bruce, he continued to produce Southside Johnny and would often escape to a payphone cabin to deliver instructions to that parallel project. The musicians became household names. Just as Bruce was at the height of his fame (after the release of 1984′s Born in the U.S.A.), Van Zandt began a solo career that achieved only mild commercial success, but did manage to make a certain impact in Europe. On one of his tours through Italy and Germany, Van Zandt realized that he was seen as a symbol of his country, the United States. His response? “I never thought of myself as an American — I’m from New Jersey!”

It was around this time that he had a political awakening that would take centerstage throughout his next chapter. He began to make message-based music that criticized U.S. interventionism. He became interested in Nicaragua, in the mass disappearances taking place in South American countries, and supported Indigenous rights in North America. In the mid-’80s, during a tense moment in the Cold War in which the United States installed missiles in Europe, he told a German audience, “I have to apologize for the arrogance of my government and the ignorance of my compatriots.”

His life’s great cause, of which he is proud, was the fight against South African apartheid. He visited the country and went to Soweto to meet with the Black population, who was being brutally marginalized. But he realized that his trip was not well-received. Some residents even met him with their machetes brandished: he was a Western, and he had crossed the military’s blockade of the area. They saw him as they did other musicians (Queen, Elton John and Rod Stewart) who had broken the boycott by performing in the whites-only complex Sun City, which was located on the lands of the Bantustan Bophuthatswana that had been stolen from their rightful owners. On his return to the United States in 1985, he launched a key project in the politicization of the era’s rock, which he called Sun City. For the album, he recruited stars from across several genres: Lou Reed, Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Peter Gabriel, Rubén Blades, Bono, Jimmy Cliff, Bonnie Raitt, Joey Ramone, Ringo Starr, Pat Benatar and of course, Springsteen. They called themselves “Artists Against Apartheid.”

Has the impact of Sun City been subject to exaggeration? It was not the only anti-apartheid campaign, but it certainly resonated strongly and broke boundaries. It got airtime on MTV, which up until that point had avoided involvement in polemic issues. And it took place during a great moment in rock ‘n’ roll for social causes, coinciding with the era of festivals like Live Aid (1985), which took up the cause of hunger in Africa, and that which celebrated the 70th birthday of Nelson Mandela in Wembley Stadium (1988). Van Zandt says that the artist mobilization influenced U.S. Congress to override President Ronald Reagan’s veto on sanctions against the racist South African regime. When Mandela got out of prison, on his first visit to the United States, he appeared in a press conference alongside Van Zandt.

Everything turned out alright for the guitarist, eventually, but in the documentary, he does talk about a low point in his career. The growing activism evident in his lyrics began to close doors for him at record labels and radio stations. He saw no way out of this commercial malaise, and for seven years during the ‘90s, he retired from performing to devote himself to walking his dog, he says. But completely out of the game he was not, starting to work in the audiovisual industry, where he composed and worked on soundtracks. Around the turn of the century, everything changed for Van Zandt once again: HBO offered him a role that had been inspired by him on The Sopranos and Springsteen got the E Street Band back together. Another busy period followed, recording episodes and albums on the same day, interspersed with interminable tours. Those close to him say that he merged with his role as Tony Soprano’s consigliere during this time, that it was hard for him to avoid using his character’s gestures and expressions. There have been more roles thought up for him, most recently in the Netflix series Lilyhammer. At the same time, he is going back to performing with his group Disciples of Soul and has fulfilled a childhood dream: playing with McCartney at the Liverpool venue The Cavern.

But the fast life hasn’t made the nice guy unhappy. He finds time for everything. Another one of his missions has been to shed light on the rock ‘n’ roll legacy and the memory of the artists and songs that have been forgotten, and to bring awareness to new talent. He’s been doing this work for 20 years on his radio show and podcast Underground Garage, which is broadcasted on 200 channels around the world. He has gotten involved with a project to raise awareness of rock ‘n’ roll history in schools, organized festivals and competitions for emerging bands, and even created his own record label. He was a major booster for the comeback of The Rascals, a New Jersey band he listened to as a kid. “Rock ‘n’ roll is spiritual nourishment in a world gone mad,” he says.

It’s all laid out very positively in the documentary. No one says a word against anyone else. A certain doubt remains as to whether Van Zandt has some dark secret he’s hiding from us, or if it’s true that everything can work out nicely for a nice guy from New Jersey.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.