‘Caprichos,’ ‘Disasters,’ ‘Disparates’ and ‘Tauromaquia’: All of Goya’s prints, together for the first time in one exhibition

The San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid will display more than 200 works that the Spanish genius left in four famous series: ‘Not even he ever saw them all together in his lifetime’

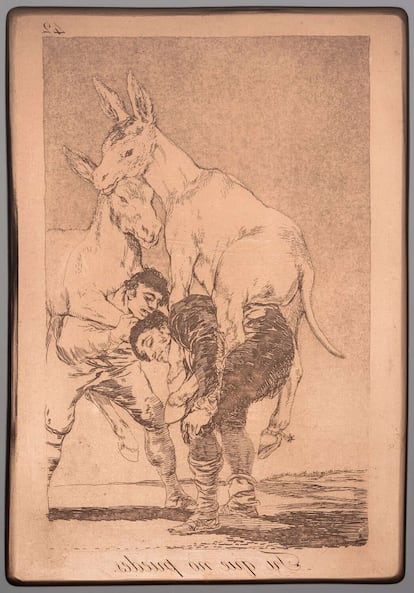

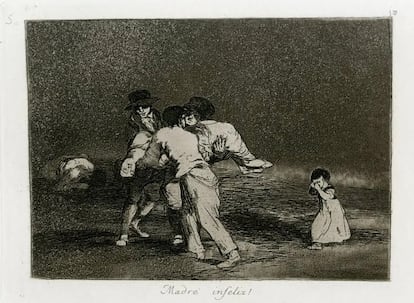

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) had been painting for the Bourbons and the enlightened aristocrats of Madrid for more than two decades when he began to focus on his most personal, risky and ambitious work of the time: his prints. Without commissions, requests or any guarantee that he could sell them, the genius of the Spanish Enlightenment confined himself to portraying Spanish society (its dramas, its daily life, its fun, its ignorance, its needs, the vices of the clergy and the devotion to witchcraft) through a series of prints. During his lifetime the endeavor failed miserably, as Goya was unable to find a way to reach a larger audience, but today these prints are considered a sublime expression of the reality of the moment, a reality that he knew how to turn into art. Nobody had dared to do it before.

The San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid — the same one that rejected Goya at the beginning but which today houses one of the most important collections of his art and the only lesson he left in writing — will on Friday open an exhibition that is unique: for the first time in history, the more than 200 plates made by the painter will be shown together, along with the prints that he made from them. All of his print series are there for the first time: Los caprichos, Disasters of war, Los disparates and La tauromaquia. Most of the plates have also been restored thanks to a new technique discovered in Rome.

The exhibition is called El despertar de la conciencia (The Awakening of Consciousness) because, as its curator, the academic Víctor Nieto, explains, this was the moment when Goya “departed from academic conditioning and changed his attitude as a painter, an activity he no longer saw just as a profession but as a means of expressing his own vital and critical attitude.”

Fellow academics Estrella de Diego and Javier Blas enthusiastically showed this newspaper the preparations for the exhibition on the eve of the opening. They also explained something that is causing enormous pride in the Academy: the team in charge of the restoration has managed to remove the steel that covered the original copper on which Goya worked directly, and has recovered the plates as they were originally. The restoration was carried out by a team made up of specialists from the Academy, from Carlos III University, from the Prado Museum and from the National Institute for Graphic Design of Rome who had previously managed the same feat on plates by the great Italian engraver Giovanni Piranesi. “Goya’s hand is right here. Here you can see how he engraved with etching, aquatint and then the direct touches with a burin,” said Javier Blas, showing one of the prints from the Tauromaquia series and adding something important: the last picture in this series is a dead human being, and not a bull.

In fact, despite the widely held view that Goya’s Tauromaquia series reflects unmitigated applause for bullfighting, it must be noted that his depictions of it included the least festive and the most cruel side of a tradition that already back in his time had undergone some prohibition and questioning. Goya always introduced critical reflection in his work, without coming down fully on one side. This is what he did with bullfighting, for example, but also with the monarchs that he portrayed, the royal families, the Catholic Church, women and the common people. There was never servility in his gaze, no blank check, but rather an independence of will and a truth that are magnified in these freely created prints that serve as a prelude to a darkness that would find its climax in the Black Paintings.

The Spanish genius always said that he had three teachers: Velázquez, Rembrandt and nature. And it was the engravings made by these two painters that he studied until his eyesight gave out. He learned from Velázquez by copying his works. This initial body of work will also be exhibited later at the Madrid venue.

But the highlight is the 213 plates and their prints that make up Goya’s four major print series and of which only a small part had been on display until now. The venerable Academy — which was founded in 1752, just a few years after Goya’s birth — has finally pulled out all the stops and is displaying the 80 Caprichos, the 82 Disasters of War, the 33 pieces of Tauromaquia and the 18 Disparates (except four that are still in France). Later, the 18 Disparates will rotate with the 13 Etchings of paintings by Velázquez, in addition to The Garroted Man and San Francisco de Paula, which will allow audiences to view the complete treasure: the 228 plates and their prints.

“It is the first time in history that they are going to be exhibited together. No human being, not even Goya himself, ever saw them together like this,” said Blas, detailing the difficult journey that Goya experienced with this portrayal of real society: of the Caprichos, produced at the end of the 18th century, he only printed and sold a few copies, and ended up delivering the plates to the Royal House to avoid a trial by the Inquisition. He made the plates for the Disasters of the War of Independence, but did not print them, because they were too dangerous; Tauromaquia did get printed, but it also sold very little. And the Disparates series, enigmatic and unfinished, he kept to himself. “If the Disasters were difficult to sell, the Disparates were difficult to understand,” said Blas.

Estrella de Diego, who is also a writer and art teacher, explained the difficulty that the prints had in Goya’s time: “Goya depicted death, old age, the grotesque, and that made the public uncomfortable,” she said. Not in vain do these series collect the darkest and most critical themes that the artistic genius would later capture on the walls of his Quinta del Sordo, his last resting place in Madrid, where he would express the anguish and despair of a Spain that became unhinged after the return of King Ferdinand VII: the Black Paintings.

The plates and their prints will hang alongside memorable paintings temporarily loaned by the Prado Museum and other works relocated by the Academy itself. These include the portraits of writers Leandro Fernández de Moratín and Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, extremely innovative and brave paintings such as The Madhouse or The Burial of the Sardine, as well as some self-portraits. But it is the prints, Goya’s most intimate work, that have gone down in history in a special way by also collecting his wisdom-laden philosophy in phrases such as “The dream of reason produces monsters” or “I’m still learning.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.