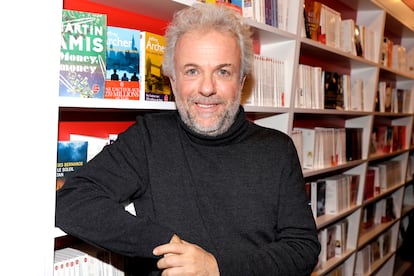

Philosopher Frédéric Lenoir: ‘Porn creates fear of sexual relations’

The French author just published ‘Desire, A Philosophy,’ a book in which he offers a historical and philosophical journey to understanding the nature of our desires and how to direct them toward what really benefits us

Our conversation with French philosopher Frédéric Lenoir flows best on level ground. It’s not that this author, who has sold millions of copies of his books, avoids controversial topics or is averse to confrontation; he’s simply connected to the video call from a car, accompanied by some friends, and the connection worsens markedly as they drive up the side of a mountain on a Los Angeles highway. “You just caught me in the middle of a road trip, and my friends have a nonnegotiable commitment. I promise that we’ll pull over to the shoulder as soon as we can,” he apologizes.

They didn’t reach the shoulder until the last question. Luckily, Lenoir’s explanatory clarity in his work withstood a conversation that froze with each change of altitude. The author just published Desire, a Philosophy in which he addresses the importance of desire in human life, the need to regulate it in a world saturated with options and technology, and the role of social media, consumer society and pornography in the decline of what philosopher Henri Bergson called élan vital (vital impulse in French).

Question: In your latest book, you state that “a human being without any desire is one of the living dead.” Why is desire so important in our lives?

Answer: As Spinoza said, I believe that desire is what constitutes our uniqueness as human beings. It is the fundamental driver of our existence; without it, we would not feel like living or getting up in the morning. To some extent, depression is an illness that can be defined as the absence of desire. I am firmly opposed to the ascetic approach that seeks to suppress [desire], because I believe that would be tantamount to losing our humanity. For me, the key is how to direct the impulse of desire constructively.

Q: You even connect desire to the environmental crisis. Does the future of humanity reside in learning to regulate our desires?

A: Yes. The current alliance between technology and environmental liberalism allows most of us to respond to incentives from the most primitive part of our brain, which makes us always want more. This is catastrophic from an ecological point of view because infinite growth is impossible in a finite world with limited resources. It is also a source of permanent dissatisfaction for those who are never satisfied with what they have.

Q: How is it possible to distinguish authentic and beneficial desires from the ones inculcated by consumer society, the family or dominant religions?

A: We cannot escape from what Socrates tells us: know thyself. We must be introspective and observe ourselves. This is a work of critical observation of oneself, which can be carried out through psychoanalysis, personal introspection, or meditation. With time and experience, one gets to know oneself. This is what Jung calls the individuation process. Normally, it occurs between the ages of 35 and 50, since before that, one is trapped in the influence of society and family. However, there comes a time, in midlife, when one asks oneself: Have I chosen my profession well? Have I chosen my partner well? Maybe I need to do something that will make me feel happier and more useful in society. That is why many people seek therapy and reorient their lives at that age, because we look for what is right for us as individuals.

We should all limit our desires in order to be happier and improve our quality of life.”

Q: You practice fasting and only allow yourself 20 minutes of news each day; you are also an outspoken advocate of mindfulness. Don’t these practices contribute to “suppressing desire,” as you have previously asserted?

A: I am a true epicurean. Being epicurean does not mean seeking an abundance or quantity of desires, but rather prioritizing quality over quantity. It is better to have a little food of high quality than a lot of food of low quality. This ethic focuses on moderating our desires, not suppressing them altogether: it is about limiting them to what is essential and valuable. By fasting, I seek to train my body to limit its cravings and savor food even more. By restricting the amount of news I consume on a daily basis, I seek to avoid the mental saturation and stress caused by an excess of information, which is usually negative. I would say that we should all limit our desires in order to be happier and improve our quality of life.

Q: Was it easier to manage desire in Epicurus’s and Aristotle’s time than it is today?

A: Yes and no. On the one hand, the management of desire has been a subject studied throughout the history of philosophy. In that sense, the core of the human being has not changed. The social environment has changed drastically, exacerbating the difficulties in regulating desire, because today we cannot [help] but desire. The possibility of doing everything complicates the lives of many Westerners, who are often undecided, they don’t know what they want or what is best for them. A modern disease, which Alain Ehrenberg’s The Weariness of the Self describes well, is the exhaustion that results from trying to be authentic. The quest for authenticity is fine, but it can be exhausting, and many individuals feel tired because they have too many options from which to choose. When you have so many options, you try to do everything and, ultimately, you don’t do anything well. Again, we find ourselves focused more on quantity than quality.

Q: In the book, you analyze how young people’s desires are manipulated, especially through social media.

A: The vast majority of teenagers are completely hooked on social media. It’s a kind of slavery; they constantly need to check [their] notifications. In fact, workers at major technology companies acknowledge that social media is designed to manipulate the young people’s minds, feeding their need for recognition through “likes.” The dilemma is how to regulate that, which is very difficult because it is extremely hard to regulate social media globally. Personally, I believe more in self-discipline. On the one hand, parents should limit their children’s use of social media as much as possible; [on the other hand], the best we can do is to offer teenagers something that motivates them more than social media.

Q: Like what?

A: The philosopher Baruch Spinoza explains that it is possible to overcome an addiction to a misdirected desire that makes us unhappy simply through the power of reason and will. To achieve that, it is necessary to create positive affection [that is] more powerful than [what] we wish to counteract, thereby redirecting our desire toward something—whether it is a person, an activity or an object—that will bring us greater well-being. I know of a young girl who was completely addicted to social media. Her parents tried to help her overcome this addiction and discovered that she was passionate about horses. Now, horses have become her new passion, and she has beaten her old addiction. It is crucial to offer them real experiences that give them more satisfaction than what they can get on social media.

Q: You also express concern about sexual burnout among young people.

A: Indeed, there is a problem of sexual desire in the younger generation. Several studies have shown that young people have less and less sex drive, which is primarily attributed to the consumption of pornography. Sex scares them. Kids are concerned about the idea of performance associated with sexual activity. Many young adults talk about their fear of not being good enough, of not providing enough pleasure for their partner, or not receiving enough pleasure themselves. Girls are concerned about not enjoying themselves as much as they expected [they would] and are more afraid of violence. For that reason, they prefer to opt for chastity rather than facing the risk of forced sex or sexual practices. Porn creates fear, no doubt.

People have become accustomed to the virtual world, so direct interactions are more confusing and complicated.”

Q: And physical contact, too.

A: People have become accustomed to the virtual world, so direct interactions are more confusing and complicated. Young people are no longer sure what they want, they are afraid to establish relationships, and they are afraid of the other person. They decide that they can be better satisfied individually than in the company of another person. All of these factors now make direct physical relationships—and not only those of a sexual nature, but also emotional and affective relationships—intimidating for many people.

Q: Some young people, especially boys, have found refuge in Stoic doctrine.

A: In my opinion, Stoicism’s success today is due to several factors. The first is its accessibility. There are a number of maxims, prescriptions and formulas that one can try to apply in one’s daily life. The Stoics understood this dimension of practical philosophy, which can help us live well through principles that are perfectly applicable today. For example, in his Manual for Living, Epictetus differentiates between what is within our control and what is not; what depends on us is what we can change, while it is better to calmly accept what is not [within our control] instead of getting frustrated, so we can avoid suffering twice. These teachings are the key to a fuller life.

Q: And what’s the other reason?

A: The other reason is that it teaches us to regulate our desires. It teaches us to let go... In a world where we constantly desire things, where we long for everything but cannot have everything, we feel deeply dissatisfied and trapped in a frenzy of desires. As Kant rightly said, seeking happiness through desire is an irrational fantasy. Stoicism teaches us that, in order to be happy, we must limit our desires and accept reality as it is. [We have] to learn to say yes to life, let go of ballast and accept reality. That work of accepting reality is a good philosophy, and it is at the heart of Stoicism.

Q: Three years ago, you publicly condemned the creation of the public health pass and the decision to confine people to their homes during Covid-19.

A: I am convinced that one of the best ways to live fully and truly feel alive is to accept death. If our whole life is organized around the fear of dying, we run the risk of leading a very limited and small life. The Covid-19 pandemic years have underscored this obsession with health in many people and in the political management of the crisis: nothing mattered more than saving as many lives as possible, even at the expense of individual freedom and everyone’s psychological and emotional balance. In the spring of 2020, I condemned the policy of elevating health as the supreme value. The fear of death leads us to make individual and collective decisions that limit life, sterilize it and take away all its flavor.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.