The return of Billy Joel: What’s a multimillionaire rock star doing, putting out a song 17 years after his last release?

TikTok’s algorithm and teen idols like Olivia Rodrigo are bringing back the legendary rocker, who is reappearing with a new single, 31 years after his last album, motivated by the love of music alone

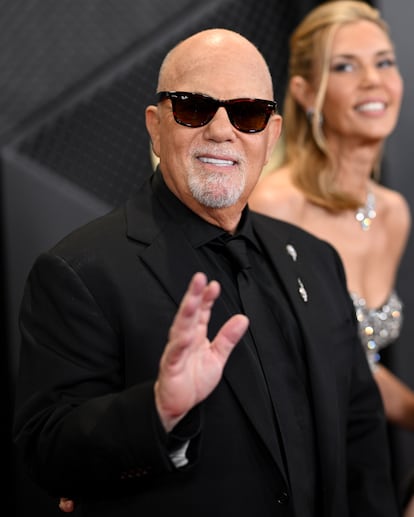

Billy Joel attended last Sunday’s Grammy ceremony like brides attend Anglo-Saxon weddings: with something old, something new, and something borrowed. The “new” was Turn the Lights Back On, the first song he has released in 17 years. The “old,” You May Be Right, the hit track from his 1980 album Glass Houses. And the “borrowed”? Had to be the energy, momentum and rock star attitude bequeathed to him, it would seem, by one of his most illustrious next-generation fans, 20-year-old Californian singer Olivia Rodrigo, who insisted on singing a duet with him a year and a half ago, which she calls the fulfillment of a childhood dream.

Turn the Lights Back On is a ballad about the passage of time and life as an act of resistance. It sounded, appropriately solemn and somber with Joel at the piano, backed up by an orchestra. In contrast, in his reunion with You May Be Right, the singer pulled out all the stops and accelerated through the curves to deliver a swift version with unprecedented forcefulness.

Between one song and the other, an interview fragment was shown in which the 74-year-old New Yorker explained why he stopped composing in 2007 and has not released a pop album with new material since 1993: “A lot of people have asked me, ‘Why’d you stop writing?’ Because I didn’t want to. Some people, maybe they have a great time with it. I kind of suffer with songwriting.”

He closed the tap from which songs flowed, but he never stopped performing. As musicologist Ryan Raúl Bañagale explains, the Bronx singer-songwriter “Joel released a new album every 12 to 16 months” between 1971 and 1993, until he had put out “more than 120″ songs that have made him the fourth most successful U.S. musician in history, a very short distance behind Michael Jackson. His refusal to continue adding to his songbook (though he did release 2001′s Fantasies & Delusions, a classical music album in collaboration with Korean-born pianist Hyung-ki Joo) has rendered him a “timeless” performer, oblivious to trends, with a laser-focused live schedule that, at times, has had him performing in a hundred concerts a year. He has filled stadiums, starred in massive tours alongside his (supposed) rival who is, in reality, an old friend and accomplice, Elton John. In a sense, he has been more active than ever during the last 30 years. But he is no longer building an empire, but rather, managing a legacy.

What the fans want

Joel himself has explained this trajectory in a sensible, elegant manner. His true contributions to the canon are songs like Honesty, Just the Way You Are and Uptown Girl, which were all written more than 40 years ago. People can’t get enough of them, and he doesn’t feel capable of “producing new songs that live up to” his old repertoire: “Billy Joel fans come to see me sing Uptown Girl.” What would be the point of trying, at this point, to sell them on a different product than the one they really want to buy from him?

At the end of the day, not all artists can be asked to display the restlessness and disruptive coherence of a Bob Dylan or a David Bowie, two elusive creatives who have been forever disposed to resist the expectations of their fans. In a similar vein, it’s not easy to follow in the steps of a magician like Neil Young, who continues to pull rabbits out of his hat like Human Race and Don’t Forget Love, but who still features 50-year-old classics like Heart of Gold in his live performances.

Joel has taken pains to explain that his new single is just an exception to his rule, the result of the insistence of producer and composer Freddy Wexler. A fan of the Piano Man since his youth, Wexler managed to get in touch with his idol thanks to his wife’s public relations skills. Joel met him after one of his concerts at Madison Square Garden, where he has been the resident artist for the last 10 years. (He’ll say goodbye to the venue in July, when he hits the 150-performance milestone.)

The two men hit it off. Wexler proposed that they write a song together and, after nearly two years of badgering, got him back into the studio to record a song on which another pair of songwriters, Wayne Hector and Arthur Bacon, also collaborated.

It was supposed to be a private recording, a simple experiment that Joel was prepared to unceremoniously bury if he found the results unconvincing. “I listened back and I didn’t hate my voice, which I usually do.” Joel says that Wexler’s enthusiasm was contagious. “The whole point of doing what I do was because it was so much fun to do when I first started. I kind of lost that after a while. Freddy got me to find the joy in it again.”

A belated (and reluctant) resurrection

The song was released on February 1, three days before Joel performed it live for the first time, as a nostalgic finale to the Grammy ceremony. For Bañagale, it has “all the markers of a classic Joel ballad,” starting with “the rhythm and rolling chords of She’s Always a Woman,” the exhortation to accept others without reservations or reticence as in Just the Way You Are, and even “a lick in the piano solo some may recall from Scenes from an Italian Restaurant.” In short, a track that may not add anything truly substantial to Joel’s catalog, but that does represent a more than worthy way to bring to a close a period in Joel was what Bañagale describes as “creatively dormant.”

His has been one of the longest creative silences in the history of popular music, with the exception of the 37 years and 10 months that separated Chuck Berry’s penultimate album (Rockit) from his latest (Chuck). Berry’s nearly four-decade hiatus can be attributed to his unhinged and frenetic lifestyle, which featured various convictions for tax evasion, brawls, sexual abuse and drug possession between 1979 and 2017. His only reason for returning to the recording fold after such a long absence was that he had just turned 90 and felt the time had come to bid farewell to the world by leaving what would turn out to be a posthumously released album, dedicated to his wife and life partner, Themetta “Toddy” Suggs.

Joel’s has been a much less eventful journey. In August 1993, he released River of Dreams, his 12th studio album. It went quintuple platinum in the United States, the equivalent of more than five million units sold, and was a notable success in places like Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Germany and the United Kingdom. But its author, as he declared to Vulture in 2017, felt he was the object of an incomprehensible boycott by TV stations and his own label (Columbia) that made him lose his last bit of faith in the record business.

Moreover, Joel clearly believed that he was becoming an out-of-date artist in his stubbornness to produce weighty music. “I grew up in the era where an album had to be substantial,” he said, in contrast with a new industry-wide context in which only image and marketing push the needle. At 44 years old, he felt like an old couch. He was so tired of the paternalistic disregard with which, in his opinion, he was treated by a large part of music critics, who were prone to categorize him as a guilty pleasure, a symbol of bad taste and of the cultural indigence of the profane, the artist that so many loved to hate.

So, he decided to retire to his comfort zone: the hundreds of thousands of fans that had been accompanying him since the beginning of his career. They weren’t perhaps enough to raise him to the multimillion sales of Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, Garth Brooks, Sheryl Crow or Bryan Adams, but they were more than enough to ensure the viability of his tours and concerts. River of Dreams, by the way, concludes with a phrase that would turn out to be, to some extent, prophetic. The line comes near the close of the song Famous Last Words: “These are the last words I have to say.”

A (generational) bridge over troubled waters

One wonders how a septuagenarian who had embarked for a decades-long nostalgia operation managed to win the adoration of a Gen Z luminary like Rodrigo. In her track deja vu, released on her debut album Sour, the Murrieta, California-born singer quoted Joel. She did so at the suggestion of producer David Nigro, after he noticed that the song was vaguely reminiscent of Uptown Girl. Once the album was released, Joel and Rodrigo exchanged platitudes. He lauded the freshness and authenticity he perceived in the work of the teenager, a newcomer to the business. Rodrigo declared herself a fan of the veteran who, in her opinion, was still in top form, relevant as ever. Their mutual regard led to their celebrated duet at the Garden in New York in August 2022, during which they performed both deja vu and Uptown Girl together.

Last weekend, they met again during rehearsals for the Grammy ceremony, and chatted briefly. “I was asking how long it’s been since you put out a song,” says Rodrigo. “Well, they’ve released recordings that I’ve made, but I never meant for them to be released,” responds Joel. “But even that was 17 years ago,” adds the person recording the meeting, apparently Wexler.

Rodrigo belongs to a generation that has discovered Joel decades after he was one of the pillars of the recording industry, and it has done so with an unbiased fervor that has surprised many Boomers. It is this generational shift among Billy’s cadre of followers that explains why one of his most popular songs at the moment, with more than 474 million plays on Spotify, is Vienna, a song that was not even among the five singles of the album on which it was released, The Stranger. Its appearance in viral videos on TikTok has had the effect of turning this hidden gem into a late-blooming classic, an artifact that went unnoticed in its day and today, has triumphed against all odds, in a very different world and among the most unexpected audience. Joel is now in the 218th position of most listened-to artists in the world on Spotify, rising above many youthful bestsellers.

Something similar has happened with Zanzibar and Movin’ Out (Anthony’s Song), which were propelled by the Chinese social media platform’s algorithm and are now installed at the top of the Billy Joel songbook as listened to by people under 20 years old. Not bad for a man who put out his last album shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, and who has been surviving fame ever since with remarkable dignity, and without success ever turning its back on the Joel legacy.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.