Researchers unveil the mysteries of the Florentine Codex

The Getty Research Institute digitized and translated the 12 books, providing a fresh perspective on the Spanish conquest of the New World

The Florentine Codex, written nearly 500 years ago, continues to reveal hidden secrets and share knowledge about the Indigenous peoples who experienced the fall of Tenochtitlan in the 16th century. It is widely regarded as the most reliable source on Mexica culture, the Aztec empire and the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in what is now Mexico. Previously untranslated Nahuatl texts could potentially reshape the narrative of the Spanish conquest, offering intriguing insights into historical events and perhaps prompting a reevaluation of certain episodes.

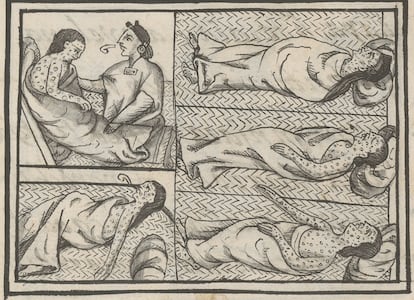

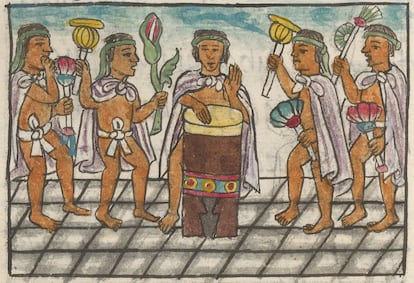

A team of 68 researchers, scientists and linguists spent seven years digitizing and translating the nearly 2,500 pages of a manuscript into modern Spanish, English and Nahuatl. Now available online, the project showcases the original Spanish and Nahuatl text, along with over 2,000 hand-painted illustrations. Funded by the Los Angeles-based Getty Research Institute in collaboration with the Laurentian Medici Library in Florence (Italy), “the Florentine Codex is considered the most important manuscript of the 16th century and a significant Indigenous encyclopedia of its time,” according to project leader and Mesoamerica expert Kim Richter.

The Florentine Codex is a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by Bernardino de Sahagún, a Spanish Franciscan friar who dedicated most of his life to documenting the Indigenous peoples of Mexico. Indigenous elders, Nahua philologists, scribes and artists called tlacuilos collaborated with the friar to write and illustrate the 12 books (in three volumes) that make up the Florentine Codex. Some of Sahagún’s collaborators include Antonio Valeriano, Alonso Vegerano, Marco Jacobita, Agustín de la Fuente and Pedro de Sanbuenaventura, trilingual students from the Colegio de la Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco (modern-day Mexico City). After its completion, the manuscript was sent to Europe and eventually ended up in the Medici family library in Florence, hence its name.

The Florentine Codex has been available on the World Digital Library since 2012, but could only be understood by people with extensive knowledge of 16th-century Nahuatl and Spanish. The manuscript spent centuries in oblivion, despite being a bilingual primary document of unique significance. Written in parallel columns of Nahuatl and Spanish, most of the initial focus was on translation of the Spanish portions of the text. “Books 1 to 11 still need to be translated from Nahuatl, a project that began at UNAM [National Autonomous University of Mexico] and is still ongoing,” said Richter. “Berenice Alcántara and Federico Navarrete are now translating Book 12, although I would have loved a Nahuatl translation of all the books.”

Richter believes Sahagún based some of his work on the five letters that Hernán Cortés wrote to Spain’s King Charles V to report on the conquest of Mexico. She says a comprehensive understanding of all three accounts (Spanish, Nahuatl and the illustrations) is necessary to fully comprehend the old codex because the narratives of the conquerors and the conquered are often quite different. “The Nahuatl and Spanish texts don’t say completely different things, but the way they present that history is very different.”

Richter noted that in Book 12, which focuses on the conquest, the Spanish text is written in spare and factual prose. For instance, it provides a short description of how Montezuma’s surrendered without much resistance. “The Nahuatl text describes how the capture of Moctezuma, Itzcuauhtzin and the other Aztec leaders was quite violent. It suggests that they were imprisoned and killed by the Spanish,” said Richter. “The Nahuatl text actually tells the story of that invasion and war in a more poetic way. It doesn’t mention the Indigenous Spanish allies, but rather focuses on how the Tlaxcalans were betrayed.”

One of the illustrations shows the Spanish throwing Moctezuma’s body into the water, a detail that caught the attention of the research team. “In book 12, all the images are black and white. However, the artists used a hint of color to highlight certain images and capture the reader’s attention. They subtly addressed certain passages, like Moctezuma’s death, with caution due to Spanish rule. However, their intention to recount that historical event is evident,” explains Richter.

The research team also attempted to identify all the contributors to the codex apart from Sahagún. The texts originated from many conversations between Sahagún and Indigenous elders that were documented by his Indigenous students, notes Diana Magaloni, director of the Ancient Americas Art Program at the Los Angeles Museum of Art. “We have identified the distinct styles of all the Indigenous artists and scribes,” said Richter. “Sahagún doesn’t provide the names of all artists, and only mentions three scribes. But we now know there were nine scribes, and some could both write and illustrate.” The research team identified 22 different artists who created the illustrations.

All of the Indigenous scribes and illustrators were young monks attending the Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco school. “Many of them were children of the Nahuatl elite and received a humanistic education influenced by the new trends in Europe,” said Richter. Educated at the University of Salamanca in Spain, Friar Bernardino de Sahagún was charged with training future Franciscans who would master Nahuatl and evangelize in that language. “That kind of thinking changed by the end of the 16th century. Books in Nahuatl were no longer produced because Spanish institutions realized they couldn’t control the narrative.”

Experts believe that the authors of the Florentine Codex likely contributed to other historical accounts, such as The Annals of Tlatelolco and the Aubin Codex. “Aubin mentions and depicts Antonio Valeriano, one of Sahagún’s collaborators,” said Richter. “He was one of the most knowledgeable scholars of that time.” Like modern encyclopedias, the Aubin Codex covers various topics, including some beyond Mexica society, from the perspective of Tlatelolco, the town where it was written.

The significance of the Florentine Codex today

The influence of the Florentine Codex on modern-day Mexico remains significant. However, the historical narrative taught in classrooms often depicts Indigenous peoples as a relic of the past, stereotyping them as naive, feeble and childlike individuals easily conquered by the Spaniards, or as treacherous, violent and malevolent people who collaborated with the Spaniards and betrayed their own.

At a 2019 conference in Zacatecas (Mexico) scholar Eduardo de la Cruz explored these two stereotypes of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples. De la Cruz translated some of the classic Nahuatl text in the Florentine Codex to a modern form of the language spoken in the Huasteca region. He shared them with secondary school students from El Tecomate, Veracruz, who were exposed to a different version of the Spanish conquest for the first time. “They were impressed that the Mexicas fought and defended their empire up until [Aztec ruler] Cuauhtémoc was defeated,” said De la Cruz.

Despite the fact that this historical account has been around for five centuries, they were never taught about it in school. “The government lacks didactic materials on the Spanish conquest that highlight Indigenous resistance. Despite this, Indigenous peoples persist today, fighting for their rights and promoting their language and cultural wealth,” said De la Cruz, who emphasizes the importance of ensuring that such documents are publicly accessible. “Especially for communities that have a connection to this history.”

“It’s a debt that we still owe to the Nahuas and their language,” said Richter. De la Cruz goes a bit further. “Changing the way younger generations perceive Indigenous peoples helps them connect with their ancestors and take pride in their Indigenous roots, rather than feeling ashamed of them. And if they show interest in learning, writing, and speaking Nahuatl, the language will thrive and evolve, just like Spanish and English do.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.