Munch, the wizard from the North who transformed angst into art

Two exhibitions in Berlin and Potsdam evoke the impact caused by the visionary author of ‘The Scream’ and his influence on 20th-century art

The first time that a then-unknown Edvard Munch exhibited his paintings in Berlin on the invitation of the city’s Artists Association, in November 1892, the impact was so great that the exhibition had to be cancelled after a week. The Berlin public was fascinated by all things Scandinavian, with its natural landscapes of snow-capped mountains, frozen lakes and majestic fjords. But what the young Norwegian now offered them were paintings with nervous, almost schematic strokes, with fluid shapes in intense colors, and it was altogether quite disturbing. Munch turned out to be too radical for Berlin’s conservative art scene.

The impetus that Munch had given to art, however, would be unstoppable. Fed by the Franco-Belgian symbolism that he had absorbed in Paris, his work imposed a change in perspective: instead of capturing impressions of nature, he wanted to express the primary emotions of the individual. The young painter savored the scandal of his cancellation in Berlin. “It’s the best thing that could have happened to me. I couldn’t get better publicity,” he wrote proudly in a letter to his family. And he was not wrong: the exhibition returned to the German capital shortly after and, the second time around, it was a success. His fame would grow to consecrate him as one of the greatest avant-garde exponents of experimental art of the 20th century.

On the 160th anniversary of the birth of Edvard Munch (1863-1944), two exhibitions in Berlin and Potsdam celebrate the work of the Nordic genius, pioneer of experimental art that would break out in the first decades of the new century. “Munch’s works were so avant-garde and foreign to Berlin in 1892 that they hit the art world like a meteorite and shattered it,” summarizes art historian Stefanie Heckmann, curator of the exhibition Edvard Munch. Zauber des Nordens (Magic of the North), at the Berlinische Galerie in the German capital: “It was the beginning of modernism in the city and of the artist’s international career.”

The exhibition welcomes visitors with a placid realist landscape of the Lofoten Islands (1891), by the painter Adelsteen Normann (1848-1918), a favorite of Emperor William II and godfather of Munch, to give an idea of the contrast between the naturalistic Scandinavian painting that triumphed in Berlin at the time and the revolutionary proposal that Munch presented, which forever disrupted the utopian image of Scandinavia. The exhibition highlights the artist’s connection with Berlin, where he refined his works. There are 90 pieces by the Norwegian artist on display, some well-known such as Love and Pain (Vampire) or Madonna, in a retrospective that is perfectly complemented by the Barberini exhibition in Potsdam and allows viewers to enjoy in total of more than 200 works by Munch, something quite exceptional outside of Oslo.

For Munch, nature was a mirror of his inner turmoil, which gave his landscapes great drama. This is the focus of the Lebenslandschaft (Landscapes of life) exhibition at the Barberini museum in Potsdam, which brings together 116 paintings, drawings and lithographs from around 20 museums that show how the artist transfigured Nordic landscapes to project upon them his deepest moods. “Nature is not only what is visible to the eye; They are also the interior images of the soul,” he wrote.

Although the painter dedicated almost half of his works to motifs from nature, until now he had not been considered a landscape painter, explained Ortrud Westheider, the museum’s director, during the presentation of the exhibition in Potsdam, which was previously on display at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown (United States) and will travel to its third location, the Munch museum in Oslo, in April 2024. “We wanted to open that perspective of his work for the first time,” revealed Westheider, accompanied by curator Jill Lloyd and Munch Museum director Tone Hansen.

The exhibition covers the natural environments that Munch reflected: the forests, which for him were a source of mystery, as in Winter Night (1900), and the coasts, which he identified as the “lines of life in perpetual change,” as in Summer Night on the Beach (1902/03), and which usually appear in his scenes about melancholy, isolation and separation. Munch also emphasized the unity between human beings and nature. The Barberini exhibition showcases this by bringing together in the same room a lithograph of The Scream —difficult to see outside of Oslo; the curators said that it was the last loan to be confirmed—, and its nature in full turmoil, with the monumental The Sun (1911), made for the ceremonial hall of the University of Oslo, which gives off positive energy, with the star shining in all its splendor as a provider of life.

The two institutions have taken advantage of the weeks in which the exhibitions coincide to create a joint ticket for €20 that facilitates the experience of enjoying so many works by the Norwegian genius at the same time in Germany. Munch’s relationship with the country was definitive for his international takeoff. Between 1892 and 1908, the cosmopolitan capital of the German Empire was his residence for several seasons. There he drank in its intellectual atmosphere, especially in the tavern Zum Schwarzen Ferkel (The Black Piglet), on the boulevard of Unter den Linden, where the Swedish playwright August Strindberg and the Norwegian poet and pianist Dagny Juel, who was Munch’s muse, were regulars. In that environment, influenced by Nietzsche’s thought, Munch elaborated on the concept of the heroic and creative individual who frees himself from religious, moral and social constraints to create his own reality.

The Berlin exhibition exhibits one of the variations of Melancholy (1891), which was shown in that controversial first exhibition and describes one of its most famous themes. In it, the sadness of the young man in the foreground seems to be projected onto the beach in the background, blurring the profiles of the shore, the waves and the rocks, in a convulsive whole of graphite, colored pencils and oil strokes, impetuous and unfinished. It is an example of how he distanced himself from that naturalism that copied nature: “We cannot surpass nature. It is better to describe emotions; those of oneself,” Munch wrote.

Munch wanted to probe the most intense human sensations: “A work of art comes only from the depths of the human being,” he noted. For this, the most fashionable art, such as naturalism and impressionism, were of no use. “I started out as an impressionist, but during the emotional and existential conflicts of my bohemian period, impressionism no longer provided sufficient expression. I had to find a style to express what moved my mind,” he explained in one of his notes.

Among the sensations he sought to reflect, angst stood out, a Germanic word that combines the senses of anxiety, anguish and fear, which was the common denominator of much of his work. Munch was burdened by a tragic family history after losing his mother as a child and his sister as a teenager, both victims of tuberculosis, and he considered fear, anxiety, and threat as formative and fundamental human experiences. The language to express these elementary emotions would be the myths of symbolism, such as the kiss, the vampire, jealousy, despair and death.

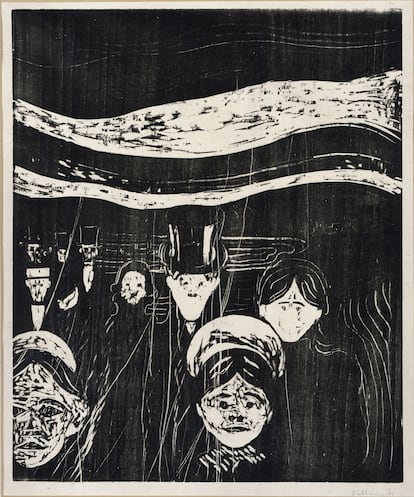

In the exhibition, this feeling of fear emanates from works such as Angst (1896), a woodcut that belongs to the same cycle as the famous The Scream (1893), and which shows a group of bourgeois people looking expectantly at the observer, surrounded by an undulating and ominous sky. The oil painting Love and Pain (Vampire) (1916-18) depicts a sinister atmosphere where the reddish hair of a female figure hugs the head of a defenseless man like a jellyfish. In Madonna (1895), a pale, naked woman seems to blend into a dark background of vibrant, sinuous lines. In other scenes loneliness and isolation are imposed, as in Two Human Beings: The Lonely Ones (1896), and in The Dance of Life (1899). Munch considered that his scenes about primary emotions were best understood grouped together, and thus conceived the idea of exhibiting them in series such as his magna The Frieze of Life.

Munch’s explorations of psychology and nature were highlighted in the great retrospective that Berlin gave him in 1927, when he was already in his sixties and crowned the father of avant-garde movements such as expressionism. His connection with the capital covered 60 exhibitions from the scandal of 1892 until the arrival of the Third Reich in 1933. Munch, although he had lived in Norway since 1909, was an uncomfortable figure for the Nazis, as he was the incarnation of the Nordic genius, but at the same time his art was declared “degenerate.” In April 1940, when Nazi troops occupied Norway, Munch avoided contact with them and isolated himself on his farm outside Oslo. Upon his death in 1944, he donated all of his work to the city of Oslo. A legacy that, with its starting point in Berlin, transformed the image of the North and left an indelible mark on universal art.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.