Biography of David Koresh, the rocker who wanted to be a messiah

Stephan Talty’s undaunted portrait of the leader of the Davidians joins the list of classic books on Charles Manson, Jim Jones and other apocalyptic cult leaders

It was a slaughter in full view of the whole world. During the siege of the Davidians’ stronghold in Waco, Texas, in early 1993, some 1,000 journalists arrived, including television crews. Even so, the causes of the fire that, on April 19, resulted in the death of most of those under siege at the Mount Carmel compound are still being debated. This was not the intention of the besiegers, who were aware of the presence of many children: tear gas was used, hoping that they would leave. Stephan Talty, who has listened to hours of recordings from both sides, argues that at least some of the fires were set from inside, by fanatics who then shot at each other.

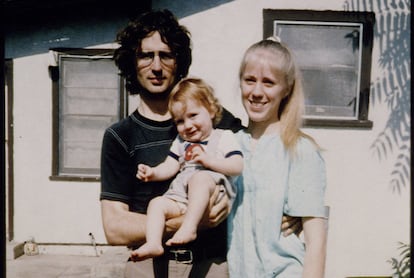

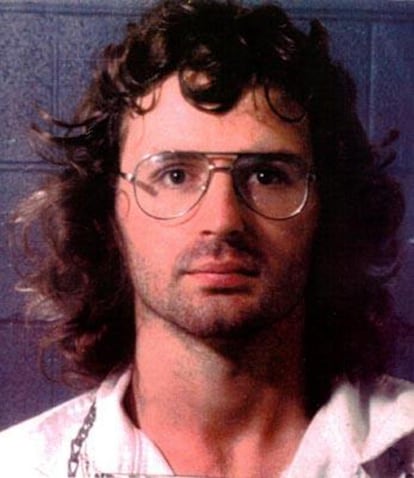

In Koresh, Talty picks up the narrative lessons of Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song. An Irish-American, he has enough perspective to highlight the particularities of David Koresh, an anomaly even in such hyper-individualistic territory as Texas. He survived a cruel childhood to become a rock guitarist, with a devotion to Eric Clapton, Steve Vai or Ted Nugent. However, he concluded that the business of religion was more profitable: astute and charismatic, he took control of the Branch Davidians, an offshoot of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. He enjoyed a comfortable economy and had the right of sexual intercourse over the females of the congregation, including minors. His libidinous plans included Madonna; he intended to seduce the singer and then redeem her.

But what troubled the authorities eventually was the stockpiling of weapons. Like millions of Americans, the Davidians believed that the end of the world would be preceded by a literal battle in Israel between believers and the armies of evil. The plan to move there met with the refusal of the Israeli state, which has a protocol against “Jerusalem Syndrome” sufferers — that is, Christians who come to the Holy Land and, intoxicated by the experience, believe themselves to be (and proclaim themselves to be) messiahs. Koresh then decreed that Armageddon would occur in the United States itself. His faithful were subjected to military training and war movie sessions. They also went to arms fairs to sell military equipment and a line of clothing made by the women of Waco, David Koresh Survival Gear. In the face of their increased activity, the only complaints came from Marc Breault, a disappointed supporter. And the suspicions of a UPS deliveryman, alarmed at the deliveries of assault weapons and grenade-making equipment.

The Koresh case ended up under the jurisdiction of the AFT, the federal bureau that oversees the enforcement of alcohol, tobacco, firearms and explosives laws. The AFT had a reputation for violence but lacked insight. Their shortcomings became apparent in 1993: they could have stopped Koresh as he moved through the streets of Waco but opted for a “dynamic assault,” a frontal attack on the Davidians’ compound. The Davidians, already forewarned, had more firepower and stopped the onslaught. Six Davidians and four federal agents were killed.

The FBI took charge of the matter and did not shine either. There was great tension between the negotiating team and the strike groups: their bosses wanted to shorten the wait, claiming that their men had training commitments. In the impasse, Janet Reno was appointed as Attorney General and, despite President Clinton’s reluctance, she agreed to have the shut-ins gassed: she was very belligerent against child abuse.

Given the brutal outcome — 76 victims, of whom 28 were children — it is surprising that the extreme right has not made more of the Waco tragedy. David Koresh may not fit your typical hero mold: he was not a racial supremacist, he rejected xenophobia and, as has been noted, he was a sexual predator. But there was someone who decided to avenge him. Timothy McVeigh, a former soldier, went to Waco during the siege to assert the right of every citizen to bear arms. Exactly two years to the day after the massacre, he detonated an 8,000-pound bomb in an Oklahoma City building housing the headquarters of the AFT and other federal agencies. 168 people died, including many of the children in a day care center.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.