Bill Watterson’s return after ‘Calvin and Hobbes’ adds mystery to his legend

In a major event in American comics, after nearly three decades of silence, the cartoonist returns with ‘The Mysteries,’ a laconic black-and-white fable done in collaboration with cartoonist John Kascht

Writing 43 sentences doesn’t seem like the most loquacious way to break almost 30 years of silence. But you never know with Bill Watterson, the creator of Calvin and Hobbes, one of the most beloved newspaper comic strips in history. The cartoonist just published The Mysteries, a laconic black-and-white “adult” fable based on Watterson’s story with drawings done in collaboration with John Kascht, known for his elongated caricatures of celebrities.

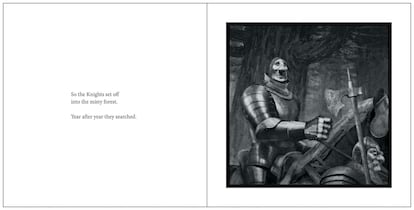

The Mysteries is the story of a medieval kingdom in crisis, with airplanes flying over newspaper stands and highways, where life is shaped by “the mysteries” alluded to in the comic’s title. “No one had ever seen them, but they seemed to be everywhere. And people lived in suspicion and fear,” the fable begins. Printed on the odd pages of the hardcover book, the drawings are intriguing, a mix of charcoal backgrounds and what looks like photographs of clay models. The 43 sentences construct a morality tale that is open to interpretation. Is The Mysteries a reflection on climate change? Or is it about immigration? Does it talk about the lies of power? Or the dark side of technology? With Watterson, you never know.

Watterson, 65, was born in Washington but soon moved with his parents to Chagrin Falls, a small town near Cleveland, Ohio. The area’s wooded charm served as the setting for the comics he began publishing in 1985. His characters were a bold, imaginative and intelligent six-year-old boy named Calvin and his inseparable conspiratorial friend Hobbes, an extremely sharp animal or a stuffed tiger, depending on how you look at it.

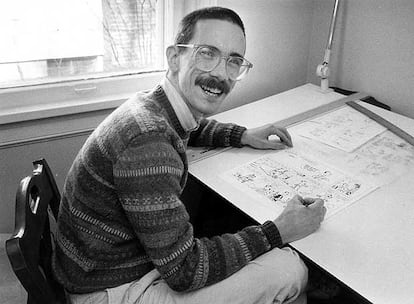

In 1995, Watterson published the last comic strip, in which Calvin uttered one of the most famous lines in the history of comics: “It’s a magical world, Hobbes, ol’ buddy… Let’s go exploring!” Since then, the cartoonist has devoted himself to his own pursuits: cultivating his passion for music, spending time with his family, sabotaging his bank account by refusing time and again to turn his characters into merchandising fodder, and avoiding the spotlight. Like a comic yeti, the same photo of him is almost always in circulation; in it, a smiling Watterson looks up from his worktable. (In recent weeks, some critics have wondered whether the new work might not be a cryptic account of his retirement).

Watterson hasn’t been completely silent in the nearly 28 years since he left Calvin behind. While he declined to appear in a documentary about him (Dear Mr. Watterson, 2013, available free on YouTube), he has given at least three interviews: one to his hometown paper, the Cleveland Plain Dealer, in 2010, in which he stated that he has never regretted the decision to retire his characters; another to the curiosity website Mental Floss, in 2013; and his most in-depth interview, done on the occasion of the publication of a catalog for an exhibition on his work in 2015. He drew the poster for a documentary on the evolution of newspaper comic strips (Stripped, 2014) and, eight years ago, he also created the poster for the Angoulême festival, which awarded him the Grand Prix for his entire career. In addition, he left his refuge to honor another master American cartoonist, Richard Thompson (1957-2016), the creator of the unforgettable Cul de Sac, and somewhat unexpectedly collaborated with the Pearls Before Swine comic strip.

Thompson was the one who introduced Watterson and Kascht. The Mysteries is the fruit of a decade of collaboration between the two. The February announcement of the project’s existence caused a great stir. After the book’s publication, Watterson made an exception to his silence by releasing a 15-minute promotional video in which the two authors take turns describing the half-finished work in a voice-over.

Watterson wrote the book’s story, which he says he had kept in a drawer for a long time. They imposed a rule on each other: “Neither of us would have the last word. Neither could veto anything or cancel the project. We would only go ahead with what we agreed on,” the creator of Calvin and Hobbes says in the video. As he speaks, images of hands — apparently his own — working on one of the comic’s backgrounds appear on screen. Watterson adds that he “wasn’t looking for an assistant. I didn’t want to be the boss. I wanted a sparring partner, someone whose ideas and skills challenged my own.”

Both describe the struggle between a perfectionist who needs to know where he’s headed at all times (Kascht) and someone who loves improvisation (Watterson). “It would be hard to overstate the incompatibility of our creative approaches,” the former explains in the video. “Now I understand why [rock] bands break up in the recording studio. Our collaboration wasn’t so much a matter of compromise as it was a matter of clashes. It didn’t end up being very smart: we created tons of waste. The truly remarkable thing is that we never got personally angry. We worked from a point of difference in pursuit of a common purpose, which is almost an act of defiance these days.”

Starting over

Watterson recounts that by the end of the first year they hadn’t been able to produce anything together. “So, we started over,” he adds. Kascht created a bunch of clay models of faces of inhabitants of that medieval world and sent them to his partner. They did something akin to casting the models. Nevertheless, the story had a happy ending for Watterson, who concludes in the video: “Collaboration creates friction, but it also creates energy, and sometimes the combination of talents is greater than the sum of its parts.”

The result of that partnership is a strange artifact, which has been received as a disconcerting event in the world of American comics. It has done well on bestseller lists because of the legendary comic strip that was published every week in over two thousand newspapers around the world, including EL PAÍS, but it has disappointed those who expected some trace of the joy and lightness of Calvin and Hobbes.

In a 2010 interview with the Plain Dealer, 15 years after the end of Calvin and Hobbes, Watterson stated, “It’s always better to leave the party early. If I had followed the strip’s popularity and repeated myself for another five, 10 or 20 years, the people who are now mourning Calvin and Hobbes would be wishing me dead and cursing newspapers for publishing tedious, old strips like mine instead of bringing in fresher, livelier talent. And I would have to agree.” Watterson also left another party — paper newspapers — early (or at the right time), although some like The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times continue the tradition of publishing an offprint on Sundays with comic strips on top of each other, a format that is difficult to translate to a webpage.

To return to the imaginative universe of the boy named after a certain reformist theologian and the tiger inspired by Thomas Hobbes, one must go to the Billy Ireland Comic Book Museum and Library at Ohio State University in Columbus, which houses “the world’s largest collection of cartoons, graphic novels and comic-related materials.” That includes 3,000 originals of the famous comic strip, which Watterson deposited there. In addition to the exhibits, visitors are welcome in the reading room, where they can consult materials from the library’s inexhaustible holdings.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.