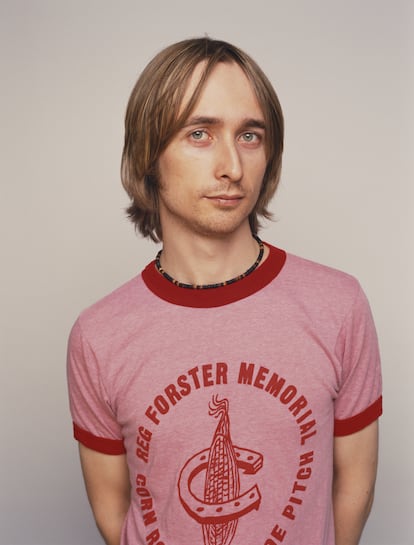

Neil Hannon: ‘I was prepared for my fans to say my last album was shit’

The front man of The Divine Comedy is a sarcastic, music-loving, and unprejudiced Irishman who has been making whatever music he wants for 30 years. This Saturday he will play live at the Canari Festival in Spain’s Canary Islands

Founder and plenipotentiary front man of The Divine Comedy (in fact, the ensemble has long been his one-man project), Neil Hannon has built a well-deserved reputation as one of the finest craftsmen of baroque and orchestral pop. Hannon began his career in 1989, although he had to wait until his band’s fourth album, Casanova (1996), which included singles like Something For The Weekend and Becoming More Like Alfie, to achieve massive success in the midst of the Britpop explosion. Fame did not last long: his songs, full of beautiful string and woodwind arrangements and nods to the musical traditions of continental Europe, were not a good fit for a scene that sometimes tended towards an overexuberant expression of Britishness.

Hannon continued doing his thing, releasing albums regularly — there are 12 now: the last one, Office Politics, dates from 2019. He built up an amazing list of collaborators (Tom Jones, Air, Ute Lemper, Robbie Williams, Yann Tiersen, and Coque Malla), and collaborated himself on a multitude of soundtracks for television series and films. The next one will be Paul King’s Wonka (released December 6), with Timothée Chalamet in the lead role as the crazy chocolatier from Roald Dahl’s famous novel.

After the compilation album, Charmed Life (2022) and the subsequent tour, The Divine Comedy will perform at the Canari festival in Lanzarote on November 18 — the only date the band has scheduled for the remainder of 2023. There, this former dandy with an elusive figure will share the stage with Maika Makovski, Melenas, and The Parrots. The Canary Islands concert is the fifth location in the itinerant Festivals for a Territory multidisciplinary event that includes gastronomy, art, and music, and is committed to decentralizing culture. It is the perfect excuse to chat with the man who wrote National Express, and who is a master of irony and self-deprecation. It’s a wet and gray Irish day, he laments as soon as he connects the video call from his home in County Kildare, surrounded by his synthesizers and keyboards.

You were born in Derry in the 1970s, the decade of Bloody Sunday and the Troubles. What was your childhood like there? The truth is that I haven’t thought about that in a long time. It’s funny... I guess, in a way, all of that made me the kind of person I am. Ours was quite a sort of middle class family, although without much money. My father was a Church of Ireland minister and we lived in a nice red brick Victorian terraced house, but we didn’t go to Spain on holidays (he laughs).

Was pop a kind of refuge? Before I was a teenager I liked music, but I didn’t think I was going to do it as a job. In fact, I thought I was going to design sports cars. Then I became obsessed with Top Of The Pops, the famous BBC music show. I watched it every Thursday from the age of seven and then I started listening to the radio. I remember that certain types of music scared me, it had a visceral effect on me. The first time I heard Under Pressure, by David Bowie and Queen, I was quite scared. Now I adore it. And I think that fear was a good thing, because it was like I was being challenged by this music. It was so different from the bubblegum [the catchiest and most commercial pop music] that was around at the time. I was too young for punk, but I caught the end of New Wave and I started liking Elvis Costello and early XTC, although I was not a die-hard fan. What I really loved was synth pop: Ultravox, The Human League, OMD, and Soft Cell. I became very obsessed by that. And I think that kind of shows in my work. I have never used many synthesizers, but, the tunes and the way the songs are constructed are very present in my work. And all the time, the world around us was completely crazy around us. Northern Ireland was not a pleasant atmosphere to grow up in.

I read that as a teenager you were a big fan of ELO (Electric Light Orchestra) and Jeff Lynne. I don’t know if it was before or after the synth pop stage. It coexisted. I have two older brothers and Desmond, the oldest, started listening to ELO. And I listened to whatever he liked. Please don’t tell him I said this, but it was an unconscious thing. In many cases I wasn’t even a fan, I just consumed the music. It has a lot to answer for in my own music: the keyboards, the strings, the choirs...

What was the album that changed your life at that moment? There are so many pivotal records, but, if I had to choose one, I would say the single Vienna (1981), by Ultravox. It was the first single I bought and I must have listened to it a thousand times. It is classic synth pop, but it is also highly classical music in its structure and its overtones, with the electric viola and that Rachmaninoff style piano. I have always been attracted to the idea of making pop that in some way sounded like classical music.

You formed The Divine Comedy in 1989. I guess it was not easy to start and band and have immediate success. I come from a family where these kinds of things could be done. Most of my closest relatives would have gone to university or done interesting things, so I feel lucky that I was never dissuaded from following my path. My parents worried about what was going to happen to me, of course. I am the youngest of three and the other two studied at university and did well. So, when it was my turn, my parents didn’t have much energy left.

Right now you have a solid career, but do you think that if you had started in 2020 everything would have been more difficult? Obviously, people starting in 2020 have had a totally different life experience, starting with the music they listen to. The truth is that I feel sorry for those who are starting now. This is a very difficult industry and social media can easily hurt you. Now you can upload your songs to Spotify instantly, without problem, but they have to rise above the rest. It must be very difficult to be different enough. And with the rise of things like TikTok, you’ve only got about 40 seconds to hook the audience, and I need at least three and a half or four minutes. Luckily, I don’t have to worry about that anymore.

What are your memories of the Brit pop era during the nineties? Did you feel part of that scene? If I’d been more successful, I would’ve been a proper Britpop artist. I was in the background and there were a few moments of real fame. And then I’d just disappear again because there were so many amazing, huge acts that were much more connected to all that: Blur, Pulp, Suede, and all the rest. My fans may have been alarmed when I wrote about this for Casanova’s thirtieth anniversary, but when I was writing that album I saw which way the wind was blowing, musically and artistically speaking. Listening to Suede, The Auteurs, and Saint Etienne were a big deal to me. I noticed the integration of the cool easy listening sound and the soundtracks of the 1960s, stuff like John Barry and Ennio Morricone. And I loved that music. So I thought: I can do this! I’m going to do something that’s alarmingly popular!

Did you enjoy that fleeting massive success? We did some really big gigs, got really high on the charts, and played on Top Of The Pops. All my dreams came true, but I was never invited to the parties.

Since 2020 you have been re-editing and remastering your entire discography. Are there any of your albums that you wouldn’t mind recording again? No. I’ve never wanted to do that. It doesn’t make sense, because as soon as you release a record, it no longer belongs to you, it belongs to the audience, and they layer meaning onto your work. They decide how it should sound in their heads. And going back and re-recording something is like an act of sabotage to their imagination. I know how it feels when one of the artists I admire has done something similar.

Like who? I’m not going to give an example. I don’t want to alienate some of the people I love the most (laughs). Well, I’ll give an example with one of my three favorite artists of all time: Kate Bush. For me she’s at the top, but she re-recorded Wuthering Heights. And it doesn’t make any sense. It doesn’t have the same vibe or soul that the original had. It’s not her fault. She has gotten older and used different instruments and equipment. I listened to that song constantly for eight years and I didn’t care what she thought about her song, I only cared what I thought.

Your last album, Office Politics (2019), meant a change in sound, even adding electronic touches. And it was also a shock to some of your fans. The truth is that I was prepared for my fans to say it was shit. It’s very important for me not to think about the fans when I write music. I didn’t think about them when I recorded my first albums, mainly because they didn’t exist. Why should you keep regurgitating something because you think that’s what they like? I don’t understand. I don’t mind selling fewer records, but I hope that my followers appreciate that I’m following my own artistic principles.

Many people still think of Burt Bacharach and Scott Walker when talking about The Divine Comedy. The two of them still represent a large part of my writing technique. The things you have heard over the years eventually come out all mixed up in your work. And I will never be free of singing like Scott [he says it singing in the manner of Scott Walker] and I will always owe a lot to Burt’s intelligent and beautiful structures. I feel very lucky to have met them both, even if briefly.

I'm not going to ask you about the classic debate between The Beatles or The Rolling Stones, but rather The Beatles or The Beach Boys? Because he mentions both groups in his song Perfect Lovesong. I greatly admire the Rolling Stones, although I was never a big fan, I was never a rocker. The other day I was listening to Street Fighting Man and his songs from that time are incredible and splendidly recorded. Just like Gimme Shelter. But I will always be on the side of The Beatles or The Beach Boys.

And between The Beatles and The Beach Boys? The Beatles. They are a kind of first love. And then there is the strength of numbers. The Beach Boys’ best songs are as good as The Beatles’ best, but they just don’t have as many.

And The Kinks? I have always felt a connection with their works. I bloody love The Kinks! The Village Green Preservation Society is a fantastic album, but I like their earlier stuff as well. I’ve been a fan of pop for a long time and I like stuff that is just for the sake of excitement.

I'd swear he's not the biggest fan of reggaeton... Curiously, no. I tend to like the top 10% of any genre. I'm not against any particular style. I'm not a big country fan, but I like Johnny Cash, for his more alternative side, or Dolly Parton, for her pop side.

Together with your partner, singer Cathy Davey, you sponsor the animal rescue organizations My Lovely Horse Rescue and My Lovely Pig Rescue. I think your song To The Rescue is based on this experience. One of the shelters is 20 minutes away from our house... and the other is our house.

Really? Which? The one with the pigs. Where we live we have about 120 or 130. They were all pet pigs, they are not rescues from farms or anything. There are silly people who buy piglets thinking that they will stay like that forever. And no, mini pigs do not exist, they all grow. The truth is that I don’t take care of them much: I love seeing them and spending time with them, but I’m not the one feeding them. I take care of our four dogs. We also have donkeys, sheep, goats, chickens, and the occasional rat.

By the way, have you seen the series Derry Girls? Yes, it's fun. Although it seems to me that it is designed for the British market. The Irish also like it, but it is not too close to the reality of those years. That would have been pretty depressing.

The Derry accent difficult for non-English speakers… It is quite difficult to understand [imitating a strong Derry accent].

Maybe a similar thing happens with your songs outside of English-speaking audiences. There are those who don’t understand the lyrics and still love the songs. I have a show on BBC Radio Ulster [called Europop: The Neil Hannon Show] and I only play continental European music there, no British or Irish stuff. They are all French, Italian, Spanish, German, or Scandinavian songs. And many times I don’t understand anything they say. But it doesn’t take away from how much I love them. So I understand that feeling: you feel like you know what they’re talking about, but there’s a lot of room for the listener’s imagination. You can search my lyrics and see what they are about, although it is not necessary. Most of them are rubbish (laughs).

In the deluxe edition of your recent compilation, Charmed Life, there is a song titled I love you Spain. In it you sing about red wine, ham, tortilla, paella, Padrón pepper, and Manchego cheese (sic). I have to sincerely apologize for that. It was during the pandemic and it was for a fake Eurovision Song Contest [the Isolation Song Contest]. Most of the other contestants were comedians and I still went for it. They told me: Make a song. Your country is Spain. So they were the ones who assigned me the country. I thought, cool, I’m going to include all the Spanish Eurovision entries that I remember. And it’s a complete cliché, I know. Although it satirizes that narrow and stupid idea of Spain that some British and Irish people have: going on vacation there, drinking beer, eating paella and getting sunburned.

At least you can try some of those products now that you visit Lanzarote. Well, I’m a vegetarian. But yes, I love Spain [in Spanish].

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.