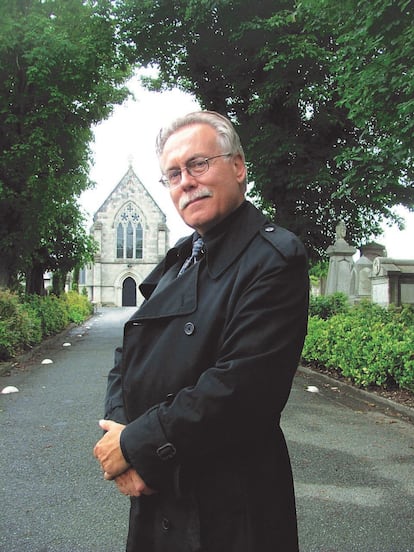

David J. Skal, a life spent analyzing nightmares

The film critic is presenting a new edition of his classic book, ‘The Monster Show,’ where he analyzes the cultural history of terror. He explains that each era creates its own monsters

In 1993, the American critic David J. Skal analyzed in his book Monster Show the creatures that emerged from the cauldron of humanity’s collective hysterias, threats and nightmares through cinema, from its beginnings until the 1990s. From its first edition it was a resounding success. And it continues to be so. So much so that last week he visited Spain to present the reissue of that work by Es Pop Ediciones, celebrate three decades of the volume and chat with the press.

When asking Skal about who he is, he defines himself, even at 71 years old, as a monster kid. “Monster child” is also how figures such as Stephen King, Guillermo del Toro, Peter Jackson, Joe Dante, John Landis, George Lucas and or J. J. Abrahams have called themselves. Skal is still enthusiastic, as if for the first time, when he talks about the films covered in Monster Show, which continues to be reissued around the world: “It has never been out of print since it was first published in 1993″. His essay covers terror decade by decade, starting with the French Grand Guignol shows and their decline when the soldiers return from the front in 1918. They returned alive thanks to penicillin, but they do so mutilated and disfigured by the weapons of the industrial era. Skal attributes to this army of the living dead (those known as gueules cassées) the public’s disinterest in the horrors that were staged through tricks and phantasmagoria in the Parisian neighborhood of Pigalle.

At that time, the first theatrical adaptation of a creature born at the same time as cinema also took place. Dracula has been another of Skal’s obsessions, the subject of his first essay, Hollywood Gothic. “I became interested in Dracula again during the AIDS epidemic, where everything was a reminder of the contamination of blood,” he says. Hollywood Gothic is a piece of research that took him years, and in which he explains the intricate history of the adaptation of Bram Stoker’s classic: economic interests, legends, mismanagement, the configuration of cinema as the seventh art and, of course, explanations for phenomena such as George Melford’s Dracula (shot at night on the same sets as Tod Browning’s version starring Bela Lugosi). “That film was filmed because the co-producer of Dracula was in love with Lupita Tovar, and she did not have any project in Hollywood. He wanted to prevent Lupita from returning to Mexico at all costs, so he raised this strange version so he could continue haunting her. And he did it, they got married. Lupita died recently at the age of 106,” explains the author.

When Skal began his research, not only was there no internet, but there were hardly any sources to turn to. Horror movies didn’t seem to seriously interest anyone. He, like other monster kids, was educated in the light of the pioneering publication Famous Monsters of Filmland, by Forrest J. Ackerman, a magazine that suffered the attack of psychologist Frederick Wertham , who put the United States on red alert because children read horror stories and had homosexual models to imitate—as Wertham argued—like Wonder Woman or Superman. “When we were little they told us that these movies were bad for us, that we shouldn’t be reading those magazines, that they were going to fry our brains. If the teachers found you reading Famous Monsters of Filmand, they would confiscate it and throw it in the trash,” he says, laughing.

“Every major crisis sets identifiable patterns in motion to generate the terror that the public wants”

And yet he sees something of Wertham in today’s times, just as he finds echoes of McCarthy in Wertham. Asked about his next projects, he changes his expression and becomes worried: “I am working on a book about terror in politics. It’s called I Hear America Screaming, and it talks about everything that’s going on. It is not a joke. I approach it with some humor, but it’s not funny. Many Americans want to live in a horror movie. And it’s starting to happen all over the world. There are a lot of horror themes embedded in that. I’m going to write about all those nightmares we believe in...Pizzagate or QAnon could not exist without horror films.”

Skal does not smile when he talks about his country’s politics. He sees parallels between the present and a not-so-close past. “There is a very well-known book called From Caligari to Hitler, and it gives me the impression that we are embarking on that path again. When I started writing Monster Show I realized that in Germany in the 1920s, in the pre-Nazi era, people were attracted to those grotesque and terrifying characters like the Golem, Nosferatu, Caligari... Although they didn’t know why. It was like they had to process what was happening, but it was easier to put a mask on what was happening. I watched it pass decade after decade. During the Great Depression, in World War II, in the McCarthy era, in the sexual revolution, during the emergence of AIDS... Each great crisis sets identifiable patterns in motion to generate the terror that the public wants.

The pages of Monster Show are full of horrors, creatures, rituals, superstitions and evil men in the shadows “There are no new monsters. The archetypes are very strong. The mad scientist, the creature who returns from the grave. The man with two faces. And the freak. They are a catharsis,” he explains. It seems that the monster kid who read the Warren comics and watched the Universal films has never stopped inhabiting this smiling gentleman.

“When I was 10 years old, monsters comforted me, because they couldn’t die. They were like friends. Later, when I started researching the book, which I initially wanted to be just about monsters, I realized that all the things that had happened at that time, like the Cuban Missile Crisis or the Cold War, were out of my area of interest at the time. I would go to the front pages of the newspapers and from there straight to the culture and entertainment section,” he reflects. “I saw that, for example, the No. 1 song on the charts at the time of the missile crisis was The Monster Mash, a song about death sung by a crazy scientist. “Then I remembered that those headlines scared me a lot, and I realized that I had buried those memories.”

He does not conceal that he prefers the cinema and horror of yesteryear. “I get the impression that the public only gets impressed with murder, with sadism. I don’t like torture for torture’s sake. I like my monsters in black and white.” Before leaving, he talks about his relationship with his fans: “They are much more affectionate here than in the United States. There, when I go to festivals, I often notice that they are upset because I analyze the films. They feel like I’m taking all the fun out of horror movies. Most viewers don’t ask themselves why they like what they like.” Skal says goodbye and goes up to change for a screening of Melford’s Dracula at the Filmoteca Española cinemathèque in Madrid: “I want to go dressed in black.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.