The most wanted man in history, Waldo has gone into hiding again

A new edition of Martin Handford’s ‘Where’s Waldo?’ being published in Spain demonstrates the eternal appeal of a simple formula involving drawings, paper, and concentration

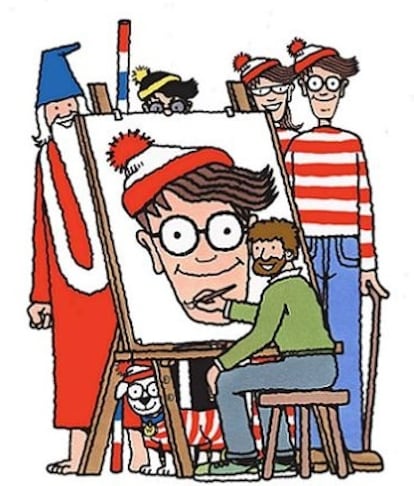

He is not a criminal (as far as we know). He hasn’t found out important secrets or seen things he shouldn’t have. And yet, for decades, he has become the most wanted man on the planet. Not a day goes by without someone hunting him down. Men and women, children and grandparents, from Albania to Zimbabwe. Everyone is looking for him. He does little to stand out, starting with his clothing: red and white striped sweater, beanie, and jeans. But despite his everyday appearance, he’s hiding a unique talent: wherever he goes, he ends up in a very crowded place. It’s clear that Waldo (known as Wally in the rest of the world) doesn’t quite understand sustainable tourism. Instead, he has demonstrated his mastery in a few matters: success, attractiveness, creativity. He hasn’t been able to go anywhere undisturbed for 37 years: it was 1986 when his creator, the artist Martin Handford, first drew him on the corner of a public square. Since then, millions of enthusiastic readers have entertained themselves by searching for him wherever he is: the beach, the stadium, Hollywood… Or prehistory, one of the settings for his new adventure, Where’s Waldo? The Search for the Lost Things.

It is, in reality, more of a return. B de Blok, its label in Spain, has now recovered this classic from the saga 11 years after its first triumphant release. The new edition has cutouts and extra materials. And a certainty, expressed by the literary editor Isabel Sbert: “Wally has managed to establish himself as an iconic, everlasting brand with a universal appeal. It would be difficult to find anyone who doesn’t recognize him. Young and old like the challenge of finding him, and it never goes out of style because it connects with something fundamental: our need for entertainment.”

The truth is that finding him in the middle of a castle siege on the first double-page spread still requires a pleasant mix of time and concentration. And even more so if you want to find Wenda, the wizard Whitebeard, Odlaw and the elusive dog Woof, whose tail is the only part of him that can ever be glimpsed. Or to the strangest episodes and characters that surround the protagonists. “With the challenge of searching for a bespectacled tourist, Handford tricks us into studying the minutiae of his scenes far more closely than perhaps we would otherwise. […] All of humanity is represented in Waldo’s world. Politics, economics, war, love, death, art, yes, even literature is offered up, discussed, lampooned and celebrated within the simple interactions of his million-strong cast,” cartoonist Lorenzo Etherington wrote in a column in The Guardian in 2016.

Waldo has appeared in seven books and has sold millions of copies in more than 80 countries and in 26 languages. He also made his creator a millionaire after Entertainment Rights group paid Handford about $2.9 million for the global rights to the brand in 2007. After all, it is a true empire, which has spun off animated series, video games, mugs, and t-shirts. And even the real world, where the competition for the most massive gathering of Waldos brings together thousands of costumed fans from time to time. There are places where they love him so much that, in an effort to feel closer to him, they have even wanted to call him by another name: Charlie, Ubaldo, Wally, Jura, or Willy, among others. The original, on the other hand, is because in English the word Wally refers to someone who says or does something clumsy or absurd.

In Spain, the phenomenon is intensifying, according to Sbert: “We have noticed exponential growth in recent years.” Among other explanations, the editor believes that the first generation that adored him today is encouraging their children to find Waldo. And, what’s more, the character also knows how to steal the fan’s gaze away from screens and cell phones to a place that is entirely paper-based. All with an apparently very simple formula. And that, beyond some folding pages and some cunning games, has barely changed in almost four decades.

Maybe one of the secrets is hidden right there. Handford’s art is no mystery, and nor is his attention to detail: each double page spread is said to require about eight weeks of work. “I start out with a list of about 20 gags that I want to put in a picture, but more come to me as I am working,” he stated in one of his very few interviews with The New York Times in 1990. He also said that he lived in a “very small” house, with the bed in the middle of the living room, and thousands of comics and toy soldiers. He also said that he got up at two in the afternoon and worked until six in the morning; and he defined himself as “not very successful.”

It’s impossible to ask him what he thinks now. Handford hides even more than Waldo: Sbert says that not even she has any contact with him, since everything is managed with the rights owners. A self-exile from the spotlight similar to that of Bill Watterson, although not going that far: the creator of Calvin and Hobbes concluded his most famous series and has never wanted it to appear in formats other than a cartoon in a paper.

“Martin Handford is a very private man. And focused exclusively on his work,” noted Mike Heap, the executive director of Entertainment Rights, when the company acquired his work. The rest has been silence, drawings and some biographical information, perhaps mixed with the legend. It’s said he listens to the Bee Gees and The Clash. A lonely child, he was raised by his divorced mother, and from the age of five he became fond of designing stylized versions of the action sequences he had seen in films. Handford worked at an insurance company to pay his way through art school until David Bennett, then editor of Walker Books, approached him with the possibility of working on an illustrated book with crowded scenes, in the style of Frenchman Philippe Dupasquier. Thus began Wally’s infinite paradox: the more he hides, the more they search for him. Such is the fate of myths.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.