‘Cut the Crap’: The Clash’s fiasco of a swansong

The last album by the British band was a huge flop. Over 30 years later, it has been remixed by a fan and is circulating on social media under the name ‘Mohawk Revenge’

In the discographies of all long-standing artists, there is usually one ugly duckling, a release that makes no sense and is either the result of the record company’s greed, or a testament to a time when the artist lost his or her way.

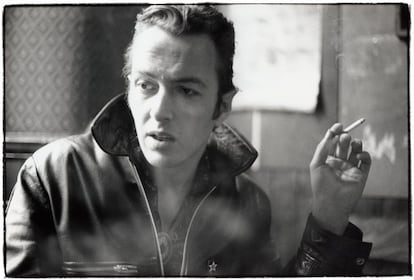

Cut The Crap (1985), which turned out to be The Clash’s final album, belongs to that last category. Amazingly, the band was fresh off its commercial peak with Combat Rock (1982), and its members were being courted by admirers like Martin Scorsese. But instead of marking time by, say, making a soundtrack, the leader decided to break the toy: Joe Strummer ditched his right-hand man, Mick Jones, and fired drummer Topper Headon, who was affected by his addiction to heroin (although he had just written one of The Clash’s biggest hits, Rock The Casbah).

Strummer kept the bassist, Paul Simonon, a cool guy but with few musical contributions to make. He completed the band with little-known musicians and they all ran to a recording studio in Germany, possibly to tune out the public outburst of criticism.

In theory, it could have worked: The Clash was going back to its origins, reinventing itself with the zeal of young disciples. But it didn’t work out. In the middle of it all was their manager, Bernie Rhodes, an egomaniac who decided that the future of music lay in punk anthems sung in choral style and embellished with elements of techno pop and dance music. It was simply horrible, and what’s more, Strummer’s voice was drowned out by the jumbled sound. To make matters worse, Rhodes concealed his ghastly production work behind a Hispanic pseudonym, José Unidos, which suggested that the real person in charge of this abomination was Strummer.

At some point, Strummer understood the true dimensions of the screw-up. He sought out Mick Jones to put The Clash back together, but his old partner was already busy with his next project, Big Audio Dynamite. An attempt to give the new Clash members some added experience through a clandestine tour of unplugged concerts inside bars and on the streets evidenced that the new project made no sense. Joe ended up fleeing to his beloved Granada in southern Spain, where he spent his time trying to locate the remains of the poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, killed and buried in a mass grave in 1936 at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.

This is how The Clash died. There was no comeback tour, no millionaire gigs at Coachella or other upscale festivals. The temptation surely was there: a few weeks before Strummer’s untimely death in 2002, he and Mick Jones played three Clash songs at a charity event.

Cut The Crap sank into disgrace. It is not usually included in complete editions or in the numerous compilations of songs by The Clash. The album is even ignored in documentaries.

Or so it was until recently. A few months ago, remixed versions of Cut The Crap songs began to leak through social networks, circulating under the heading Mohawk Revenge. The songs are the initiative of an admirer, Gerald Manns, who discovered software programs that allowed him to extract Joe Strummer’s vocals from the musical morass created by Rhodes. With infinite patience, he added bass, drums and guitars, basing himself on the live versions of those songs as they appeared on bootleg recordings. Mohawk Revenge could pass for the demo of Cut The Crap. It is a rarity, a whim, a posthumous sigh by one of the greatest blunders of 80s rock.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.