Forty years after a Roman villa was found in Spain, its owner remains unknown

Experts believe that the palatial complex was a significant center of power that received the Mediterranean’s best materials and ceramics

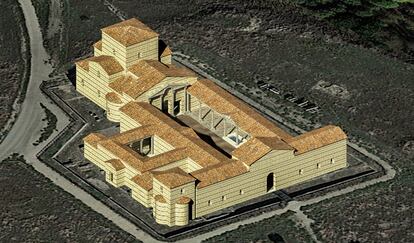

On July 23, 1983, Samuel Lopez, a resident of Carranque, a town in Toledo province, Spain, found some loose colored tesserae, or mosaic pieces, that a plow had pulled up on the outskirts of town. He began to scratch the ground with a stick and, only ten centimeters deep, he found the spectacular mosaic of The Metamorphosis, one of the 22 that covered the floors of the Carranque villa, which was built around 400 A.D.; 19 of its mosaics have been preserved. This monumental complex, owned by a great Roman lord or dominus, consisted of a country house, the Maternus House (which occupied about 1,200 square meters, complete with a porch, towers, garden courtyard and reception rooms), a torcularium (where oil and wine were made), a funerary building (where the owner and his family were buried) and a representation building measuring 2,000 square meters in size, which the most recent research identifies as a palatial building.

As indicated by the inscription found on one of the mosaics, we know that the owner’s name was Maternus. “From the workshop of Ma..., painted by Hirinius. May you happily enjoy this cubicle [bedroom], Maternus,” reads the mosaic that was on the door of the room. According to some experts, such as Dimas Fernández Galiano, the first archaeologist who excavated the site (1986-2003), that referred to Maternus Cinegio, a powerful consul appointed by Theodosius in 388, who died in Constantinople and whose wife Acantia took his body to Hispania. But most specialists, including Javier Arce (of the Spanish National Research Council and a professor at the University of Lille until his retirement), say that there is no evidence of that beyond finding the name Maternus on the mosaic. It was a common nickname at that time, the academic explains; thus, he says it is a leap to identify the owner as the consul. To avoid controversy, the site’s official website mentions only Maternus, without a nomen (which indicated the clan from which the person came) or cognomen (the person’s family). The owner of the villa lacks a surname.

The site, the official name of which is Santa María de Abajo de Carranque, was a center of agricultural production on the banks of the Guadarrama River and Via 24—an important road that connected the two plateaus—in the High Imperial Roman period (1st-2nd centuries A.D.), and it had significant wealth and monumentality in the Late Roman period, but it was also a center of power in a large territory. The existence of great buildings from the 4th and 5th centuries A.D., as well as the great quality, variety and quantity of the materials used in the decoration of the palatial building, attest to that fact. In recent years, they have become priority objects of study for a National University of Distance Education (UNED) research team, confirming that it is one of the most outstanding Marmora—ornamental marble ensembles—in the Western Mediterranean. After the middle of the 5th century, the complex went into decline, although it was reoccupied during both Visigothic and Muslim times. During the reign of Alfonso VII, the palatial building became the church of Santa María de Batres; in the 16th century, it was converted into a small rural hermitage, as appears in the Relaciones Topográficas de Felipe II [Topographical Relations of Philip II].

Carranque’s collection of mosaics –which were made by three different mosaic workshops—makes it one of the Iberian Peninsula’s most important. The mosaics cover 600 square meters and recreate characters from the Iliad, Neptune and Anemone, Diana and Actaeon, Hilas and the Nymphs, Pyramus and Thisbe, Minerva and Hercules.

Open to the public and managed by the Castilla-La Mancha regional government, the site shows the palatial building, where the dominus received his clients, guests and friends. It was built in granite, limestone and brick (opus mixtum walls with stone and laterite) with marble columns brought from Turkey, Tunisia and Greece; brick domes, some of which are covered with mosaics made of gold leaf tesserae; and walls and floors decorated with over 39 varieties of marble from the Mediterranean’s main quarries, used to create opus sectile compositions (marble cut into geometric motifs). And that doesn’t include what experts describe as “truly exceptional” tableware and furniture, such as vessels and parts of a table made of Egyptian red porphyry (Antiquity’s most precious stone material, the quarries of which were imperial property). Nor does it include the cover of a sarcophagus with iconography related to the prophet Jonah, which was made of marble from Estremoz (Évora, Portugal) and is now on display in Toledo at the Museo de los Concilios [Museum of the Councils].

The Maternus House was equipped with all the comforts of the day. In addition to its luxurious mosaic decorations, the walls of the house were painted with architectural and floral motifs. The mausoleum was a small funerary building with a square floor plan and a semicircular apse at the head. Numerous fragments provide evidence of the marble sarcophagi that housed the remains of the owner and his family. To the south of the Maternus House is the torcularium, the villa’s productive area, where, according to the most recent research, oil and wine were produced. Roman villas were actually enormous agricultural complexes in which the owner, his large family and workers lived. For the time being, the servants’ quarters, stables, barns, workshops and possibly a bathhouse have not been excavated yet.

Most of the ruins that can be visited today correspond to a group of buildings from the Theodosian period. Theodosius I the Great (347-395) was the last great Roman emperor; after him, the Empire was divided between the West and the East.

Samuel Lopez, who discovered the villa, complains about the lack of recent archaeological excavations. The latest ones occurred in 2016; prior to that, excavation work was done between 2005 and 2011, led by Carranque’s scientific director and UNED professor of Archaeology, Virginia García-Entero, who has also conducted a large survey of the site’s surroundings. “I found a wall about 20 meters long and about 80 centimeters thick, and I have asked to investigate several times, but my efforts have not been successful. It must be from a large building,” she says. Lopez also notes that the site started to receive 70,000 annual visits, mainly from schoolchildren and young people, but after the COVID-19 pandemic it never recovered those numbers, and now it is closed on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays. It does not make any sense.”

García-Entero explains that the research is currently focused on analyzing the voluminous materials recovered during the first phase of excavation (1985 and 2003) that have gone unstudied. “The laboratory work is extremely important, fundamental. Currently, while waiting to resume excavation work, we are focusing on the study of all the elements of material culture [ceramics, marbles, structures...] recovered, to which we apply a broad and rigorous protocol for analysis in collaboration with various Spanish and European institutions, including archaeobiological analysis, DNA, carbon-14, rock origin, composition of mortars and ceramic pastes and organic residues. Thus, the analyzed materials tell us that Carranque was a very important center of power at the end of the 4th century and beginning of the 5th century A.D., which received the Empire’s best ceramics, marbles, ivories and oils. [It was a] very special place, the best of the best.” The owner, however, remains unknown.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.