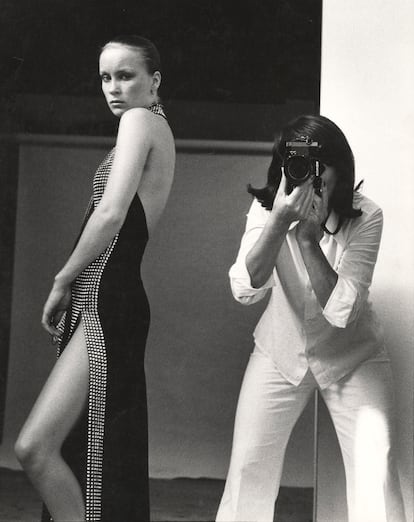

Alice Springs, the photographer who turned celebrities into humans

An exhibition in Berlin celebrates a unique photographic talent who almost always lived in the shadow of her famous husband, Helmut Newton

Overshadowed by the formidable media presence of her husband, the erotomaniac Helmut Newton, that controversial totem of 20th-century photography, the figure of June Newton (who used the pseudonym Alice Springs for her photographic work) has remained in the background for too long. On the occasion of the centennial of his birth, the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin does justice to her career with a substantial retrospective on display until January 21, 2024, which includes nearly 250 images, many unpublished.

June Browne (Melbourne, 1923-Monte Carlo, 2021) felt the calling to become an actress from a young age. In fact, it was in a theater that she met Helmut Newton, a German photographer from a Jewish family that emigrated to Australia when the Nazi barbarism began. One afternoon in 1946, he attended a play where she was acting and fell in love instantly. For weeks he waited for her at the dressing room door until they started dating. They were married in 1948 (she then took her husband’s last name) and did not separate until his death in 2004.

In 1961 the couple lived in Paris, where his career was taking off and where she began her love affair with the camera quite by chance. “One morning in 1970, Helmut couldn’t get out of bed because of the flu,” June recalled in Mrs. Newton, her 2004 autobiography. “He had a shoot in Place Vendôme for an advertisement for Gitanes cigarettes. I had already worked as his assistant, so I asked him how to read the light meter and how to charge the camera, I showed up there, and I did the job myself. When the customer’s check arrived, I knew I was in business.” Shortly before getting her first assignment from Depêche Mode magazine, Browne went to dinner at actress Jean Seberg’s house. The American interpreter’s boyfriend took out a map of Australia and a pin and asked her to stick it on the map with her eyes closed. It fell in the city of Alice Springs, which since then became her alter ego for future sessions in Vanity Fair, Interview and Vogue, which are documented in the current exhibition.

There, her mastery of psychological portraits are also highlighted, such as those in Us and Them (1998), a photobook shared with Helmut that created a delicious visual game in which each one contrasted their images of a celebrity in different life stages. The result is a parade of the cultural jet set of recent decades: writers (William Burroughs, Christopher Isherwood), artists (Joseph Beuys, David Hockney), performers (Charlotte Rampling, Vittorio Gassman), filmmakers (Federico Fellini, Agnès Varda) and designers (Karl Lagerfeld, Vivienne Westwood). All were immortalized in public spaces or in their homes and with natural light. “She was interested in the person behind the mask, in their soul,” explains Matthias Harder, curator of the exhibition and director of the foundation. “She was an artist in her own right who, especially in the genre of portraiture, was at least on a par with her husband.” Harder, who worked with her since the institution opened in 2004 (Browne was president until her death), remembers her as an astute, fun, generous but demanding woman. “She had a deep respect for almost everyone, but she was also not afraid of anyone.”

In addition to her better known facets (advertising, fashion or nudes), the retrospective highlights her series Melrose Avenue from 1984, which shows her eye for street photography, capturing musical subcultures in that artery of Los Angeles, home of punks, skaters and rockers. As a voyeur nod, the exhibition recreates the apartment in Monaco where the couple lived and where they both managed their archives, now in the possession of the Foundation. “We’ve made some cool discoveries,” Harder confesses. “But it will take years to process all that material. Because Alice Springs created an autonomous body of work that is yet to be discovered.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.