The debate about Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic nose in the film ‘Maestro’

To play iconic composer Leonard Bernstein in his next film, the actor-director wears a fake nose that has become the subject of criticism. However, one of the main Jewish groups in the US has now come to Cooper’s defense

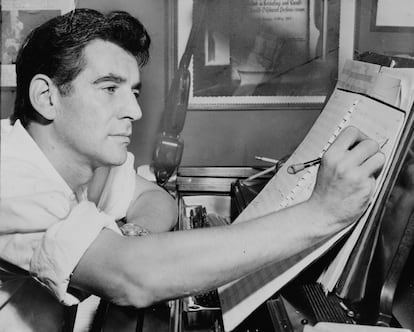

Pianist, composer, author, conductor, creator of the West Side Story melodies... Leonard Bernstein was all of that and much more. Such was his talent and the size of his body of work that now, almost 25 years after his death, Bradley Cooper has decided to bring his life to the screen. He has produced, directed, written and starred in a biopic, Maestro, which will premiere at various film festivals in September of this year. It will hit movie theaters in November and, by December, it will be available on Netflix.

Just a few days ago — after months of expectation — the first trailer for the film was released. Its duration of just over a minute has caused a flurry of criticism. This is because beyond Leonard Bernstein, played by Bradley Cooper, and his wife, Felicia Montealegre, played by Carey Mulligan, the protagonist of the footage has a surprising guest: Bernstein’s nose.

Born in Massachusetts to Ukrainian immigrants, Leonard Bernstein was Jewish. And, in the trailer for Maestro, his heritage is made clear via his features. As the creator of the film, Cooper — a gentile of Irish and Italian descent — has decided to give his character the composer’s characteristic nose. It’s slightly wider and larger than his own, made possible with a prosthesis. This has unleashed discomfort and criticism in some sectors.

For example, Daniel Fienberg — one of the film critics for The Hollywood Reporter — has described the prosthesis as “problematic” on Twitter. The debate over a nose has filled newspaper pages and hours of television debate on American talk shows. As a result of this outcry, several major Jewish organizations have come to Cooper’s defense.

Before these groups made statements, Bernstein’s relatives spoke up — they also supported Cooper’s creative decision: “It breaks our hearts to see how [Bradley Cooper’s] efforts are misrepresented. It happens to be true that Leonard Bernstein had a nice, big nose. Bradley chose to use makeup to amplify his resemblance, and we’re perfectly fine with that. We’re also certain that our dad would have been fine with it as well,” affirmed Jamie, Alexander and Nina Bernstein, who have explained that the actor and director included them “in all steps” of the creation of the film. “Strident complaints about this issue strike us, above all, as disingenuous attempts to bring a successful person down a notch — a practice we observed perpetrated all too often on our father.”

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) — a powerful American Jewish association, active for more than a century — released a brief statement to Variety regarding the issue: “Throughout history, Jews have often been portrayed in antisemitic films and in propaganda with large, hooked noses. This film — which is a portrait of legendary director Leonard Bernstein — does none of that.” In other words, the ADL supports the characterization of Bernstein in this way.

The nose, of course, goes beyond the nose itself. It’s about the representation of Jewish culture on the one hand, but also about actors and actresses who take on roles that don’t match their identities. British actress and activist Tracy-Ann Obermann — a Jewish woman — criticized Cooper on her social media (she has since deleted the post), writing that the fact that the actor put on a prosthetic nose was “equivalent to [someone] painting their face Black or yellow,” referring to practices that were carried out for decades to portray characters of African or Asian descent. “If Bradley Cooper can’t [do the role] with his acting alone, then don’t cast him — get a Jewish actor,” she said.

Obermann perhaps didn’t take into account that Cooper — as the writer, producer and director of Maestro — casted himself. However, she did refer to the fact that, a decade ago, when Cooper acted in The Elephant Man on Broadway, he didn’t wear a prosthesis.

This line of criticism has been directed at other actors in recent months. Cillian Murphy — Irish and Catholic — has been criticized for getting into the skin of nuclear physicist Robert Oppenheimer, a Jew, in the film of the same name. A commentator from The Jewish Chronicle wrote: “This may be because there is, from some of our storytellers presently, a fatigue, I think, a boredom, with Jews, and the strange incessant way that Western history has, often to their misfortune, placed them at the center of itself. This boredom is what leads to Jewish erasure, and that erasure is doubled down upon by the complacent casting of non-Jews as these great and complex Jewish figures of history.” Criticism has also intensified because the former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir has been played by the non-Jewish British actress Helen Mirren in the recent biopic Golda.

The issue of who gets to play what role is a long-standing one. Back in 2015, there were dissenting voices because Eddie Redmayne played the role of the transsexual Lili Elbe in The Danish Girl. In 2016, Scarlett Johansson was heavily-criticized for portraying a Japanese character in the adaptation of The Ghost in the Shell manga. In 2018, when she was signed to play a trans character in the film Rub & Tug, the outrage was so strong that she ended up rejecting the role. Two years later, Halle Berry also decided to say no to another film, in which she would have played a trans: “I understand that I shouldn’t have considered that character and that the transgender community should undeniably have the opportunity to tell their own stories,” she stated.

Last year, in an interview with The New York Times, Tom Hanks said that, today, he wouldn’t play the role of the homosexual AIDS patient Andrew Beckett, whom he portrayed in the 1993 film Philadelphia — a performance that won him his first Oscar.

Questions of race, gender and even nationality have long been on the table in the world of film. However, the question of religion was not. Until now. A nose has appeared on the scene to change the conversation.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.