New York’s MoMA takes off the colonial lenses

The ‘Chosen Memories’ exhibition, featuring donations from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros collection, uses the work of 39 Latin American artists to question the way this region’s history has been narrated to date

Regina José Galindo had eight pieces of pure gold extracted from the mines of her country, Guatemala, embedded in her teeth by a dentist. These expensive fillings were subsequently taken out by another odontologist in Berlin. The pieces that were removed from her mouth have since become small sculptures on display at the MoMA in New York and they play a part in the social debate in which museums have been embroiled for several years - decolonization.

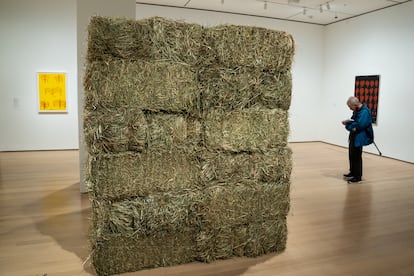

Chosen Memories, the exhibition that presents more than 60 works donated by the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection (which has invited this newspaper to see the display) to the museum over the past 25 years, carries no nostalgia or direct political criticism. “It’s not a debate that this collection touches on, but I believe that many of the works on display do so in a subtle way,” says Inés Katzenstein, curator and director of Latin American art at the New York museum.

The piece Saqueo, by the Guatemalan artist, denounces “the violence of the extractive economies” in its title. In other words, how excessive and indiscriminate mining in Guatemala has evolved into a new colonialism, the present-day form of the resource plundering of Latin American countries. “We are eternally despoiled people, but we are also resilient,” writes Regina José Galindo.

!['Tulúm, after Catherwood [The Castle]', by Leandro Katz,](https://imagenes.elpais.com/resizer/v2/JTJ3PCUJVFCPDCOTO2ZM6K3H5A.jpg?auth=3606062fba4316c2b6c43ed113d205527d626bf48907a1ee91d08935b3402283&width=414)

Her work resonates with that of 38 other Latin American artists who might not convey their messages as directly, but “imagine reparative paths” to portray their worlds. Such is the case of the landscapes from Colombia’s José Alejandro Restrepo and the lithographs by Argentina’s Leandro Katz. Their creations present a clear critical vision of how the European perspective has been imposed on Latin American territories and bodies for centuries. In Chosen Memories the colonial perspective no longer applies.

“Many artworks can be political when they provoke thought, and not necessarily when they define themselves as high-impact political art”, explains the curator, who believes that the debate on the decolonization of museums is more confined to those institutions that house archaeological pieces, and less so to contemporary art museums such as MoMA.

Perhaps one thing that the most modern artists, such as those featured in Chosen Memories with artwork from the end of the 20th century to the beginning of the 21st, have succeeded in doing is confirming that colonization was also artistic, with greater ease than the mesoamerican vestiges, for instance. Through means like video, sound installations, assemblage and photography they attempt to unravel this story. As the signs in the exhibition show, the colonial structures are being challenged. These structures still condition the ancestral cultures, even though centuries have passed since the independence of Latin American countries.

Only one interpretation

Although the Cisneros collection has always been closely associated with Latin American geometric abstraction, its founder quickly realized that “there was only one interpretation of Latin America,” says Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, the collection’s former director and chief curator, now an advisor to Cisneros, one of the world’s largest private art collectors. “For this reason, she began to search for indigenous works, including Afro-American artwork, something that has become increasingly important in the United States.” It was not very hard to find these pieces. History has marginalized these artists, but Cisneros and her husband, Gustavo, have spent years trying to learn what Latin American creators are doing. “She is a true, hands-on collector, she wants to know the artists, to see how they work, she is guided by their interests. Her husband is very familiar with the history of Latin America, how these countries were constituted. It was not difficult for them to find them.”

The art specialist believes that at the present moment “an intentional and politicized interpretation is given to these questions, but in some way they have been in the collection for a long time. That reflection on history and identity predates this specific moment.”

Many of these pieces have belonged to Cisneros’ collection for more than 15 years. She always strived to deconstruct “a paradigm of Latin America, which was Mexican muralism, Frida Kahlo or magical realism,” continues Pérez-Barreiro. Over a hundred pieces were donated by the collector to MoMA in 2016 and were not intended to be classified as a “Latin American wing”, an isolated section, but to be integrated into the museum’s narrative as part of the History of Art.

Katzenstein, the third in command of Latin American art at this museum since the 1990s, has approached this challenge in two ways. On the one hand, she manages 5,000 pieces by artists from this region, but not as an independent department. She ensures that areas such as that of the drawing or sculpture sections of the museum consider these pieces when rearranging the rooms of the permanent collection, which is constantly changing.

In addition, in the three decades that MoMA has had a director of Latin American art, efforts have been focused on monographic exhibitions. Now, under Katzenstein’s leadership, it goes one step further with this collaborative and thematic exhibition. Although those in charge do not want it to be seen as part of the current debate on the decolonization of museums, they do feel that “history is a living organism, in permanent interpretation and reevaluation”, according to the Brazilian photographer Rosângela Rennó.

Chosen Memories, April 30-September 9 at MoMA.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.