The road to the Holocaust: Racism as an integral part of European culture

George L. Mosse’s book ‘Toward the Final Solution’ explains the cultural foundations that enabled anti-Semitism and facilitated Nazi mass murder

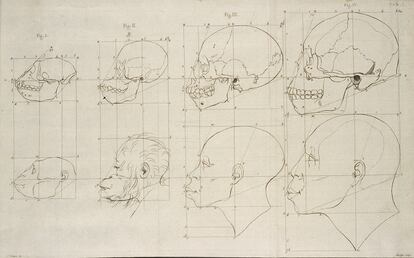

In the late 18th century, Dutch anthropologist Petrus Camper used what he considered a “scientific method” of cranial comparisons and facial measurements to study the differences between monkey skulls and the craniums of Black, Asian and European people. He measured the angle of a line drawn between the upper lip and the forehead, and a horizontal line across the face. He noted the different angles of the various heads and established the “ideal type of beauty” exalted by the ancient Greeks and documented by archaeologist and art historian, Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Naturally, the ideal type belonged to a white person, conclusively proving the superior race. It was also important for this ideal type to remain unsullied and not mix with other races. Racism was now supported by scientific research.

Historian George L. Mosse’s book, Towards the Final Solution, traces the history of racism from its modern origins to the Holocaust. First published in 1978 and recently reissued, the compilation of essays by Mosse includes an introduction by historian Christopher Browning, author of a classic book on the Einsatzgruppen paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany.

In his introduction, Browning writes: “Racism substituted myth for reality; and the world that it created, with its stereotypes, virtues, and vices, was a fairytale world, which dangled a utopia before the eyes of those who longed for a way out of the confusion of modernity and the rush of time.” The problem, of course, was that this myth led to an unfathomable bloodbath. Mosse sought to reconstruct the cultural background behind that catastrophe. The story of racism is not about “an aberration of European thought or scattered moments of madness, but an integral part of the European experience,” writes Browning.

George Mosse was born in Berlin (1918) and died at 81 in Madison, Wisconsin, in the United States. One of the greatest 20th century historians, Mosse was a homosexual from a wealthy and influential German Jewish family. This double marginalization shaped the course and interests of his whole life. His family fled Germany in 1933 when the Nazis took power and Mosse was sent to study at the University of Cambridge in England. In the 1960s, he emigrated to the U.S. and began teaching at the University of Wisconsin, a notably progressive university. He connected with the student movement of the 1960s, became interested in Nazi culture and ideology, and wrote one of his first significant essays on the intellectual origins of the Third Reich. Mosse sought to shed light on the ideas that permeated and set the course of a dark era in human history.

In The Nationalization of the Masses, he showed how certain ideals spread throughout German society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Wincklemann’s fascination with the Greek world and its customs, gymnasiums, choirs, hiking clubs and more. These rituals and collective memories developed into an exalted German nationalism. Hitler found that much of his work had already been done, and he only had to escalate the differences between insiders and outsiders to delirious heights. People like the Jews, who don’t belong to our tribe, should be exterminated. Although Mosse abhorred nationalism, he paradoxically drifted in that direction and ultimately became an avowed Zionist.

“Outward appearances represent inner grace,” Mosse observed as he studied the intellectual foundations of racism. It was only a matter of finding a very simple characteristic that would clearly separate people. By the 1850s, racist thought lumped Jews together with Black and yellow people as inferior beings, and the shape of the nose assumed an important distinguishing role. In Toward the Final Solution, Mosse identifies 18th-century Europe as the cradle of racism. He reveals how both the Enlightenment, with its eagerness to classify various peoples and its exaltation of Greek beauty, and Pietistic Lutheranism, with its emphasis on living a holy Christian life, planted the seeds of what would eventually become a “scavenger ideology.”

Then, German philosopher Johann von Herder came along in the 18th century talking about the Volksgeist — the spirit of the people or the national character. Herder argued that history was not shaped by humans, but followed a divine plan. Darwin championed theories of natural selection and survival of the fittest. Neither one was racist, but their ideas contributed to a narrative that exalted the power and grace of a chosen people over the burdensome masses. Mosse describes the new debate that arose about which European peoples had a greater love of freedom.

It’s surprising to read in Mosse’s book about how racism not only spread throughout nationalist ideologies but also infected Christian and socialist views. Mosse notes that Alphonse Toussenel, Charles Fourier and Pierre Joseph Proudhon were all socialists who considered “the Jewish race… predatory, competitive, and without morality, and was therefore to be excluded from participation in a genuinely national and socialist community.” Racism mixed with strong doses of nationalism and anti-Semitism turned into the lethal poison that later enabled the Nazis to exterminate six million Jews. World War One set the stage. From then on, Mosse notes, “political participation was defined by a political liturgy in mass movements or in the streets, seeking security through national myths and symbols that left little or no room for those who were different.” Jews were inextricably linked with the excesses of the capitalist financial system and later associated with the counterrevolutionary Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution. When Hitler became chancellor on January 30, 1933, racism became the official policy of the German government and everyone knows about the horror that followed.

One of Mosse’s main themes was to show was how racism enabled people to exalt themselves over supposedly inferior beings, so when the time came, “all the architects of the Final Solution looked in the mirror of middle-class respectability and liked what they saw.” They could not see the orgy of blood, obscured by the shining brilliance of the Aryan race.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.