From Shakespeare to RuPaul: the fight between crossdressing and conservatives goes back a long way and offers scripted twists and turns

Part of a centuries-old tradition of Anglo-Saxon entertainment, the controversy stirred up by the American right around the subject of drag queens also falls into a long history of moral, puritanical and religious panic

“Drag has been around forever. Here, in America, even our founding fathers wore wigs!” Linda Simpson jokes, in an email interview with EL PAÍS. Simpson is a New York City-based drag performer, who’s been active on the scene since the 1980s. Her show, The Drag Explosion, uses photos and anecdotes to preserve the memory of wild nights, LGBTQ+ activism and the drag movement in New York over the last two decades. “There’s a huge acceptance of drag these days, thanks mainly to the success of the television show RuPaul’s Drag Race,” Simpson writes. “People everywhere are now familiar with an art form that is full of fun and creativity.”

However, not everyone in the country agrees with Simpson and her colleagues. The phenomenon of Drag Queen Story Hour — an activity consisting of drag performers reading children’s stories in schools and libraries — has become the latest battleground in America’s culture war. At least 32 laws have been introduced across the United States to ban drag performances near minors. Tennessee is the first of the 50 states to pass the legislation, which defines drag shows as “adult cabaret performances” and restricts these kinds of shows. They cannot be held less than 1,000 feet away from schools, parks, libraries and places of worship.

“I think that the laws against drag are part of a general attack against the LGBTQ+ collective,” says the drag queen. “The real goal [of these lawmakers] is to exercise control and distract us from bigger issues, like the lack of access to healthcare for all people and economic inequalities.”

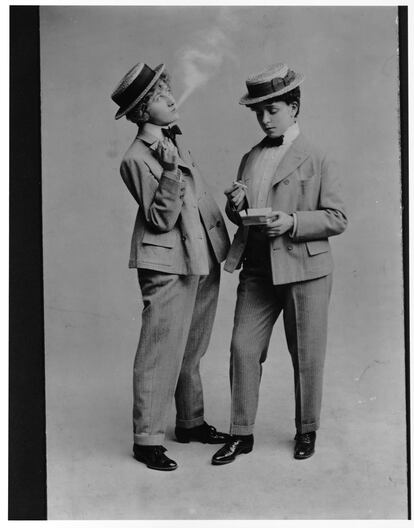

The moral panic over what the public should and should not see is quite old, although the scapegoats and definitions of “decency” have changed. Viewers of Shakespeare’s plays, for example, would have been horrified to see Juliet, Ophelia or Lady Macbeth being played by women and not by young crossdressers, as was customary in 16th-century England.

A little history of crossdressing

Daniel Smith, an associate professor of Theater History at Michigan State University, tells EL PAÍS by phone that, for much of the medieval period, “the idea of a woman showing herself in public life violated social and cultural conventions, so [a woman] on [a] stage was considered taboo. I suspect this also had to do with the association of theater with sex work. Brothels and the stage lived side by side in the same area of London, called The Liberties”.

The academic believes that double standards in the face of traditional gender roles were also a factor. Boys could receive an education — even if it was rudimentary — and be taken on as apprentices in theater companies. But girls could not. Several of Shakespeare’s plays used young men in female roles. “In Antony and Cleopatra, the Queen of Egypt laments that she will one day be played by a boy (”some squeaking Cleopatra boy”). And both As You Like It and Twelfth Night have boy actors, who play women who dress up as boys.”

Steven Mullaney, in his article Shakespeare and The Liberties, highlights how the theater generated tension between the civil and religious authorities of the time. The institutions were not only concerned that “the performers would change their appearance, transgress categories and imitate roles,” but also that theatergoers “would end up incorporating theatrical elements into their daily lives, threatening the social order.”

English theaters were closed indefinitely in 1642 by Puritan parliamentarians in the run-up to the English Civil War (1642-1651). “The prohibition that existed at that time is quite interesting. The argument used was, more or less, that these were times of political instability and that theater was a dangerous distraction,” Smith explains.

The beheading of Charles I of England in 1649 and Oliver Cromwell’s rise to power brought about a Puritan regime, in the literal sense of the word. During England’s only republican government to date, Cromwell and his devout Protestant backers banned taverns, Christmas celebrations, makeup, and colorful clothing, as well as theater.

Theaters reopened with the return of the monarchy in 1660, but the Puritan influence crossed the Atlantic and was embedded in the heart of the colonies that made up New England. An article in the academic publication Journal of the American Revolution highlights the contradiction that the United States has faced since its birth: the founders of the country defended freedoms and rights, while also vetoing stage performances, seeing them as being in the same category as gambling or dog fights. The prohibition lasted until 1789, but the concern about the influence of the arts on society — particularly on youth — lasts to this day.

Drag for the whole family

Smith sees a relationship between the aversion to having women on stage in Shakespeare’s era with the current controversy in the U.S. over drag shows. “The words ‘moral panic’ are a good way to describe it,” reflects the academic, who thinks it’s a response by American conservatives to the greater visibility of drag and the LGBTQ+ community in general. The Michigan State University professor believes that, at its core, the idea of Drag Queen Story Hour is quite innocent: “There’s a magical character in colorful clothes who reads a story to children and conservatives are against it, just because it exposes little ones to drag. I don’t see a problem with it.”

“Nobody makes a fuss about drag kings,” Smith adds, hinting at the counterpart of drag queens, which are women playing male roles. “The bulk of society probably doesn’t know what drag kings are because they don’t have the same media presence. All the focus, for better or worse, falls on the drag queens.”

Another point of comparison with the existing controversy in the United States is with pantomime or “panto” — one of the great popular traditions in the U.K. “You have, in British pantomime, a topsy-turvy idea of gender roles in a carnival show,” Smith says.

British pantomime is, in short, a traditional theatrical genre based on fairy tales (Peter Pan, Aladdin, etc.) that are interpreted in a mocking way with popular songs, current jokes or double-meanings. However, they’re suitable for the whole family, with lots of candy thrown to the children in the audience. These musical comedies are usually performed around Christmastime throughout the U.K., although they’re not well-known beyond the British Isles.

The academic explains that this theatrical genre was born from the Commedia dell’arte. Like its Italian ancestor, the panto usually has a stable cast adapted to different stories. Traditionally, a woman plays the role of the young and gallant hero, while a man plays the Dame — a loud and exaggerated woman who is usually a servant, a queen, or the mother of the protagonist.

“Historically, the traditions of crossdressing in the show have been more conservative currents that use mockery and misogyny to reaffirm gender roles,” Smith notes. “It transgresses by having a male actor play the role of a woman, but that role tends to be an undesirable woman who gets ridiculed.” For Smith, context and intention are everything. “The idea of a carnival can be, at a certain moment, an escape valve for social conventions, but [can also] end up reinforcing these norms.”

However, there are British actors who have expressed their affection for the panto. Actor Ian McKellen is a notable example: not only can he boast of having given life to Gandalf and Magneto on the big screen, he has also played Aladdin’s mother and Mother Goose on stage. In an interview to promote the latter, McKellen defined the role of panto in British society in the following terms: “We tend to be a people who don’t express our emotions in public. The panto is the maximum form of [release]... and not only with your colleagues, but with your parents, your grandparents, your brothers and sisters.”

What is evident is that, while the concept of crossdressing as entertainment has been a constant throughout the centuries, its use and meaning have changed radically. Smith points out that, for a long time, “it was assumed that these people were straight men who would put on a dress to make jokes about women.” Today, on the other hand, it is assumed that “a lot of [the people] who do drag are gay men or trans.”

Drag itself has also changed: the third season of the British adaptation of the television show RuPaul’s Drag Race featured Victoria Scone in 2021 — the first woman to participate in the successful franchise. The original U.S. version, meanwhile, had Gottmilk — a trans man — come in third place.

“We’ll see actions and reactions of all kinds as people redefine what gender is and how it manifests itself,” Smith predicts. “I think we’re experiencing a revolution when it comes to gender identity.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.