Can punks go to Mass? Transgressing is no longer what it used to be

In recent decades, questioning the established order has gained acceptance. According to the Spanish philosopher Alberto Santamaría, ‘When one punches, the fist ends up inside the body that it intends to destroy’

Roald Dahl’s work is often described as “transgressive.” Transgressive in the sense that he treated children as thinking beings, making them even more clever in the face of a world that is far from innocent.

The rewriting and re-release of these texts in their new English edition has provoked an overwhelming global reaction against what has been taken as an act of censorship. It has occurred with such surprising unanimity that it has made the publisher and Dahl’s heirs recoil.

One of the most common arguments in favor of the British author’s original texts has been, precisely, their transgressive nature. But is something really transgressive if it achieves unanimous consensus? Rather – as has been proven – the transgressor is the one censoring them.

Perhaps since the outbreak of countercultural movements in the mid-20th century – or even since the days of Romanticism, which saw rebellion as one of its fundamental values – the transgressor, the rebellious, or whatever goes against the “established order” has been gaining ground in society. Therefore, it’s entering a sort of paradox, as transgression has become the norm.

“The transgression comes from a historical moment, in which there were stable elements that one could face, that one could strike, whether it was the state, the traditional family or capitalism,” says the philosopher Alberto Santamaría.

“Today, it’s much more difficult: from the 1970s onwards, the processes are of integration. The vision of reality is no longer so stony, but more viscous. When one punches, the fist ends up inside the body that it intends to destroy.”

According to the author, neoliberal capitalism has understood that the field of culture is a perfectly valid place to install its hegemonic narrative. “The word transgression has lost its radical meaning,” he points out.

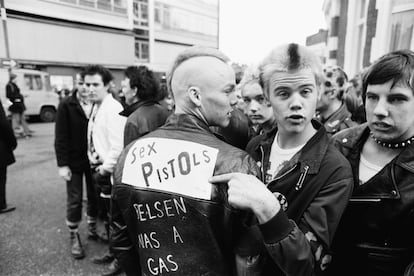

An example of this is the Sex Pistols: punk pioneers who scandalized British society in the late 1970s, because they used curse words on TV and called Queen Elizabeth II a fascist. Today, however, they are now part of the canon of popular music, inspiring collections put out by large fashion multinationals.

Another example: a punk group called Las Vulpes once sang a song on a major Spanish channel titled Me gusta ser una zorra (“I like being a slut”). This caused a huge scandal… but now, the tune is used to advertise cars and financial products.

“The capacity of the system to engulf rebellion – and even turn it into a business – is very high,” explains Carles Feixa, an anthropologist who specializes in youth culture at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona.

“This doesn’t mean that the spaces for transgression – whether progressive or regressive – disappear,” he continues. In fact, there are sociopolitical currents that try to turn the notion of transgression from progressive to reactionary via a strange game of mirrors, thus cloaking themselves in the irresistible charm of rebellion.

Traditionally, what is transgressive is that which goes against the social norms of the moment. It evades or contradicts them, and is therefore reprehensible and repulsive for the majority of society… or, at least, for those who govern it. The one who transgresses can be applauded by his close circle, by the breeding ground from which he springs, by those convinced and related, but, by definition, he cannot be celebrated and accepted by the majority.

It’s curious to see great writers, artists or musicians of a certain age, with careers behind them, complain that, today, they cannot be transgressed; because the grace of transgressing is, precisely, that “it cannot be done.” Today, though, nothing prevents it. The accepted transgression is no longer a transgression.

“Although complaints can be heard, the truth is that, in recent decades, we’ve greatly improved the issue of freedom of expression,” explains Juan Antonio Ríos, professor of Spanish Literature at the University of Alicante. “[During Spain’s democratic transition], transgression had a very clear meaning. Emerging from the dictatorship, it served to open spaces of freedom.”

During that stage, freedom of expression – which is now undervalued – was fought and conquered inch by inch in a climate of intolerance. Many times, the author points out, cultural products were validated for their transgressive nature… although the intrinsic quality was poor. But transgression sold.

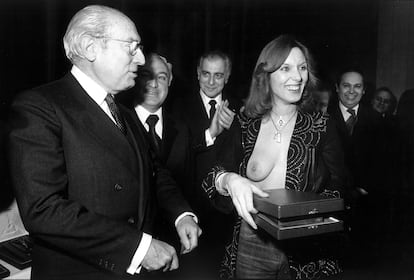

Transgressing certainly didn’t come cheap. Ríos recalls Susana Estrada, the famous Spanish actress who was prosecuted 14 times for public nudity, mainly for posing in pornographic magazines. She even ended up before the Supreme Court.

“For a while, she needed bodyguards, because she was constantly threatened.”

The bikini went through similar legal difficulties in the 1970s, especially when it was represented on magazine covers. While these incidents today may be laughable, they were very serious at the time.

Those who transgress face a wall of rejection and have to fight against it. No one transgresses when a boulevard of freedom opens up in front of them. Transgressors – if they succeed in their efforts – change society and, therefore, stop transgressing, because in the brand new world, what is theirs is no longer anathema. If they don’t succeed – if they fail in their transgressive adventure – they end up in oblivion, in hiding, or in jail, depending on the place, time and environment in which they operate.

Transgressing in the politics of a dictatorial country is not the same as rebellious performance in a liberal democracy. For example, the crime of public scandal disappeared from the Spanish Penal Code as recently as 1988, at the initiative of Nicolás Sartorius, then a member of the United Left. A case had caused enormous social commotion: a young man had been sentenced to prison for making out with his heterosexual partner and had taken his own life. Homosexual people, meanwhile, had been special victims of this law, as they had been charged under the Law on Social Danger. The Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court, in a 1982 ruling, ruled that homosexuality was an “obscene practice especially rejected by our culture and social environment.”

In recent times, transgression – already assimilated by the system – has become, more than a moral stance, a matter of style… and even of marketing. A not inconsiderable part of contemporary art has desired to be transgressive, as if that were just another style, without any risk or intention of political influence.

“The development of the art market has [made it so] that transgression has become its own element: thus, it’s diluted within the institutional. This is one of the problems of art, that the institution is far ahead of the transgression. This is a historical paradox,” points out Santamaría.

In general, transgressors in culture are now part of the canon, from Dadaism to the aforementioned punk, from the writers of the Beat Generation to the most radical filmmakers or the damned poets.

If the old transgressions are accepted, there are those who look for new ways forward in a society that has already seen it all. Sometimes the “normcore” – the normal and the current – has been claimed as the greatest rebellion against what it wants to provoke, merely for the sake of provoking. In many societies nowadays, a striptease in prime time isn’t considered to be a transgression, but a return to traditional values – such as the nuclear family, or religion – is.

Going further, ultra-conservative positions – such as racism or homophobia – have sometimes been claimed as transgressive. Just check out Twitter. The wet dream of some far-right cadres is to become a new kind of punk.

“The aim of ‘punk’ was merely destructive, but the extreme right uses the term in an empty, idealized way, and tries to reinstate what was stable. They seek not so much power, but control of certain elements of daily life. The idea of the traditional family, of the church or of going to Mass cannot be considered transgressive, but quite the opposite: [these notions] seek to recover what has been lost,” explains Santamaría.

Rebellion needs context. Francisco Franco was a rebel… as was Luke Skywalker. The difference is that the first faced a legitimate republic, while the second challenged a tyrannical empire. The space for transgression changes over time and sometimes goes from being based on the claim of freedoms and respect for all ways of living, to being in defense of what is reactionary or what is unacceptable.

Some say that, today, the only thing that can be truly transgressive is the defense of pedophilia, bestiality or murder (a trial, by the way, that could have been issued by the Marquis de Sade himself, giant of 18th-century transgression). The countercultural idea that rebellion and transgression are virtuous in and of themselves – which has given such good returns in the cultural field – is in trouble. Just like the well-trodden notion of freedom.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.