Vermeer’s light floods Amsterdam in Europe’s top art show of the season

For the first time ever, a collection of 28 of paintings by the Dutch master can be viewed together in a large exhibition at the Rijksmuseum

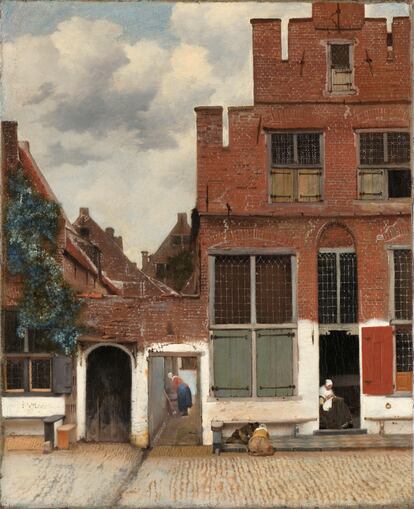

The View of Delft and The Little Street by the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), welcome visitors to the largest retrospective of the artist organized to date by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. These are the only two outdoor oil paintings by Vermeer and they act as the gateway to the private universe full of symbols of a maestro recognized in his time, then almost forgotten, only to be rescued from obscurity again in the 19th century by the French art critic, Théophile Thoré-Bürger.

The Rijksmuseum has managed to bring together 28 paintings from 14 museums and collections from seven countries on loan until June 4. This collection forms a formidable ensemble of domestic interiors bathed in light, and populated by enigmatic female figures and some of the men who visit them.

Simply titled Vermeer, the exhibition is the first to be exclusively devoted to the painter since the one organized between 1995 and 1996 by the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, and the Dutch gallery Mauritshuis, in The Hague. Having sold 200,000 tickets prior to opening on February 10, the Rijksmuseum has decided to extend its opening hours to 10 pm, Thursday through Saturday, in a bid to avoid crowds. “Not even Vermeer managed to see so many of his oil paintings together during his lifetime,” says Taco Dibbits, director of the Dutch museum, who strolls with obvious delight through the rooms of the Philips Wing of the museum. “Bringing them together was a once-in-a-lifetime thing. Now or never.”

As the museums that own works by the artist do not usually loan them out, it is considered a milestone that the Frick Collection in New York has sent the three Vermeers from its catalog: Lady with her Maidservant Holding a Letter, Girl Interrupted at her Music and Officer and Laughing Girl. Frick specialists have worked alongside those of the Rijksmuseum to be able to exhibit this trio of masterpieces, which joined the four Vermeers owned by the Dutch museum itself: the equally famous The Milkmaid, The Little Street, The Love Letter and Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. There followed three from the Mauritshuis Gallery: View of Delft and Diana and Her Companions, as well as the artist’s renowned Girl with a Pearl Earring. This last painting will return to The Hague in April. With 10 canvases in hand, the enthusiasm was contagious and other museums and private collections around Europe, the US and Japan ceded the remaining works.

Vermeer has been dubbed a mystery and called “the sphinx of Delft,” after his hometown. “Well, we are now closer to him than ever, even though he left no self-portraits,” says Pieter Roelofs, head of painting and sculpture for the exhibition. In the absence of an actual self-portrait, the smiling male figure looking out from The Procuress is considered a kind of representation. The canvas comes from the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, Germany, and features a red-cheeked young woman with a cup in her hand, receiving some coins for her services. “We don’t have his face, but, in a way, Veermer’s face is in every one of his paintings. In the use of color and light. In the perspective and his knowledge of optics. In the spaces that open and close, because he plays with the boundaries of what is ours and what is his,” adds Roelofs.

Distributed chronologically, the works are exhibited around a dozen rooms in such a way that the evolution of religious scenes painted between 1654 and 1655, such as Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, from the National Gallery of Scotland, and Saint Praxedes, from the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, can be observed, as well as the dominance of the female figure, ever-present in Vermeer’s work, dressed in either yellow or blue; with her hair up, or wearing a headdress or hat. Some are looking at the painter, such as A Lady Writing, from the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Others, such as the figure in The Milkmaid, keep their eyes on the task in hand.

As his work evolved, Vermeer became remarkably adept at layering his paints, which not only added texture but created a certain mood. “In Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, Vermeer first applied a layer of lapis lazuli to the jacket, then a first coat of pale blue to the wall,” says Ige Verslype, conservator and restorer of paintings at the Rijksmuseum. “Then a second coat of blue on the garment, then a final gray one to the wall. He left an open line on the outline of the garment, to diffuse the contours, something not done by other 17th-century artists. In addition, lapis lazuli appears in all the upper layers, from the face of the protagonist to the shadows and the map behind her, so there is a chromatic harmony.”

In The Milkmaid, the blue color is much more intense, particularly on a piece of cloth on the table and on the maid’s apron. “The mood of the woman in the Letter painting is serene, while this maid, who is alone and at work, draws our attention because of the vibrant ultramarine tone,” Verslype explains. The research undertaken to examine Vermeer’s developing style was also applied to The Little Street. “According to the latest research, the woman sitting on the threshold of the house, which belonged to his aunt, at first appeared on the right,” says Anna Krekeler, curator at the Rijksmuseum, who has participated in the technical analysis of the paintings. “The children playing in front were added later, and the red shutter, which now stands out, was added almost at the end. A window that was first painted ajar, ended up closed. Vermeer tells a story and only concludes it when he is satisfied.”

With an output of less than 60 paintings, Vermeer averaged about two canvases a year – a paltry output by 17th-century standards; Golden Age artist Rembrandt, for example, has a catalog of 340 works. But the mystery surrounding Vermeer derives in part from the lack of personal documents – there are no handwritten letters, as in the case of Van Gogh, who was a prolific letter writer.

It is known, however, that Johannes Vermeer was in contact with art since he was a child, because his father ran an inn in Delft and was also an art dealer. He learned his trade from a master, otherwise he would not have been able to become a member of the Guild of St. Luke in Delft. He himself came from a Protestant family, but he married a young Catholic girl, Catherine Bolnes, with whom he had 15 children. His mother-in-law, Maria Thins, was wealthy and opposed the marriage at first. According to Gregor Weber, chief curator of Fine Arts at the Rijksmuseum, the Jesuits showed the artist the use of the camera obscura, an optical instrument that was a precursor to photography. Weber believes it inspired Vermeer, but he did not use it in his works.

Supported by a Delft collector who bought around 20 paintings from him, the artist’s life came to a screeching halt in 1672 when the Franco-Dutch war broke out. Unable to sell paintings or support his family, he fell ill and died within a couple of days. According to the burial register of the Oude Kerk, or Old Church, in Delft, at least 14 coffin bearers carried his body, and the bell was rung once in his honor. It was an honorable end, financed by his mother-in-law. Subsequently, his wife Catherine had to declare bankruptcy, overwhelmed by the debts incurred by the painter. In the years that followed, Vermeer’s legacy was practically ignored. Now, however, he is mentioned in the same breath as Rembrandt and Van Gogh and is hailed for his depiction of the female figure, and his masterful use of perspective and color to evoke a predominantly meditative mood.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.