To rest is human, even if modern work culture brands it as shameful

Today, idleness is considered practically a sin, whereas being constantly busy and available online is celebrated. However, this has not always been the case

To many people, having lots of work, especially during times of inflation and economic turmoil, is a symbol of social status; In their eyes, stress is a measure of success. Rest, on the other hand, is regarded as nonsense and a waste of time. Sounds familiar?

In the midst of today’s rejection of idleness, French essayist Alain Corbin has published Histoire du repos (History of rest), an invitation to experience our relationship with fatigue and time in a different way. In his opinion, to say “I need to rest” is to formulate a wish, a feeling as certain as any basic need. Or perhaps not, because, he maintains, leisure has replaced rest. Leisure is taking up time and space. Meanwhile, more than 40 million people in the world (privileged, in their own way) left their jobs in the last year in a phenomenon dubbed the Great Resignation. Some people realized that they could find better ways to make a living – or not. What for?

In any case, we have to take into consideration the particularities of the times in which we live. While a couple of decades ago the cellphone had not infiltrated every aspect of our lives and the weekend was a time to disconnect (as well as midweek afternoons and evenings), today the term “disconnection” is relative and confusing. Much has been said about the harmful consequences of being permanently connected and available through our phones. Writing an email in the park equals a neglected child. It matters little that this is an era of permanent stress (and, as Mark Fisher ventured, of the “privatization of stress”), in which terms such as rest or relaxation have been erased from most people’s mental maps: a time of achieving goals and bonuses, sped up by the very technologies that were supposed to help us save time but have instead taken it away. Never mind the fact that in 2021 the scientific journal Environment International established long working hours as the biggest occupational risk factor, responsible for a third of work-related diseases. Or that another investigation by the World Health Organization and the International Labor Organization pointed out that every year, 750,000 people die of ischemic coronary disease and strokes due to their work timetables. Today, more people die from working too much than from malaria.

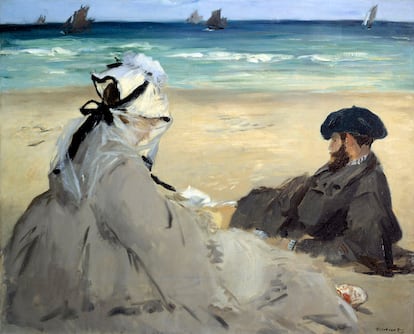

Facing the imperative of performance, Corbin’s goal is to understand the distance that stretches from the times when rest was seen as a matter of health – that is, a permanent state of happiness – to the great century of rest, which spans from the last third of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century, with the pleasant allegory of beaches, therapeutic rest in health clinics and paid vacations to relieve the fatigue of work. What changed between one scenario and the other? The Industrial Revolution.

In a conversation with French journalist Julie Clarini for L’Obs magazine, Corbin points out that the current obsession with the need to rest was born with the arrival of factories. Before that, rest was a part of work; the necessary short breaks were taken. Craftsmen and farmers managed their own time. Multiple periods of rest made the work-rest rotation subtle. Then, factories created timed work. This brings to mind David Rooney’s recent essay About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks, in which he talks about the importance of clock towers as tools of control that, at the same time, helped governments to condemn laziness. In the open air and in plain sight, these clocks urged people to avoid wasting time. Later, the pocket watch would appear, only to evolve into owner and supervisor, just like the smartphones of today. It is with excessive work that legal rest is established and new concepts such as “leisure,” “relaxation,” “concentration” or “disconnection” appear, as well as the sciences of the spirit of rest as a natural good.

To analyze today’s concept of rest we can turn to Google engineer Andrew Smart, who in his 2013 book Autopilot: The Art and Science of Doing Nothing, explains that certain brain networks become more active when we are not doing anything in particular. These moments are very important. It is similar to what happens with physical exercise, he emphasizes; if you walk for a long time, you need to stop and rest – and if that principle is not applied to the brain, then creativity and self-awareness become stifled. Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, founder of Strategy and Rest, a Silicon Valley-based consulting firm that helps companies implement four-day work weeks, published an article titled “How to Rest Well” in the Psyche Guides magazine, where he states: “Just as swimmers and Buddhist monks learn to use their breathing to maintain energy or calm their minds, busy people need to learn how to rest in ways that will help them recharge their mental and physical batteries, and get a burst of creative insight. That requires developing new daily practices, and thinking differently about rest.”

However, it is the always lucid Friedrich Nietzsche who comes off as more contemporary with the reflections he expressed in The Gay Science: “One thinks with a watch in hand [...] one lives like someone who might always ‘miss out on something,’” and “The true virtue today is doing something in less time than someone else.” “Rather do anything than nothing” has become a principle. Yes, Nietzsche saw it all coming, including the helplessness of man in the face of the abyss of existence and work, and the acceleration of time and the associated issues that modernity brought with it: immediacy and a never-ending technological connection.

To sum up: if the Industrial Revolution led to fewer rest periods and the aggravation of worker fatigue, among the privileged classes progress presented the possibility of a kind of rest that is closely related to the emptiness of time; to self-cultivation beyond the simple restoration of strength, that which today we call “personal time,” and which more closely resembles the original meaning of rest.

In The Use of Life (1895), Victorian author John Lubbock – a financial innovator and renowned archaeologist who used his wealth to save the ancient stone circle of Avebury in Wiltshire, England, and who, as a political reformer, led a campaign in favor of taking holidays – was very clear: “Rest is not idleness, and to lie sometimes on the grass under the trees on a summer’s day, listening to the murmur of water, or watching the clouds float across the blue sky, is by no means a waste of time.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.