What does a 160-year old wine taste like? A historic event at Marqués de Riscal has the answer

The Spanish winery, famous for its Frank Gehry architecture and recently ranked as the world’s second-best vineyard, opened bottles from 30 vintages dating all the way back to the 19th century

When Marqués de Riscal produced its first wine in 1862, Americans were immersed in the Civil War and French writer Victor Hugo had just published Les Misérables. These milestones provide some perspective on the historic event that took place last September, when the Spanish winery opened three of the only 16 remaining bottles from that vintage to kick off a unique tasting that spanned three centuries and showed that history can also be told through a glass of wine.

That wine from 1862 represents the oldest bottled Riojas in existence. With less than 10% of alcohol content (today the region’s reds range between 13% and 14.5%) and a more than decent color for its age, the liquid that poured out of the bottles at the tasting expressed earthy and tobacco notes, while excellent acidity served as the backbone to provide energy and persistence on the palate. It could have easily passed for a 40 or 50-year old red, except that it was 160 years old instead.

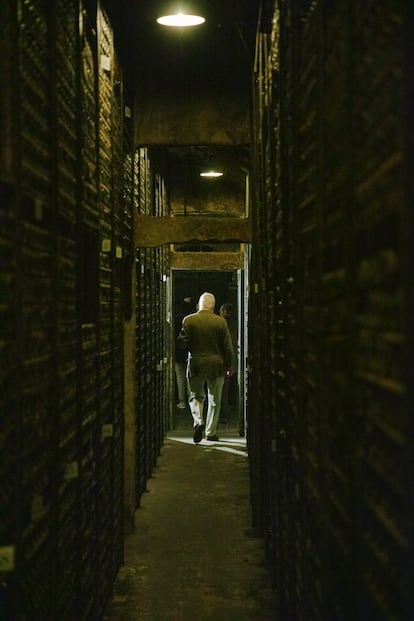

The collection that Marqués de Riscal carefully guards in its old wine cellar, the Botellería Histórica, is unique in the world, and it has miraculously remained intact through the ages in the silence and darkness of its underground cellars. The only changes to have taken place down here were to replace corks from specific bottles under the supervision of the Regulatory Council [which oversees adherence to the quality standards of the denominación de origen, similar to France’s appellation d’origine.]

The Marqués de Riscal winery, recently declared the second-best in the world, was born with the desire to produce fine wines that would age well. This was the vision of its founder, Guillermo Hurtado de Amézaga (1795-1878), the Marquis of Riscal, who had moved to Bordeaux in 1836 to avoid the political turmoil back home. The Spanish nobleman made the most of the vibrant commercial life this French city had to offer. His business prospered and he began to rub shoulders with members of a society that included the owners of some of the area’s most prestigious châteaux.

Very soon, he would have the opportunity to follow in their footsteps: he inherited a wine-producing property from his sister in Elciego, a municipality in northern Spain located in Álava province, within the current limits of what is now known as La Rioja Alavesa (because of its wine production and geographical proximity to the region of La Rioja, which the wines are named after). At the time, Rioja wines lacked the quality and prestige of their French counterparts, but the local administration teamed up with other producers with the common goal of raising the standard, and this gave birth to the Médoc Alavés. This initiative, named after the most famous area of Bordeaux and financed by the Álava Provincial Council, benefited from Hurtado de Amézaga’s contacts: they were able to hire Cadiche Pineau, an enologist at the then prestigious Château Lanessan, who showed up in La Rioja in the summer of 1862, in time to buy barrels, vats and all the necessary material for that first historic vintage.

One of the commandments of the Bordeaux philosophy was that wine had to be stabilized by aging it in oak barrels for at least two years, which created fixed assets and delayed profits. Although the wines were a success, a shortage of resources put an end to the Médoc Alavés. But the marquis carried on: he hired Pineau and continued to apply the French model. This included the sale of wine through Bordeaux merchants, the cultivation of French grape varieties alongside local ones, and the habit of hiring French enologists, a custom that continued until the mid-1950s.

If the 19th century was particularly turbulent at the political level, European vineyards also had to deal with plagues brought over from America. After mildew, the devastation created by phylloxera was a turning point in the world of winemaking. The only effective deterrent to the root-eating insect was to graft the European vines onto American rootstock, naturally immune to the pest’s attack.

Thus, nothing interfered with the flow of sap between the root and the aerial part of the plant in the vines that fed the 19th century red wines. Cultivation was restricted to the poorest soils, yields were low, and grape berries were small and concentrated. Only this can explain the fact that vintages such as 1870, 1876, 1886 or 1899 have amazingly preserved not only their color (1870 could pass for a 1970), but also their presence and volume on the palate, when the most common type of old Riojas are comprised of light and silky reds outlined by their acidity. In Riscal, in fact, the two styles coexist (there is the delicate and subtle expression of an 1871 or the evocative character of a ١٩٢٨), but it is the first one that gives the winery its differential touch.

The aromas of these centuries-old wines range from powdery notes to much more complex and even Baroque expressions: hints of brandy, dried fruit, sweet spices, coffee or chocolate. At the turn of the century, the 1909 and 1911 vintages, thinner and lighter, evidenced the lesser depth of the young vines and the slow reconstruction that followed the phylloxera crisis, although they retained a certain liveliness, particularly those from 1911. The wines from the 1920s were full of energy: with fruity notes in the 1922 vintage and mentholated, round and elegant ones in 1924. And 1935 made an impact due to its silkiness, rich nuances, herbal freshness and long finish.

Inside the documentary archive at Marqués de Riscal, there are old books, detailed descriptions of the different harvests and even characterizations of varieties developed by French engineers. “What there is no written record of is the percentages of varieties that they used in the wines,” notes Francisco Hurtado de Amézaga, the winery’s technical director for the last four decades and great-great-grandson of the founder. In the 19th century, it was common to mix grape varieties, including white and red ones, in the same vine. If the Tempranillo grape has always been present (Hurtado de Amézaga says that the best examples are exceptional), Graciano was the most difficult variety to bring back after phylloxera.

Of the grape varieties brought from France, Cabernet Sauvignon began to gain relevance starting in 1870, and it is the one that has had the greatest continuity to this day. Starting in the 1920s, but especially in the 1940s and 50s, the wines in which it was most present were internally labeled as Reserva Médoc or XR (Xtra Reserva). The paradigm of this style is the 1945 vintage, which produced a wide, exultant, very fine, serious wine with an endless finish that provides the characteristic notes of leaves and currant of this grape variety. It could pass for a great Bordeaux, and it is, without a doubt, one of the best reds that have ever been produced in Rioja and in Spain as a whole.

After a period that focused on wines with less aging capacity in the late 1960s, that indisputable wine from 1945 was the inspiration for what is considered the first modern Rioja. Barón de Chirel made his debut with a 1986 vintage that looked to France and benefited from the advice of renowned enologists such as Guy Guimberteau, Paul Pontallier or the current consultant, Valérie Lavigne.

More than a century and a half after its founding, Marqués de Riscal is perhaps best known for the Frank Gehry architecture that greets visitors, but its essence remains contained in each of the more than 140,000 bottles that sleep in its venerable cellars.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.