Emma Lazarus: The feminist poet who wrote the famous verses on the Statue of Liberty

A new book explores the short life of the New York writer who championed the waves of impoverished immigrants arriving on American shores

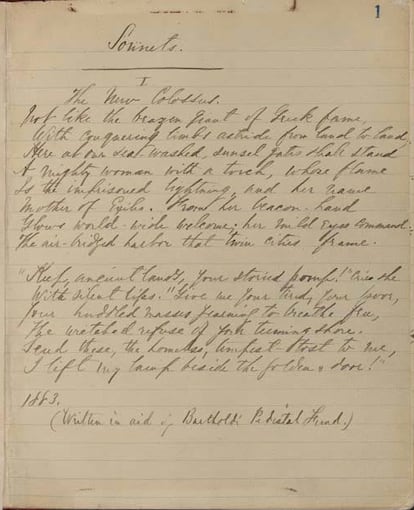

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.”

These words could be about everyone who has been uprooted by all the conflicts of the past, present and future. People who have been forced to leave their native countries in search of better lives. These verses from “The New Colossus” are inscribed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor, a welcoming message for those who came to a country forged by immigration more than a century ago. The sonnet that wasn’t penned by a founding father, a famous writer or any pivotal figure of the late 19th century. Its author was a Jewish woman, a feminist from a family with Sephardic roots (Jews who trace their lineage to the Iberian peninsula). Now her work has been published for the first time in Spanish, in a book that presents a selection of her poems and articles, along with a brief biography.

Emma Lazarus a los pies de la libertad (or Emma Lazarus at the Feet of Freedom), was written by Esther Bendahan and Israel Doncel, and published by Editorial Huso. It presents translations of the original English-language texts by Lawrence Schimel, and emphasizes the social consciousness and activism of Lazarus. She was born in 1849 into one of the elite families of New York, descendants of the first 23 Jews who arrived in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam in 1654, the settlement that would later become New York.

Lazarus and her six siblings all had private tutors, and Emma soon displayed a gift for languages. She learned French, Italian and German, and later translated the verses of German poet, Heinrich Heine. She also translated the writings of medieval Jewish philosophers into contemporary English, including works by Maimonides. Bendahan, who is the director of culture for Madrid’s Centro Sefarad-Israel, an organization dedicated to preserving the legacy of Sephardic culture, describes Lazarus as someone “who is part of Spanish history and a progenitor of contemporary Sephardic literature, even though she wrote in another language and place.” As an example, Bendahan cites Lazarus’ poem, The Exodus (August 3, 1942), about the Jewish expulsion from the Iberian peninsula by the Catholic Monarchs:

“The Spanish noon is a blaze of azure fire, and the dusty pilgrims crawl like an endless serpent along treeless plains… They leave behind, the grape, the olive, and the fig… the garden-cities of Andalusia and Aragon…”

Lazarus was a precocious writer and published her first book, Poems and Translations (1866), at the age of 17. It was praised in a New York Times review as “remarkable,” especially because it had been written by such a young lady during the three years prior to its publication. In 1874, Lazrus published her only novel, Alide: An Episode of Goethe’s Life. Two years later, she tried her hand at playwriting and published The Spagnoletto.

In 1882, Lazarus contributed an article to The Century, one of the most widely circulated magazines in the US at the time. However, in that same issue was an anti-Semitic piece by a Russian journalist, who called Jews “disgusting parasites.” Lazarus was so outraged that “from that moment on, she decided never to hide her Jewish identity,” said Israel Doncel, the Centro Sefarad-Israel’s director of communications. Later on that year, she published a collection of poems, Songs of a Semite.

Doncel describes the poems in Songs of a Semite as “highly intellectual and dense, almost like essays,” with themes like the discrimination and persecution of Jews in Europe. “Religious intolerance and racial antipathy are giving rise to an equally bitter and dangerous social hostility,” she wrote. Lazarus often struggled with her publishers. “I can’t do things on assignment. I am a poet, not a journalist,” she once said at a time when much of the press meekly answered to political and economic interests.

Her commitment to the Jewish people intensified when she saw the deplorable conditions and treatment of Russian immigrants. She wrote about homes with no running water, and the lack of schools for their children. Bendahan and Doncel says Lazarus was a trailblazing Zionist, years before journalist Theodor Herzl wrote The Jewish State (1896), considered one of the most important texts of modern Zionism. Lazarus had long called for an independent Jewish state.

Little is known about her private life. “We don’t know about any of her love stories or relationships… Her poetry is not romantic; it’s more in the vein of Mother Teresa’s social consciousness,” said Bendahan. A single woman with no children, Lazarus traveled to the United Kingdom and France in 1883, the year she wrote “The New Colossus” to help Joseph Pulitzer raise money for the construction of a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty, a gift from France. Lazarus composed the sonnet as a message of welcome to immigrant Jews entering New York Harbor. Bendahan highlights the poem’s verse about: “A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles,” and how Lazarus compares her with Europe, a land that expels its people: “Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land.”

When the pedestal was finally completed and the Statue of Liberty was unveiled in October 1886, the verses composed by Emma Lazarus three years earlier were all but forgotten. She was traveling in Europe at the time and was forced to return home early because of poor health. The 38-year-old Lazarus died on November 19, 1887. “No one knows for sure, but most likely it was from cancer,” said Doncel.

Emma Lazarus’s friend Georgina Schuyler, a writer and descendant of Alexander Hamilton, spearheaded the campaign to have “The New Colossus” added to the statue’s pedestal. On May 6, 1903, the plaque with her now-famous poem was unveiled. “While the unveiling of the statue was a well-publicized event, The New York Times only gave the plaque a few lines the next day. Her voice was drowned out because she was a woman and a Jew,” said Doncel, who hopes the book he authored with Bendahan will give Lazarus her proper due in Spain.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.