The new horror: Nothing is as scary as reality

Guillermo del Toro, Mariana Enríquez, Álex de la Iglesia and other leading figures in the genre explain what truly frightens the public now

What terrifies audiences and readers these days? In honor of Halloween, leading film and literary figures and experts in the horror genre unravel what causes screams, frights, goose bumps and anguish today. Following the Covid-19 pandemic and quarantine, terror stems from everyday life. When millions of people have died of a disease, Lovecraftian beasts become less frightening than an ungraspable illness that could kill one’s family.

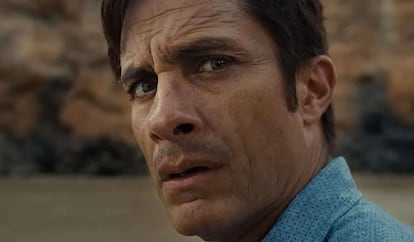

Last week, just in time for Halloween, Netflix released Mexican director Guillermo del Toro’s series The Cabinet of Curiosities. The show’s eight episodes delve into his terrifying worlds. The filmmaker – whose stop-motion animated movie, Pinocchio, is about to hit theaters – explains in an email what he believes to be most terrifying to audiences today: “The world has become a place full of fears that control us, that hover like dark clouds every day. We have never been closer to the end, so the horrors that work have to come alongside an identifiable reality. They have to be plausible and somehow more immediate.” Curiously, his series draws on Lovecraft’s more fantastic universe, and two of the episodes are adapted from the American author’s short stories: “Some old mechanisms still work in the storytelling but not as a primary driver of fear. They are two different things: the poetics of horror and the function of fear.”

Argentine author Mariana Enriquez, whose short stories and novels lead a generation of Latin American storytellers who have shattered the old canons of literary horror, concurs. Now promoting her novel Our Share of Night in the United Kingdom and El Otro Lado (The Other Side), a compilation of her journalistic work, in Spain, the writer observes that “clearly, horror has been changing since the 1970s, thanks to Stephen King, who brings [the horror genre] closer to the everyday. He was the one to bridge the gap and bring horror into society, [social] classes and politics. Carrie is a story about bullying, but it’s also about social class, religious fanaticism, adolescence and hazing, and women. The book is a step forward. It takes us from The Exorcist [1973], which has the relationship between a mother and a daughter entering adolescence as its backdrop, to Robert Eggers’s The Witch (2015), which is about a woman who ends up finding herself and her own desire. That’s a blend of reality and the supernatural that we’ve seen [everywhere] from the first season of True Crime to Samanta Schweblin’s novel Fever Dream, which combines eco-terror with a mother’s fear of her son transforming into something else: it’s panic about the future.”

In the year 2022, Enriquez says, “all these elements are intertwined in today’s horror and have the nuance of everyday panics: the fears of isolation, technology, sickness, losing touch with reality, living in a simulacrum, loss and the fleeting nature of existence. Horror stories are at a very high point right now; we also see it in videogames. Horror spills over into other genres; it’s no longer strictly regimented.”

Filmmaker Álex de la Iglesia, who directed Venicephrenia and El Cuarto Pasajero (The Fourth Passenger) and is currently working on the second season of his series 30 Coins, proclaims that “cinema has produced some real gems recently.” He ironically adds that “some even call it upscale terror.” De la Iglesia asserts that what scares us now is “the outside [world]. The media and the free-market model have combined to make it so that nobody wants to leave their house. You fear change, you only want to communicate by internet, you only want to shop online and… the outside is a savage world that you don’t want to go near. You are terrified that someone will enter your home. You see it in today’s films: there are many movies about moving and adapting to an unfamiliar place. Even the bathroom and the kitchen are scary; the only thing I can control is my own bed, and sometimes not even that.”

According to journalist and horror expert Desirée de Fez, the author of the book Reinas del Grito (Scream Queens) and creator of a podcast of the same name, “horror films have their finger on the pulse of current events, sometimes unconsciously on the part of their creators. If you look at post-Covid cinema, there have been a lot of films where the horror begins with isolation. And we can see two other things as a product of the pandemic situation: horror films about the destruction of the family or mental illness, like Smile, and those that draw on fears of old age, because we are afraid of not being able to take care of our elders, or that they will not take care of us. There are many films with old people who do bad things, such as X, The Elderly and The Grandmother.” De Fez argues that “there aren’t any new fears, but they change with the times.” She mentions filmmaker M. Night Shyamalan as someone whose work exemplifies these trends: “Last year, M. Night Shyamalan released Old, which is about old age, and [his movie] Knock at the Cabin, about an apocalypse told from [the perspective of] isolation, will come out next year.”

Antonio Torrubia of Barcelona’s Gigamesh bookstore, which specializes in horror and fantasy, is highly attuned to new trends in the horror genre. He agrees that literature has been influenced by Covid-19. “[For example, in] We Need to Do Something by Max Booth III, after receiving multiple tornado warnings on the phone, a family locks themselves in the bathroom until the threat passes. When they realize that they won’t be able to get out for a long time, claustrophobia, paranoia and fear take over the story, and increasingly strange events push the family’s relationships to the limit.” He explains two major aspects of current horror: “Along with these fears of everyday life, Lovecraft’s most cosmic horror is still alive, as confirmed by Del Toro’s series and Venus, Jaume Balagueró's film, which premieres in December.” What is the best-selling horror book right now? “Jay Kristoff’s Empire of the Vampire and works by Grady Hendrix. And I always recommend The Girl Next Door.”

In literature, “fears haven’t been exhausted, and neither have the [associated] metaphors, symbols, and myths,” explains Ecuadorian author Mónica Ojeda. Ojeda’s writing reveals her talent for illustrating and reflecting on the many types of violence in the world, especially against women. As Ojeda puts it: “If there’s anything that scares me, it’s violence and cruelty; that’s because I come from an extremely hostile city [Guayaquil], a place where you are afraid to take your body out onto the street. That kind of fear transforms you: it’s not something external; it’s a fear that gets inside you and makes you more selfish, more distrustful, more violent yourself as a response to the violence that’s inflicted on you. That’s why I ended up writing about the violence of intimacy. That’s the greatest horror…before you can stop it, you’ve become the monster yourself.”

With this year’s debut of her first feature film, Piggy, a slasher movie that is also a social commentary on bullying and fatphobia, Carlota Pereda has become an important voice in horror cinema. She is currently working on her second movie, La Ermita (The Hermitage). Pereda observes that “now, fears are more rooted in the present; they are more tangible. You have to stick to society’s fears, such as global warming. Diabolical threats must be linked to the family, even with savage characters like the one in Terrifier 2. That’s why found footage [films made with footage shot by others in the past and found by chance] succeeds, because we feel that it’s plausible. On the other hand, supernatural threats have to be even more beastly, because today everything is too little by comparison.”

Sergio G. Sánchez – the co-writer of The Orphanage and The End and director of Marrowbone, whose show The Girl in the Mirror recently premiered on Netflix – is a veteran of the horror genre. He points out that “there are few barometers as accurate about each era’s concerns as literature, cinema and horror shows. [The fact] that we are living at such a productive time for this genre… indicates that we’re living in a society plagued by fears. We have given technology permission to invade, control and monitor our lives. Since the pandemic, it’s been our fate to live in fear. We started to feel that the world we live in, which once seemed so solid and safe, is actually extremely fragile.”

Film and television screenwriter Gema R. Neira, the co-writer of Malasaña 32 and 13 Exorcismos [13 Exorcisms], echoes Sánchez’s point: “The fear you experience from an intrusion in your home or in your family…that is absolutely universal. Psychological terror, focused on the thing that attacks what you love the most, works. It may be that when you close the door, the monster doesn’t stay outside, but is actually waiting inside for you.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.