How Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia’s fearless founder, turned an outdoor clothing brand into a political phenomenon

The entrepreneur, now legendary for announcing that his company will donate all of its profits to saving the planet, makes products that appeal to seasoned mountain climbers and fashionistas alike

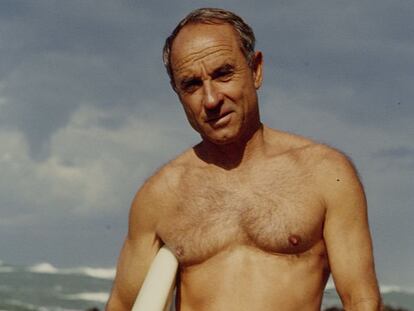

In 2018, Yvon Chouinard sat in an armchair on the stage of the Commonwealth Club of California. He wore an ochre jacket, light blue shirt, dark jeans, and ergonomic shoes. He looked more like a rural lumberjack than the founder of Patagonia, the best-regarded clothing brand in the United States in 2021 (according to an Axios Poll).

Chouinard is now a global legend following last Thursday’s announcement that his company will donate all of its profits (except what’s invested in the company itself) to a trust dedicated to saving the planet from the ravages of climate change. Five years ago, Chouinard told a large audience at a respected forum in the richest US state why he never planned to be an entrepreneur: “I started in the 1960s. And in the 1960s we all thought businessmen were creeps. We were part of the counterculture and we didn’t respect businessmen who, in fact, represented the enemy. But one day I woke up in the morning and realized that I was one of them, so I started reading a lot of business books and thinking about how I could create a business I wanted to be a part of. Not just me, but all my associates, because we were [all] ‘dirtbags.’” In the 1960s, “dirtbag” was the term used to refer to a very specific type of hippie: one who went deep into Yosemite National Park to live alone, climb El Capitan’s spectacular walls and spend the night outdoors stargazing.

Chouinard was such a “dirtbag” that when he was 15 years old he taught himself blacksmithing just so he could make his own climbing gear in a small workshop. In his homemade forge, he molded carabiners that he then sold to his friends, who were also passionate rock climbers. That planted the seed for a business that now, 40 years later, sells moderate- to high-priced organic cotton fleeces, windbreakers and T-shirts (a Patagonia fleece costs around $400, a parka is about $800). Experienced mountain climbers, Wall Street executives, fashion experts and influencers alike covet the brand’s garments. Indeed, the company’s humble logo - inspired by the silhouette of the legendary Mount Fitz Roy in Patagonia – has become such a status symbol that the brand has been nicknamed “Pradagonia.” How did Chouinard accomplish this?

In 1965, he and a friend founded Chouinard Equipment. By 1970, the company was already the United States’ leading supplier of climbing equipment. Back then, pitons were the company’s signature product. When they realized that the products were causing irreparable damage to the rocks and, more importantly, that they were not making much of a profit, they decided to go into the clothing business. They founded Patagonia in 1974 and established the headquarters in Ventura, California, a city inextricably linked with counterculture, the summer of love, and outdoor sports (especially surfing, another of Chouinard’s great passions).

The brand specialized in creating innovative materials to allow people to go to the mountains without being cold or needing to wear overly heavy clothing. Patagonia’s revolutionary idea was to democratize mountain climbers’ time-honored system of wearing layers. The company would manufacture much lighter/less bulky garments. The items were expensive to buy but for good reason: the products and fabrics were the most innovative ones available, and the company implemented a humane and employee-friendly policy in an industry where quasi-slavery was the norm. Moreover, paying a little more was worth it: Patagonia offered such high-quality clothing that one could wear the garments until, as Chouinard put it, one had to stop “as a matter of decency.” In a world defined by constant change, Patagonia’s founder chose consistency. To this day, Patagonia prides itself on its garment repair service, and the brand’s slogan remains “If it’s broke, fix it!” Of course, the company does cater to some of the market’s vicissitudes. In the 1980s, an era when neon reigned supreme, Chouinard wondered why mountain clothing had to be ochre, dull, and sad. His response explains how Patagonia became the first sports brand to pique the general public’s interest in outdoor clothing.

While that might tell us why the brand’s sales were so successful, it doesn’t differentiate Patagonia from other outdoor clothing companies like North Face (the company’s main competitor, although its owner, the late Douglas Tompkins – a legend in his own right –was one of Chouinard’s best friends). Nor does it help us understand how Patagonia became the most respected company in the United States. To appreciate the reasons for that, we must remember that in the early 1980s, Patagonia had already announced that it would allocate 1% of all its profits to environmental activists. In the 1990s, when “sustainability” was still a dirty word for most textile corporations, Patagonia commissioned an independent consulting firm to prepare a report on the environmental impact of the company’s primary fabrics; Chouinard learned that cotton caused the most damage to the ecosystem. “After several trips to the San Joaquin Valley, where we could smell the selenium ponds and see the lunar landscape of cotton fields, we asked a critical question: How could we continue to make products that laid waste to the Earth in this way?” he has recounted on many occasions. The company began to work exclusively with organic cotton growers and let everyone know about it. The brand’s unmistakable white T-shirts with the Patagonia logo became a symbol of something more.

But that was just the beginning of a decade in which Chouinard took a number of steps to demonstrate that his primary concern was his company’s environmental and social impact. For example, in 1996, Chouinard installed a solar panel system at the company’s largest distribution center in Reno, Nevada, making it energy self-sufficient. In 1998, then-US President Bill Clinton invited Chouinard to a government panel about ending sweatshop labor. That was how the Fair Labor Association – the organization that monitors textile companies around the world to ensure that workers are not exploited at any point in the production chain – was born.

Chouinard has always enjoyed good relationships with Democratic presidents. In 2015, President Barack Obama gave Patagonia an award in recognition of the company’s work-life balance policy (it has an on-site childcare center for employees’ children). The Clintons have long been unwitting walking advertisements for Patagonia products. Indeed, for over twenty years, Hillary has worn the same Patagonia fleece for her famous walks in the woods, even though, as Elle magazine noted last year, “Patagonia is the Bernie Sanders of fashion.”

If the entrepreneur has retained a certain aura of independence, that’s because he has always controlled his own narrative. In 2005, Chouinard published his memoirs with the revolutionary title Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman. In his book, he explained not only his own story of entrepreneurship, but his “work philosophy,” based on the teachings of his heroes: Muir, Thoreau and Emerson. He also emphasized the importance of employee welfare for achieving success in any project.

But perhaps most significantly, Chouinard contended that capitalism can turn its profits into initiatives that benefit the world. He went on to prove that point through his actions. In 2008, he appointed Rose Marcario, who is openly gay, the company’s CEO; in 2011, the company took out a full-page Black Friday ad in the New York Times featuring a photo of one of its trademark fleeces and a giant headline that read “Don’t buy this if you don’t need it”; in 2015, the company supported the launch of a platform to sell second-hand Patagonia clothing; in 2016, Patagonia donated all of its Black Friday profits ($10 million) to environmental organizations; in 2017, Chouinard denounced President Trump for removing protections from national park lands in Utah; in 2018, after saving money through a Republican-driven corporate tax cut, the company gave the money to groups committed to fighting climate change; in 2020, Patagonia stopped advertising on Facebook as part of the “Stop hate for profit” campaign; and in 2021, Chouinard donated $1 million to the activist group Black Votes Matter to help register black voters in Georgia.

Chouinard’s climbing adventures in all kinds of extreme conditions, his love of nature and his knowledge about the environment (he is one of the world’s leading experts in ice climbing) were all genuine. Why wouldn’t his declarations of environmentalist intent be real as well? Patagonia has proved adept at making masterful moves amid the raging culture wars. The company has won over many customers who consider themselves progressives, as well as those who see the Patagonia logo as a way to enter a secret society. The brand’s faint whiff of exclusivity appeals to veteran fashionistas who, in between wearing $2,000 heels and $12,000 coats, occasionally don Patagonia’s inexpensive caps as they leave Gucci or Dior fashion shows.

Of course, Patagonia and Chouinard also have detractors. For example, in 2011, the Atlantic reported that Patagonia was still finding instances of employee exploitation in its production chains, despite its diligent efforts to end sweatshop abuses. Perhaps when the company was just a group of friends who had opened the Ventura workshops, such things were easier to control; with suppliers in 16 different countries, the task is much more difficult. Chouinard has never claimed otherwise: after all, his principles are transparency and sincerity, not saintliness. In fact, the Atlantic article’s data came from one of Patagonia’s own public reports. Then, last Thursday, when news broke of the initiative to donate 100% of the company’s profits to environmental causes, the conservative National Review ran an article entitled “The Socialist Billionaire Who’s Getting a Sweet Tax Deal.” The magazine claimed that Chouinard is only donating the company’s profits because he wants to avoid paying millions of dollars in taxes. Surely, the businessman would not deny that this is an added benefit of his strategic decision.

In 2018, during his lecture at the Commonwealth Club of California, Chouinard unabashedly defended the practice of companies seeking to maximize their profits in the capitalist system. He noted that “the key is what you do with [the profits], whether you use them to do evil, like the [rightwing] Koch Brothers, or to do good.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.