How to create paradise: A tale of love, death and nature

Twenty-five years ago Douglas Tompkins and Kristine McDivitt Tompkins purchased thousands of hectares of land in Chile and Argentina and brought in expert help to restore the land to its pristine glory. The land is now being handed back to local governments. This is their dream come true in the heart of South America.

She has just finished gulping down half a chicken as if it were an appetizer and the main course is still to come. But first, she has to go to school to learn how to hunt. When the whistle blows and the cage door opens, Tobuna bursts out with feline speed towards the corral, where she follows the scent of entrails through the meadow. It smells like blood, but it will still take her a few seconds to find what’s left of the prey. Tobuna is the first female jaguar to be introduced in the region, where the other members of her species have become extinct. This reinsertion project is led by the Conservation Land Trust (CLT) organization in San Alonso, in the northeastern Argentinean province of Corrientes.

The project, located 700 kilometers north of Buenos Aires, is one of many that the CLT has launched in the Iberá Wetlands reserve, where, between 1997 and 2002, the organization bought up 150,000 hectares of private land. The CLT’s objective is to restore the zone’s original landscape and fauna before handing it back to the state of Argentina.

The story of San Alonso began 20 years ago in the Iberá Wetlands, the second-largest wetland reserve in the world. It holds 13,000 square kilometers of fresh water (slightly smaller than the state of Connecticut) and offers an array of landscapes – lakes, reservoirs, palm groves, meadows, forests – a natural paradise that rivals Florida’s Everglades. Here “silence” is written in green. It’s a place where you can contemplate the sunset over the Iberá Lagoon (Iberá means “waters that shine” in the local Guaraní language) while surrounded by crocodiles, monkeys, deer and wading birds that stand only a few meters away.

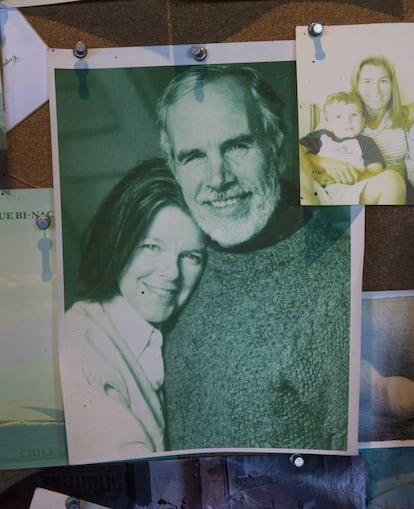

The CLT was founded by Douglas Tompkins, an American businessman who amassed millions of dollars through his clothing brands North Face and Esprit, and his wife, Kristine McDivitt Tompkins, former CEO of the Patagonia clothing company. Tompkins died in 2015 in a kayak accident in southern Chile.

The foundation is considered by many to be an inspirational ecological project. It recently won the BBVA Award for conservation and biodiversity work in Latin America and has attracted scientists and biologists from all over the world. Among them are four Spaniards who now call the region home. Besides helping and studying nature, they are also learning how to dance the chamamé, an accordion-fueled regional dance.

“It’s happy music, but with a deceptively slow rhythm, I still need to go to classes even though I’ve been practicing for the entire four years that I’ve been here,” says Jorge Peña Martínez, a veterinarian at the CLT, who worked at Madrid Zoo, before switching the conversation to the antibiotics he just gave to two tapirs in quarantine.

The idea of reintroducing jaguars had fascinated Tompkins since he bought a residence in San Alonso in the 1990s, but it wasn’t until 2013 that the project got going. Jaguars are the largest felines in America, only 200 are left in Argentina and their reintroduction into the wild is one of the CLT’s most complicated undertakings. It took two years and millions of dollars just to build the corrals. The actor Leonard DiCaprio, just one of the benefactors, donates $300,000 each year. Nearby towns see the return of jaguars as promising. A hotel named Tobuna Suites, after the hungry female, has just been opened in Concepción, one of the oldest towns in the province of Corrientes, with a population of 4,800.

With amber eyes and a powerful gait, Nahuel, the male jaguar, paces nervously from one extreme of the corral to the other, while he waits for his lunch. His routine is similar to Tobuna’s – he gets half a chicken for free and then he has to work for the rest to train his nose.

One phrase inspired everything Douglas Tompkins did: “That which is beautiful is good”

“They come here from zoos or rescue centers and have to relearn their habitats and how to make it on their own. If the female gets pregnant, she will have to teach her cubs how to hunt, and we won’t be in contact with her anymore. The felines conserve their instinct to stalk and kill, but today, when they trap an armadillo or a capybara [a type of rodent], they don’t know how to open them or eat them; that’s where we come in,” says Karina Spørring, an animal-behavior expert from Denmark, in charge of the jaguar project.

She decided to go to the CLT in Iberá because she heard they were doing something new. “I knew that there was a crazy guy from Valencia [Ignacio Jiménez Pérez, current head of conservation for the foundation] who worked with giant anteaters. So I came,” she says.

That was more than six years ago, she recalls, while she shows off the security cameras that they use to monitor the animals. Everything in San Alonso is powered by solar energy. Even the detergent is ecological and phosphate-free.

“Ms. Kris [McDivitt Tompkins] doesn’t allow us to bring in any other kind,” she adds.

The CLT has been working in Chile and Argentine for a quarter of a century and has created and expanded eight large protected areas covering a million hectares. These were brought from private sellers and returned to the two countries for public management.

“In Iberá we’re at this stage right now,” says Sofía Heinonen, a biologist from Buenos Aires who watched her two children, now adolescents, grow up in the wetlands. She currently presides over CLT Argentina.

“On November 6 we are going to hand the first of the areas, Cambyretá, over to the National Parks entity,” she says. The area’s 23,700 hectares will go from being managed by the NGO to the Argentinean state, as per Douglas Tompkins’ original wishes. His death did not change that. For the next decade the CLT will still maintain the right to manage the park’s wildlife, guaranteeing “the transition and backing” of the management model he created. The areas of San Alonso, San Marcos, San Nicolás and Carambola will follow suit.

The CLT’s objective is to have donated 150,000 hectares of land that will be converted into protected areas. It is ambitious and not limited to the flora and fauna. In both the Iberá Wetlands and in the organization’s projects in the Patagonia, it highlights the notion of “producing nature” to foster local human development. If other regions produce wheat or cars, the organization wants to learn how to produce deer, alligators and jaguars and let the region grow from there, thanks to ecotourism.

“What’s really exciting is to feel that every action is contributing to restoring a complete environment. A lot of what we do in these projects is being tried for the first time and could turn into a model for reintroducing species throughout Latin America,” explains Sebastián Di Martino, a biologist who has been working in national parks for 18 years and now coordinates the conservation and management of species throughout the Iberá reserve.

This project involves two distinct tasks. To restore the ecosystem, it is necessary to reintroduce animals that disappeared because of indiscriminate hunting or environmental changes. At the same time, animals that have lived in captivity need to be taught how to hunt, breed and live in the wild. Around 70 people are employed in these tasks in Iberá.

Another of the CLT’s reserves is the Estancia Rincón del Socorro. The nearest town is Colonia Carlos Pellegrini. With a population of around 700 and a network of dirt roads, it is where the Tompkins built a house.

“A large part of the economy is based on the strange-tailed tyrant,” explains Di Martino, referring to a tiny bird, with an orange beak and neck, whose long tail ends in two comically long black feathers. It is a bird-watcher’s dream.

“Yesterday the birds delighted a group of English tourists who were pleased to add the species to the list of rare birds that they’ve observed,” he says.

Anteaters were the first animals to be reintroduced into their natural environment by the CLT. Scientists released the first batch into the wild in 2007 and now they estimate that there are between 50 and 60 roaming freely in the area. Besides anteaters and jaguars, the NGO is also reintroducing tapirs, collared peccaries, red macaws and pampas deer into the reserves.

Mishky, a female anteater who came from a rescue center in Argentina’s Tucumán province, had half of her tail destroyed. Despite her troubled past, she now lives freely in the Rincón del Socorro, one of the organization’s five reserves in the Iberá Wetlands. We found her with her offspring clinging to her back, after tracking her through the sound of the radio transmitter that allows the scientists to monitor her. Sporting rubber boots, the scientists walk following the ‘beep’ that sounds like a heartbeat, navigating through yellow pastures (more reminiscent of the African savanna than the jungle), extremely careful not to step on snakes and hoping that the lingering black clouds don’t turn into rain. Eventually the anteater comes into sight, calm and curious. She approaches us and sticks out her tongue, thin and large, like a red thread that adds half a meter to her length.

“Move slowly,” advises Emanuel Galetto, a park ranger who is in charge of monitoring the reintroduced species. He keeps Mishky at a distance with a long stick that, every once in a while, he uses to scratch the animal’s back. And she appreciates every touch. Anteaters aren’t aggressive, he explains, but if they feel threatened, they can attack with claws that cut like knives.

“That’s why some neighbors shoot at them. When they are defending themselves, the anteaters will kill dogs and in return, they receive a bullet. Even so, people don’t dare kill the baby anteaters so they bring them to rescue centers and that’s how they come to us,” he says.

In Cambyretá, situated in the locality of San Ignacio, 25 minutes by airplane from San Alonso, there are different animals, but the zeal of the team is identical. It seems as though Noelia Volpe isn’t bothered by the fact that every cubic centimeter of air that surrounds her buzzes with the sounds of frenetic little wings belonging to every insect imaginable. She’s a biologist in her thirties from Buenos Aires. She is in charge of the macaw project and is working on her doctoral thesis about the reintroduction of this species that, in the past, had disappeared from the region. Volpe talks about the birds and their achievements affectionately.

“We train their muscles so they have resistance when they fly, because before they had only flown in zoos,” she explains. The bright-red, turquoise and green hurricane that weighs a total of 1,052 grams is called Gnocchi. She flies from one end of a training beam to the other with such a commotion that you can hardly hear the whistle that signals the beginning of the exercise. She knows that every time she completes the drill she gets the opportunity to stick her head in a trough and eat a ration of sunflower seeds – the ultimate delicacy in this aviary.

The CLT has been working in Chile and Argentine for 25 years and has created and expanded eight protected areas covering a million hectares

Douglas Tompkins, the successful businessman and environmental activist, was an admirer of the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess and his idea of “deep ecology,” which considers all beings (including humans) to be equal. Tompkins was also a lover of nature and extreme sports. He fell in love with the Patagonia region in the 1970s – climbing the 3,405m of Monte Fitz Roy in the Andes mountain range, two decades before El Chaltén, Argentina’s youngest town, was founded, and when there was nothing more than wind, ice and adrenaline.

His eventual establishment in the south of Chile, 25 years ago, was accompanied by suspicion, criticism and controversy. Locals accused the “gringos” (a name which some in Iberá continue to use for the couple) of wanting to keep the thousands of hectares of land for themselves and of attacking progress and local production. The Tompkins’ declared intention to return the land to the government after restoring it to its original glory, sounded too good to be true.

“Doug Tompkins always said that people judged him without paying attention to the tradition, which is common in the United States, of simply donating money to causes that one cares about. The idea of legacy was essential for him,” explains Heinonen, the biologist, as she drives through Rincón del Socorro in an off-road truck (the only kind of vehicle capable of cutting through the muddy terrain when it rains). As if we were stopping at a regular highway tollbooth, we come to a halt to allow a dozen of the world’s largest rodents – capybaras, weighing up to 50 kilos – continue following their path. We give way to other animals too, such as rheas (ostrich-like walking birds) and a native deer species.

Without responding to any of the local criticism, the Tompkins invested $450 million, most of it on land, over 25 years in Chile and Argentina. Now, the international awareness of Doug Tompkins’ tragic death has seen the dawning of a new era. “It’s as if after his absence the locals have reevaluated their opinion, realizing that he didn’t want to ‘steal Iberá’s water,’ but instead to create a new model for conservation,” says Heinonen.

Although more than a year has passed since his death, the people in Rincón del Socorro, where he lived six months out of every year, speak fondly of him. He is remembered above all for his perfectionism, the daily flights that he took in private plane over the lands, his respect for the authentic and for a phrase that inspired everything he did: “That which is beautiful is good.”

English version by Alyssa McMurtry.