‘Kids’: The indie movie sensation with a darker side

The film was a hit when it was released in 1995, but 27 years later, another story has been told: that of the young and inexperienced actors who were pushed into the abyss

In 1995, Justin Pierce skated through the streets of Manhattan with only two worries: finding a place to sleep and something to eat. Just one year later, he picked up the Independent Spirit Award for best acting debut in the film Kids. And, five years after that, he was found hanging in the Bellagio Hotel in Las Vegas.

Harold Hunter, one of Pierce’s co-actors, had a similarly tragic life. At the age of 20, he was the leader of a gang: the Washington Square Skaters. Living in public housing and addicted to drugs and alcohol, half of his family members had been victims of the crack epidemic that devastated New York City in the 1980s. By the age of 21 he was rubbing elbows with Leonardo DiCaprio… and 11 years later, he would be dead from a cocaine overdose.

Hunter had introduced Harmony Korine, a film student, to his skater gang. Inspired by the daily lives of Pierce, Hunter and their friends, Korine wrote the screenplay for Kids, a movie about a day in the life of Telly – a 17-year-old boy obsessed with deflowering girls – and his gang, a group of boys and girls with dysfunctional lives who spend their days getting high, having sex, fighting and rolling around on their skateboards.

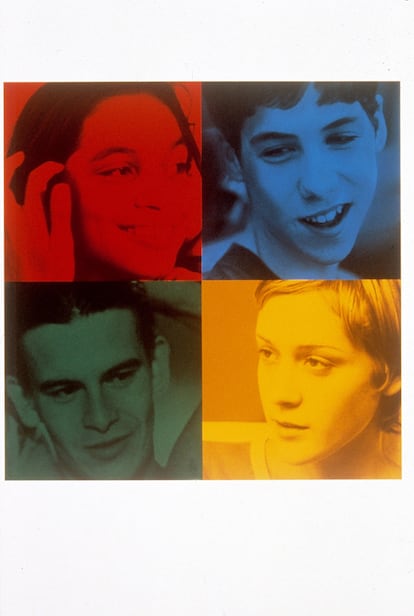

Kids became the most talked-about movie of 1995. “It’s Lord of the Flies with skateboards, nitrous oxide and hip-hop,” wrote The New York Times. Filmed like a documentary, it cost just over $1 million and grossed more than $20 million. Backed by the notorious Harvey Weinstein – who was delighted with any work that guaranteed controversy – it catapulted the careers of Chloë Sevigny and Rosario Dawson.

In 2021, Hamilton Harris – one of the boys featured in the film – participated in a documentary titled We were once kids, directed by Eddie Martin. Harris pursued this project after becoming alarmed when he discovered that a large part of the movie’s viewership mistakenly believed that they were watching a documentary.

“My feelings towards the movie started to change after seeing the global reaction it got,” he told Variety. At the same time, he felt that the creators outside the group – Korine and director Larry Clark – failed to capture the strong sense of community that the teenagers had created. While the film reduced the existence of its protagonists to a devastating nihilism, the truth is that those kids – who used skateboarding as an outlet – had formed a family. They were protecting each other, escaping from homes where drug usage and violence were common. Carefree sex was not at the center of their lives: in fact, many of the protagonists were virgins.

Harris also wanted the documentary to honor Pierce and Hunter, two victims of a phenomenon that, in his opinion, used and abandoned them.

“You can take a person out of the ghetto, but you can’t take the ghetto out of a person… to me, ghetto refers to the mental and emotional trauma we went through.”

Pierce, Hunter and Harris grew up in the New York of the 1980s, a city devastated by crack and insecurity (it was still a few years before Disney and 1990s mayor Rudy Giuliani would turn it into a tourist paradise). They found their refuge in skateboards that they built piece by piece.

“White, Black, Chinese. All different and all skating together,” recalls Harris in the documentary. Their skater gang – which had members between the ages of 12 and 20 – coordinated everything, even how to feed itself. Some were assigned to steal bread; others stole sausage

The life of the gang that brimmed with camaraderie but had a bleak future changed when a guy started hanging around the park. Fifty years old, greasy hair gathered in a ponytail, wide pants and plaid shirts, he carried a camera. ”Who is that geezer?” they wondered. He was friends with Harmony Korine and supposedly “a famous photographer.” This was Larry Clark: his book, Tulsa, a collection of portraits of heroin addicts in his native Oklahoma, had made him one of the star artists of the subversive movement. In exchange for their stories, Clark provided the boys with an open bar of quality alcohol and marijuana.

None of the skaters took the movie Clark claimed to be preparing too seriously – that is, until casting announcements were plastered on the walls of the East Side. Both the director and Korine insisted that the actors not be professionals. The first to join the project was Pierce (the role of Casper was written specifically with him in mind).

The problematic part came with the female roles. When the women in the gang read the script, they refused to participate. It did not reflect the relationship of camaraderie that united them: it was simply a festival of sex and drugs, a film “about rape and misogyny” says Priscilla Forsyth, who ended up participating in a minor role with only one sentence for posterity (“I’ve fucked and I love to fuck”). On the other hand, the boys could be of non-normative beauty, but the girls chosen to star in the film included 15-year-old Rosario Dawson – whom Korine discovered in a social housing project where she lived with her grandmother – and Chlöe Sevigny, a New York club regular who, after being featured in two fashion editorials and a Sonic Youth video, had become the city’s great underground sensation.

The script – as the girls in the gang predicted – portrayed the youth as a group of zombies eager for sex and drugs. But it didn’t matter: someone noticed them and offered them a way out. “It’s my escape!” Hunter yelled when he was cast in the film. Clark gave them $1,000 each and made them sign some papers. Despite being minors, none of them had adult advisers.

Kids went to Sundance and became the sensation of the festival. The children who appeared onscreen had no idea, but behind that amateur-looking work were the names of Gus Van Sant – the producer behind every indie hit – and the almighty Harvey Weinstein. The Miramax tycoon paid $24 million to distribute the movie.

After the screening at Sundance, critic Emanuel Levy wrote: “With its bold and frank approach, Kids dwarfs all Hollywood teen movies, pushing new boundaries in its portrayal of sex, drugs and leisure.”

It premiered in more than a hundred theaters in the United States; the lines stretched around the streets of New York City. Suddenly, the group of misplaced teenagers were the most famous people in town. Newsweek called the film “a wake-up call.” The climax came with its premiere in Cannes: in a very uncomfortable press conference, both Clark and Korine said that none of the film’s protagonists had used drugs during filming.

This statement is debunked in We were once kids. In the documentary, you can see the youngest actor in the film, a 12-year-old, smoking marijuana.

“In one sequence, we smoked 10 joints in a row,” says Javier Nuñez. He was one of the protagonists of the devastating final sequence, a rape scene that was shot with Nuñez asleep next to the action: “I was a child, I just fell asleep,” the actor now acknowledges.

From Washington Square, the protagonists contemplated the success of the film in astonishment. None of them were on a boat in sunny Cannes – the $1,000 had already evaporated. Someone else was making a lot of money off the doctored story of their lives.

There was, however, a bit of good news. The Spirit Awards crowned Justin Pierce as the best newcomer of the year. Harold Hunter went with him to receive the award. The offers began to arrive and both moved to Los Angeles. They quickly became the new celebrities who dazzled the old celebrities. Leonardo DiCaprio invited Hunter to his parties; David Letterman invited Pierce to his show. The money flowed in – at least for Pierce. He acted in Ice Cube’s film Friday and in a couple of episodes of the sitcom Malcolm in the middle. But Harold’s phone stopped ringing. He took refuge in whiskey and cocaine to overcome feelings of failure.

Pierce also went through erratic times, often travelling to New York to see his friends. He married the stylist Gina Rizzo and seemed ready to start the family he never had… but when his wife suffered a miscarriage, he fell apart. He committed suicide in a Las Vegas hotel in 2000.

Six years later, Hunter passed away from a heart attack stemming from an overdose. He was never able to recover from the emotional impact of feeling like a star, while still having to live in public housing. He died in the same neighborhood where he was born.

The director of We were once kids does not point to a culprit, but hints that many powerful people made a fortune while the protagonists were exposed to the world with their allegedly amoral lifestyle. Clark and Korine never passed through the neighborhood again… but the Washington Square skaters were still there.

“People like Pierce and Hunter lacked the support networks necessary to navigate the Hollywood scene,” he stressed in Variety. “Many of them were runaways or people from traumatic backgrounds or troubled homes. They were very trusting of the filmmakers and gave a lot. And then they didn’t have anyone around to help them or give them guidance while there was a narrow window of opportunity that opened for them.”

There were those who did manage to seize the moment. Both Rosario Dawson and Chlöe Sevigny became stars. And Leo Fitzpatrick (who gave life to Telly, “the surgeon of virgins”) continued to play small roles in series such as The wire. Clark continued to shock audiences with films like Bully or Ken Park. Korine became an enfant terrible of the counterculture, thanks to unclassifiable works such as Gummo or Trash Humpers. None of these individuals appear in the documentary, as it has opted to just give voice to those who did not have one 27 years ago.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.