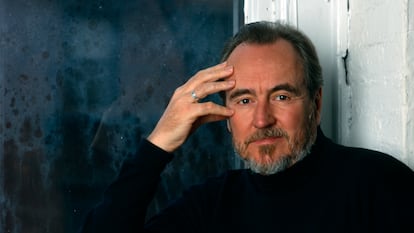

Wes Craven, the master of horror who wanted to direct dramas

A new biography of the director of ‘A Nightmare on Elm Street’ and ‘Scream’ reveals the secrets of the man who scared the whole world

Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman had copies of movies such as Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor and The Blues Brothers comedy in his private video library on Fårö island. But there is no evidence that he ever watched the adaptation a US director dared to make of his classic movie The Virgin Spring (1960). Called The House on the Left, this movie turned his award-winning film into a documentary-style horror show, filled with cruelty, mutilations and visceral scenes of violence. The movie – with its overly pornographic script – sparked protests in cinemas, with spectators rioting to destroy the movie reel. Some members of the public fainted while watching it, while others vomited. “People wouldn’t leave me alone with children. And once I was at a dinner where I was introduced to a woman sitting next to me. When she heard my name she left the table and went home,” the director would later say in an interview. That name was Wes Craven.

The uproar over The House on the Left is the starting point for Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares, a biography of the US filmmaker behind legendary horror films such as Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and Scream (1996). Written by John Wooley, a journalist who specializes in pop culture, the book was originally published in 2011 and has now been released in Spanish. Craven, who died in 2015, even collaborated with the biography.

“He was very accommodating when I interviewed him. I have no idea how he felt about the book, though he comes off very well in it,” Wooley tells EL PAÍS. The book explores Craven’s frustration at being dismissed by the critics just because his movies were of the horror genre. " With the rise of what’s been called the ‘nerd culture,’ comic books and horror movies have achieved a kind of respectability. I think Craven was very serious about what he did, and he did the best job he could and became an innovator as well,” says Wooley.

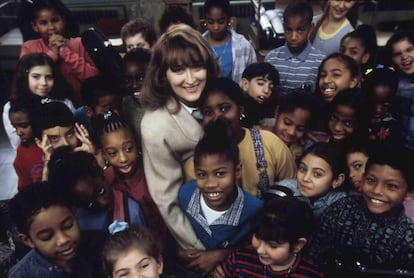

But Wes Craven didn’t want to make horror films; he wanted to make dramas, according to the biography. He was able to do this in 1990, when he directed Music of the Heart, a coming-of-age story based on true events, which won actress Meryl Streep an Oscar nomination. But he was only given the chance to make the movie by agreeing to direct more films in the Scream saga for the production company Miramax. Wooley’s book explores how Craven was typecast as a director: when making the sci-fi movie Deadly Friend, he was asked to put in bloody scenes to make it more “Wes Craven” – even if they didn’t fit with the plot. But Craven, who Wooley calls “an artist who plied his art in the medium that was available to him,” was able to develop a style that met his criteria and also pleased his producers and fans, one that fused art with horror exploitation.

Born in 1939 in Cleveland, Ohio, to a strict baptist family, Craven grew up knowing nothing of the horror genre because he was never allowed to watch horror movies – an ironic start for the man William Friedkin, the director of The Exorcism called “the best horror director in history.” But that would soon change. Craven became passionate about the new European films that were hitting theaters with growing frequency. So he decided to resign from his position as a college professor in Clarkson, New York, where he taught modern theater, art and literature, and try his luck in the world of the cinema. In his search for work opportunities, he teamed up with Sean S. Cunningham (who would go on to make the Friday the 13th saga) to get a job in the fledgling soft porn industry, until they hit upon a formula to win over teenagers: mix porn with horror. “I told Cunningham that I didn’t know how to make horror movies and he told me to look for the skeletons in my closet,” Craven recalled in an interview for the documentary series Bergman’s Video (2012), where well-known directors described the influence of the Swedish filmmaker on their careers.

Breaking barriers

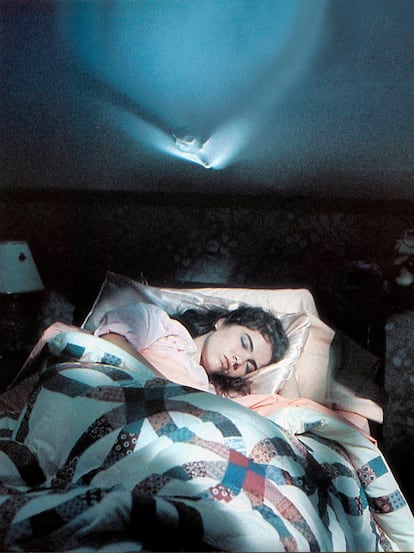

“My film made the director of The Last House on the Left leave the room!” Director Quentin Tarantino has often mentioned, not without a note of triumph, that Craven walked out of Reservoir Dogs at Spain’s Sitges Film Festival. “He was repelled by real violence and Tarantino’s treatment of violence did not suit him. If you think about Nightmare on Elm Street, its violence is still fanciful, it is shocking because what you see is not possible,” José Mellinas, the Spanish translator of Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares tells EL PAÍS. “He is the erudite figure of horror cinema. In his films, you can see a more cerebral, mental approach, a more Freudian game between dream and reality. That’s Craven’s hallmark.”

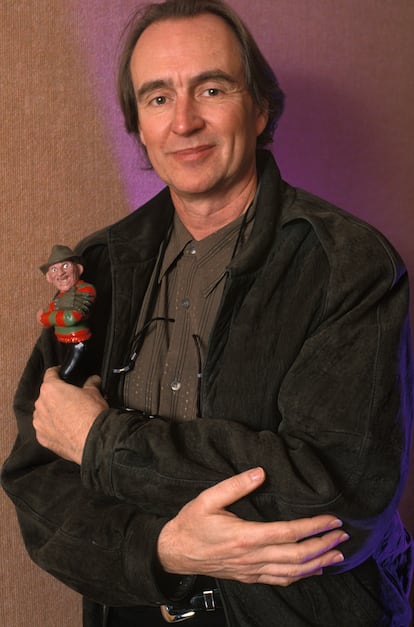

The Nightmare on Elm Street franchise was so popular that according to a 1989 survey, the movie’s villain, Freddy Krueger, was twice as famous as Abraham Lincoln among children.

“Wes Craven revolutionized horror three times in three different decades, with The Last House on the Left in the 1970s, A Nightmare on Elm Street in the 1980s, and Scream in the 1990s. It would be incredible if you could do this just once in your life,” says Mellinas. For Wooley, the director’s cinematographic style stands out for its “self-referential approach, and taking the dreams-vs.-reality idea to new levels.” According to Wooley, this style reached “its peak” in Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994), the seventh installment in the Nightmare on Elm Street saga. In it, Freddy Krueger chases the lead actress from the first film, Heather Langenkamp (playing herself), after Wes Craven and producer Robert Shaye (also playing themselves) pitch a new sequel.

This breaking of the fourth wall is considered the prelude to Scream, which at the time was the highest-grossing slasher movie in the world. Scream 3 (2000), which was produced by convicted sex offender Harvey Weinstein, discusses sexual abuse in the movie industry. “I wish I could speak to that, but I honestly don’t know. Seems to me it would have to be more than coincidence,” says Wooley, when asked if Craven could have been alluding to Weinstein.

Both Wooley and Mellinas say that Wes Craven has left his mark on fantasy and horror cinema. Matrix Resurrections (2021), for example, follows a similar metanarrative to Scream 4, while the Netflix show Stranger Things has put Nightmare on Elm Street on the radar – the series not only explicitly mentions the movie and includes an appearance of Robert Englund, the actor who played Freddy Krueger, it also uses Craven’s distinctive mix of dream and reality. “He was always interested in what young people thought, he adapted to new tools and language. In Scream 4, he tried to speak of that modern language,” says Mellinas.

Meanwhile, Jordan Peele – one of the great names of contemporary horror who is praised for using the genre to discuss complex issues, such as racism – is set to remake Craven’s movie The People Under the Stairs (1991). What would Craven have thought of Peele? It’s a question that cannot be answered. Just as we will never know what Bergman would have thought of The Last House to the Left.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.